The production growth in the Permian Basin has created a new dilemma for operators looking for cost efficiency. In September Bloomberg predicted that Permian production could rise from its present level of 2.4 million BOPD to 10 million BOPD, a rate that could produce up to 50 million B/D of flowback water. With the WTI price at around $57/bbl in early December, disposal of that flowback water can be expensive. Bloomberg estimated the cost of the service is between $1.50 to $2.50/bbl.

While this predicted spike in water volume may be an issue for operators, it is an opportunity for oilfield water management companies working in the region. With demand for their services going up, these companies have already begun acquiring pipeline infrastructure, saltwater disposal (SWD) wells, and facilities.

Multi-Basin Strategy

With water management becoming a critical issue for operators in the Permian, midstream companies have been aggressive with mergers and acquisitions in their efforts to bolster their positions. H2O Midstream’s acquisition of Encana’s produced-water-gathering system last June gave it control of more than 100 miles of interconnected pipeline and five SWD wells with a total permitted disposal capacity of 80,000 BWPD. In September 2017, RRIG Water Solutions announced the acquisition of a 475-mile pipeline from Oilfield Water Logistics. Located in the eastern part of the Delaware Basin, the pipeline has the potential to move more than 2.3 million B/D of fresh water.

WaterBridge Resources is another company that has been active in the Permian region. Since its founding in 2015, the midstream development company has focused on acquiring and operating flowback and produced water infrastructure for various oil and gas producers, including water sourcing, gathering, reuse, pipeline infrastructure, and disposal infrastructure.

In August 2017, WaterBridge acquired EnWater Solutions, a company whose current assets include more than 100 miles of gathering line and nearly 150,000 B/D of permitted disposal capacity. WaterBridge plans to extend EnWater’s existing gathering business into a full-cycle, closed-loop water system, and by the end of 2018 the company expects to have more than 300,000 B/D of disposal capacity and 200 miles of interconnected gathering pipe.

“The assets we acquired from EnWater are located in the southern Delaware, and the EnWater team’s expertise encompasses the entire Permian region from the Delaware to the Midland, so that was a regional platform with an existing management team that we acquired,” WaterBridge founder and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Steve Johnson said.

Johnson said that although WaterBridge has no direct investment in recycling technology, it has alliances with several large companies that specialize in recycling. The EnWater acquisition, and WaterBridge’s subsequent acquisition of Arkoma Water Resources in Oklahoma’s Arkoma Basin, are part of the company’s strategy to expand its operating presence into multiple basins while maintaining a core focus in the Permian Basin. Johnson said the multi-basin strategy is a case of “going where the water is.” Handling greater volumes in different areas could make it more valuable to operators who may also look to expand their presence into other basins.

“As an entity, we’re focused more on our customers than we are on geography,” he said. “Having said that, there are certain areas across the US where the water/oil ratio is much greater. The Eagle Ford is fairly dry, the SCOOP/STACK is fairly wet, and the Permian’s fairly wet. The water/oil ratios are what we chase because, at the end of the day, our business is a volumetric business. The greater the volumes of water to be handled, the better our profitability is.”

WaterBridge President and Chief Operating Officer John Durand said the multi-basin strategy is similar to his experience working with other midstream companies during his career. Prior to joining WaterBridge, he served on the management team at Pioneer Water Management and has midstream experience working in the Delaware and Midland Basins, as well as other shale plays across North America.

“After the Barnett Shale first heated up in north Texas in 2002, you saw operators later migrate to the Eagle Ford and subsequently into the Marcellus and the Utica. As a result, many of the same operators who were our customers in Texas ultimately pulled us along to provide midstream services in the newer shale plays outside of Texas.”

While Durand’s experience in those shale plays came when he worked for previous midstream entities, he said he believes the same dynamic will hold true for WaterBridge.

“We are customer- and relationship-focused and we believe that when you do a good job with an operator in one basin, they will naturally want to bring you along to execute projects in other areas on their behalf,” Durand said.

