Behind every driller drilling a horizontal well is a directional driller. And increasingly, there is a screen in front of the driller showing what to do next.

“It is like a navigation system for drilling,” said Ginger Hildebrand, operational efficiency manager for North America land drilling at Schlumberger. Based on surface and downhole data, it delivers “step-by-step directions, shows you where you are and how well you are performing.”

In other words, the directional drilling advisory software (directional advisor) is designed to do what a directional driller does for a living.

The goal of algorithm-driven decision making is to “industrialize directional drilling operations.” That means more consistent, efficient drilling, as measured by the time it takes, the ability to consistently deliver complex well designs, the quality of the borehole, and facilitating decisions that determine the long-term value of the well.

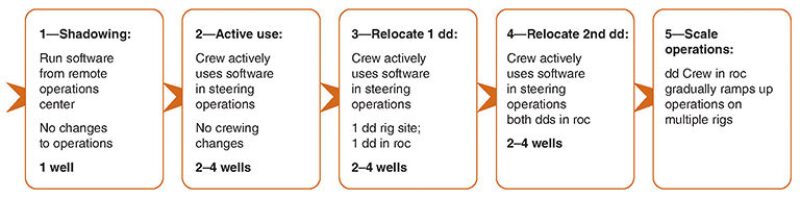

That quote came from a recent paper, Transitioning the Directional Driller Off the Rig (SPE/IADC 184682). It told how Precision Drilling managed to reduce, or eliminate, directional drillers on rigs by using a computerized drilling advisory system developed by Schlumberger and Pason Systems, which developed and runs the data network. Reliable communications are critical for new systems that connect teams of people, sometimes with directional drillers remotely monitoring the work.

Schlumberger and Pason have a system on the market as does Motive Drilling Technologies, a pioneer in the field that was recently bought by Helmerich & Payne. Tesco, which makes drilling tools, is developing an advisor as part of its Automated Rig Control system, and a startup, xnDrilling, is trialing one that uses drill path location information from Hawkeye Directional software.

The addition of a directional advisor on a drilling rig raises an unanswered question about what directional drillers will do. One possibility is working at a console in a remote center tracking a handful of drilling projects in progress using directional advisors. The idea of removing a key member of the rig team, though, has run into opposition.

“The biggest challenge … is getting directional drillers to buy into” a system that fundamentally changes their job, said Todd Benson, president and chief executive officer of Motive. Those resisting the change “see it reducing their job security or a devaluation of what they do.”

It also changes the systems used to manage drilling, and some operators have objected to losing these experienced leaders. “This changes how work is done; that to me is a big resistance point,” said John de Wardt, president of De Wardt and Company and one of the leaders of a group mapping the future of drilling automation. But he added, “This is going to happen more rapidly than people believe.”

Drilling Exposed

Even if the staff remains unchanged, the directional drilling job is changed when a digital directional advisor appears on the driller’s screen, presenting advice based on algorithms that determine when and how long to drill ahead and when to slide—turning the curved mud motor and drill-bit assembly to change direction.

The calculation used for every sliding and drilling section is done consistently, the results are calculated, and a record is saved, said Hildebrand, who led the team that developed the Schlumberger directional advisor called abbl (pronounced “able”).

The program driving the directional advisor consistently applies the well parameters and adjusts its calculations to reflect the results of previous moves. The directions from the directional advisor ensure more consistency in how directional drillers interpret a project’s priorities and the drilling& performance.

A directional driller can ignore the advice of the directional advisor. When that happens it will be apparent to everyone monitoring the well who will see “the deviation between what was recommended and what was executed,” said Ariel Torre, senior vice president of Integrated Drilling Services for Precision, adding that feedback that took hours or days “is in front of you as it is happening.”

“At Precision, with a million-and-a-half feet drilled, we have not had a case where the system was wrong yet,” Torre said.

Increasingly, decisions by directional drillers are converging with the calls of the directional advisor, he said.

Which is not to say the digital advice is the best possible move. Advisor-makers are constantly updating their software as they find ways to make the interfaces and the underlying algorithms more effective.

Those who worked on the Precision project had to adjust their approach as they realized the level of resistance was far greater than expected. “We understood very quickly it is a huge change management project. We are working toward it,” Torre said.

The directional advisors are being introduced at a time when directional drillers already have been battered by the industry slump. Their numbers began to decline with the rig count in 2014. While the rig count has nearly doubled over the past year, it is still less than half of what it was at the peak of the boom.

Even at that level, there are concerns about the supply of experienced directional drillers.

“There has been measurable attrition. There are some older ones who retired and are not coming back,” said Jim Oberkircher, executive director of the International Association of Directional Drilling. The daily wage for those 12-hour shifts lost a significant digit, going from around USD 1,700 a day to around USD 700 a day, he said.

As drilling activity increases, those doing the hiring have the difficult task of figuring out who to trust with meeting clients’ high expectations. Generally, directional drillers are consultants, often hired through smaller directional drilling companies that make up 80% of that sector.

“It is hard to determine who is a good directional driller aside from your own personnel experience,” Oberkircher said, adding, “There is a large degree of variation from one to another. You can tell differences ... from the day shift to night shift guy. It is measurable.”

Operating Decisions

The loudest voices in the directional drilling automation discussion are the oil and gas companies paying for the rigs. And they are focused on finding a way to turn a profit with oil prices down.

“The customers are operators. They do not want automation; they want a better well, a cheaper well, and they could not care less at the end of the day” whether new technology was used, said Lars Olesen, vice president for product line management for Pason.

While Benson has worked with companies that have moved directional drillers into remote operating centers where they can monitor the progress of multiple wells at once, there is no consensus on what change, if any, is needed to better manage directional drilling.

Robert Wylie, president and chief executive of xnDrilling, a company started to deliver drilling automation applications, recalled when the representative of a big oil company told him there was “no way she was going to pull her most experienced person off that rig.”

Another employee of a big oil company, though, told him they want to move directional drillers off their rigs.

Others in the business have gotten similarly mixed messages and are developing products that might be used in either case.

“There are many operators in this market with different priorities and values,” Hildebrand said, adding that their “directional advisor software can support all of those priorities.”

“I wouldn’t call it a trend yet (but) there is more than a little interest in it,” Oberkircher said.

For now, it is clear the directional advisors work as promised, but the industry lacks an example of how the directional advisor can be used in a way that delivers the level of performance improvement that a company might want to play up in an investor presentation.

When Precision drilled wells with no directional drillers on site, it took about the same amount of time as ones drilled with them on the rig. A directional driller monitoring multiple wells will reduce the day rate per well, but it is not a big saving compared with the total daily cost of drilling. Over 20 wells, a directional advisor should deliver more consistent results than a directional driller, but few companies announce when they have achieved major reductions in drilling time variance.

But the search is just beginning. The uniformity of digital drilling decision making could aid those looking for ways to test if other incremental changes produce measurable improvements. Otherwise those gains could be obscured by differences in how directional drillers work, Benson said.

Also, computers with fast processing speeds are needed to keep up with the pace of more complex well designs that spread out from well pads and then go 10,000 ft or more.

Change will require drillers and operators to lead by example by talking about successful efforts to change how directional drilling is done. The Precision project on reducing directional drilling staffing is an example of that.

While Motive will continue to sell its advisor to all directional drillers and operators, regardless of the drilling company used, it may benefit from being owned by Helmerich & Payne, which is known for innovations that improve drilling efficiency. “They will be partners to demonstrate and evaluate ways to make the most of the partnership” between computers and drilling teams, Benson said.

Others in the drilling business are following the leaders.

“Over the past 5 years, during the downturn, the drillers who were up and running first were the ones with rigs that had the latest technology. They absolutely included the latest software improvements,” said Doug Greening, vice president of research and engineering at Tesco.