Midland Basin Operations

In December 2016, Solaris merged the operations of Water Midstream Partners (WMP) into a subsidiary, Solaris Water Midstream. Solaris CEO Bill Zartler and Chief Financial Officer Chris Work said that the WMP merger offered several opportunities in the Midland Basin. Both companies had footprints in Midland County: WMP had an SWD well connected to two other third-party wells, along with more than 35 miles of commercial saltwater-gathering pipelines serving multiple operators in Midland, Howard, Martin, and Dawson counties, while Solaris was drilling an SWD well approximately 10 miles away from WMP’s SWD well.

By connecting the two wells, Solaris now has a water management system with the two SWD wells and high-capacity deep injection wells in the Ellenburger formation. Zartler said the multioperator, multi-SWD well system has become the base for its recycling business.

“We were in the process of finishing a well with pipelines to multiple producers. Some of those were the same and some were different. We’ve connected those two wells into the system and now we have a very robust gathering network, disposal well network—both ours and third-party—and the ability to send that water back to permanent pipe for recycling.”

Work said the company also has a permit for a third Ellenburger well and the potential to add a fourth well in that system. In addition, he said Solaris has added new operators to the system that were not contracted to either it or WMP at the time of the merger.

“It’s the kind of thing that you like to see in a merger where you get more efficiencies,” he said. “They’re a company with a little more capabilities. We have a little more money that we can bring to bear. They had operational people and assets. We were just getting going on some greenfield projects. We were able to put all of those together in a matter of 10–11 months, and we also added the recycling capability there that really wasn’t something either one of us were doing.”

Solaris first began work on the recycling project since the first quarter of 2017. Zartler said the company had previously been loath to embark on what he called a “massive” technology leap needed to bring the project to fruition, but that the investment has been worthwhile.

Permian Infrastructure Trends

The recycling project is part of Solaris’ efforts to take advantage of trends it had identified with produced water management. The first trend is that water handling is turning into what Zartler termed a “true infrastructure business” where operators develop more permanent infrastructure, instead of relying on temporary solutions such as trucks, to haul away the volumes of produced water coming from Permian wells. Zartler said operators are starting to outsource the construction of this infrastructure to other companies, and this outsourcing should increase as the public markets focus on capital returns instead of lease operating expenses (LOE).

Johnson said that getting operators to understand the need for outsourcing water management has been one of the greatest challenges for midstream companies working in the area.

“Operators tend to want to have a lot of control. However, they first have to weigh their desire to maintain control vs. their preference to spend capital more wisely. By focusing on the drill bit vs. committing large amounts of capital to lower-return midstream infrastructure projects, operators will come out ahead. So the first step is to have the operator provide their drilling and completion development plan, followed by a definition of the customized midstream water infrastructure project they want us to build to suit their needs,” Durand said.