Its ARC line of products began with devices to automatically control torque, which is a relatively easy sell because it can reduce the risk of problems everyone wants to avoid such as drill bit damage when they stick and then slip. It is working now on a directional drilling advisor called ARCGuide.

“If we didn’t set up and start producing these products for other drilling contractors, they could not keep up with the industry.” Greening said.

Fast Machines

The pace of drilling longer, more complex wells offers an argument for bringing in the power of a computer to guide directional drilling.

“The speed of drilling is so fast they cannot keep up with the calculations,” Benson said. To keep up, drillers need to do math on the fly and may have to resort to gut decisions. “For a directional driller with 2 years of experience that is never a good idea. An experienced directional driller can do better, but will still struggle,” he said.

The process of steering a drill bit is anything but intuitive. The drill bit, which is powered by a mud motor, is at the front of curved housing. When the drillstring is turned to slide, it changes direction but the reaction is not nearly as predictable as turning a steering wheel.

“It is like driving a bus, but you are not (steering) in the front, you are in the back. And the driver doesn’t get to see where he is until he gets there,” Torre said.

The process requires constant calculations to make predictions about where a slide will take it, and then checking downhole measurements to see where it went. Comparing the expected to the actual makes it possible to adjust future calculations based on how that equipment is performing. “People learn empirically what you are able to get in practice,” Hildebrand said.

A computer’s advantage is its ability to do calculations needed for an adjustment in seconds that would take minutes for a directional driller, allowing more and smaller course corrections, Greening said.

The goal is to balance following the line in the well plan with staying within the tunnel—the area that limits how far the drill path can stray from the plan. Sometimes if a client wants to prioritize speed, a larger tunnel is allowed, Torre said.

But that strategy may not survive if directional advisors proliferate. “One widely accepted approach is to ‘use the whole window,’” said Benson, explaining, “If you have a 10- to 20-ft window, you wait to slide almost to the edge of the window rather than making small adjustments to maintain position on a trajectory.”

Motive has observed from the more than 225 wells where its system has been used that when smaller adjustments are used to keep the drill path closer to the planned trajectory, the time needed to slide is reduced and results in a smoother, easier path.

“There are lots of rules of thumb for faster drilling that ironically slow drilling and create headaches and are quite expensive,” he said.

Humans Wanted

Drilling rig reality, though, is too messy, imprecise, and prone to conflicting human agendas to turn control over to a logic-based computing machine.

“Well plans change. Data inputs get disconnected. Operator priorities are not always enumerated,” the paper on directional advisors said, adding, “Software operation is much easier when the people responsible for drilling the well are also responsible for providing the input to the software.”

The value of technology will depend on the system used to manage the work. No matter how things change, a human is required to get the credit or take the blame.

“Someone has to be responsible for wellbore positioning. That is something people are forgetting about (when changing the workflow). Someone needs to be responsible for running the operation and the results,” Wylie said.

“In terms of business, we are trying to promote the idea that it is not a threat of your jobs,” Wylie said. Directional drillers will find their jobs easier if they can anticipate problems, help react to changed plans, detect dubious data, and see patterns that suggest there is a better way to do it.

For a driller, the focus is simply on the task at hand, not keeping the well on the correct trajectory, because there are so many other details to tend to. “The driller operates the drilling equipment and manages the crew. He has his own role. It is a huge responsibility,” de Wardt said.;

Over time, they may be focusing more on measures of well quality. While completion and production engineers experience the problems and lost production caused by issues such as sharp bends in the well tortuosity or porpoising (rising and falling paths), there are no industrywide key performance indicators (KPIs).

That is something de Wardt would like to change by organizing a group to develop industry KPIs.

“I think people defaulted to drilling fast. It is a simple measure that gets production earlier and reduced well costs because day rates are involved,” de Wardt said. “We have to have KPIs for well construction related to the longevity of the well.”