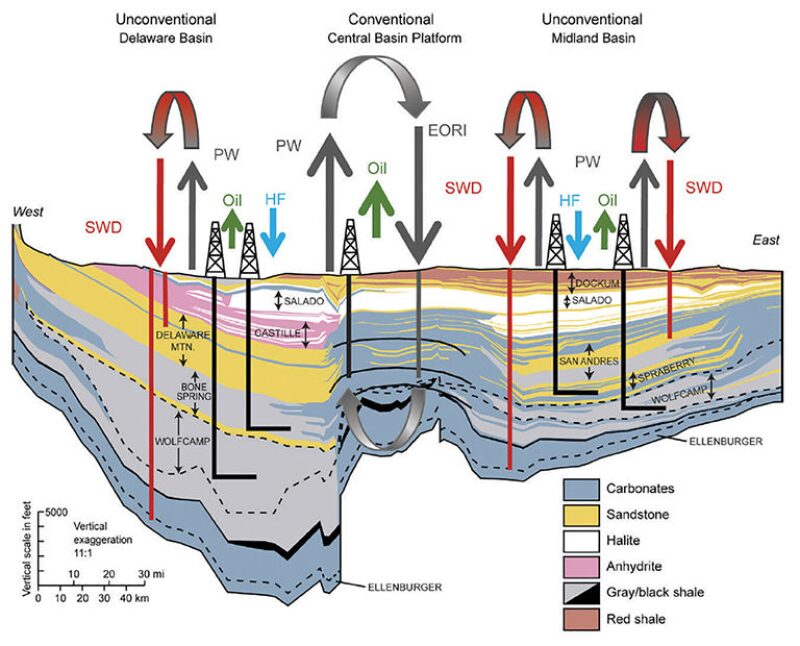

Another trend Zartler identified is that the economics of disposal are becoming more difficult, thus furthering the need for more produced water infrastructure. Fig. 1 is a cross section of formation depths along the southern margin of the Permian. Zartler said that parts of the Midland Basin have seen higher volumes of water being injected into shallower zones in recent years, making the deeper Ellenburger formation a prime location for future SWD well construction. Deeper SWD wells, he said, will require larger capital investment.

“You’re drilling a well that costs three times as much as the old mom-and-pop saltwater disposal well that was all trucked in,” Zartler said. “You’re getting infrastructure in place to handle this water via pipe vs. just the truck business.”

Work said the levels of drilling activity in various parts of the Permian have dictated the amount of water handling infrastructure already in place. He noted a greater level of vertical drilling in the Spraberry sandstones of the Midland, necessitating more infrastructure than what is currently in place in the Delaware. In addition, the wells in the Delaware are bigger, meaning that any future infrastructure that will be built there will be larger than in the Midland.

While wells in the Midland are typically 4 to 10 in. in diameter, Work said that Solaris’ wells in the Delaware may range from 12 to 20 in. He said the company is planning to recycle hundreds of thousands of barrels of water per day and will also develop large-scale pits to store it.

“The scale of the infrastructure is going to be larger. The systems are going to be larger. We’re talking about hundreds of miles of large-diameter pipe covering multiple operators. It really looks a lot more like what you see on the midstream side where you have very-large-diameter pipe covering pretty good distances with multiple operators. Out in the Delaware they’re starting to do the pad drilling too, so it’s really going to explode in 2018 from the numbers that we’re seeing,” Work said.

Recycling vs. Disposal

Johnson said the economics of produced water recycling vs. the use of SWDs is a function of commodity price. The higher the prices of oil and gas, the more options operators have to dispose of their produced water. While regulatory issues with produced water disposal put additional pressures on operators, he said that the commodity price will be the ultimate indicator of whether recycling efforts will increase in the Permian.

“At the end of the day, it all comes down to LOE as a percentage of commodity price. As one grows, the other has to grow, or else there’s increased tension on profitability for the operators who ultimately pay all the bills,” he said.

Durand and Johnson also agreed that trucking was not a feasible long-term solution for handling the volumes of produced water in the Permian. Durand said that moving forward, pipelines will be the optimal means of transport.

“Given the size and number of the completions today, the sheer volume of water required, it is just not feasible to have trucks on the road,” Durand said. “Nobody, from the E&P operator to the local municipalities to the residents of those communities, wants trucks on the road. Even with limited trucks currently moving less water than before, there is still too much truck traffic. By moving water through permanent underground pipelines, you’re moving it more cost-effectively and certainly more safely than you would by moving water by truck.”

For Further Reading

Scanlon, B.R., Reedy, R.C., et al. 2017. Water Issues Related to Transitioning from Conventional to Unconventional Oil Production in the Permian Basin. Environ. Sci. Technol 51(8): 10903–10912. (accessed 29 November 2017).

Wethe, D. and Collins, R. 2017. Forget Oil, Water is the New Ticket for Pipeline Growth in Texas. Bloomberg, 14 September. (accessed 29 November 2017).