Hurricane Harvey gave many SPE members in Houston at least a few days’ experience of life without electricity. Most of us find it hard to imagine what life would be like without the access to energy that we take for granted—the flip of a light switch, heating something in the microwave, or climate control in our homes. Yet nearly 1 billion people on our planet go through their days without electric lights, refrigeration, heating/cooling, clean fuel for cooking food indoors, and more. Those who rely on wood, peat, or dung for cooking spend hours each day gathering fuel. The gatherers are often the women and children, precluding their access to education and other opportunities. Use of kerosene for lighting has been linked to lung cancer, pneumonia, heart disease, and other health problems. Lamps are easily knocked over and start fires. A lack of access to electricity has ripple effects across many aspects of people’s lives, health, and safety.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) reports that in 2017 more than 120 million people worldwide gained access to electricity, causing the total number of people without access to fall below 1 billion for the first time ever. IEA is expecting this reduction in energy poverty to double when 2018 data are available. The United Nations is targeting zero energy poverty by 2030. The gains during 2017 are largely attributable to a significant government effort in India to bring electricity to all of its villages and progress in a few African countries. Despite these gains, more than 55% of people in Sub-Saharan Africa and around 9% of those in Asia still lack access to the benefits of electricity. In 15 African countries, the percentage of the population without access to electricity is 75% or more.

The International Energy Agency defines energy poverty as a lack of access to modern energy services. These services are defined as household access to electricity and clean cooking facilities (e.g., fuels and stoves that do not cause air pollution in houses).

Where did the electricity for those 120 million new consumers come from? Since 2000, according to IEA, 26% of this additional access to electricity has come from natural gas, and to a lesser extent, oil. Another 45% has come from coal (commonly used for electricity in India). Since 2012, renewables have grown in the mix and now constitute 34% of new electric connections in developing areas, led by solar power. Those who argue we should stop using all fossil fuels immediately may not realize that they would be limiting the opportunity of those without power to improve their standard of living.

Progress on ensuring access to clean fuels for cooking has been much slower. IEA estimates that 2.8 billion people lack access to modern cooking fuels, virtually unchanged from 2000. China and Indonesia have made progress through policies encouraging use of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), natural gas, and electricity for cooking. IEA reports that 2.5 billion people cook with traditional biomass sources, while another 120 million use kerosene and 170 million use coal for cooking. Natural gas, LPG, and natural gas liquids have the potential for replacing these sources, with significant environmental and health benefits as well.

Sustainability is about improving people’s lives, both now and for future generations. It is difficult to imagine a more immediate improvement than gaining access to clean, affordable energy. Suddenly there is time for education, a small business, or greater connection with the world beyond a village.

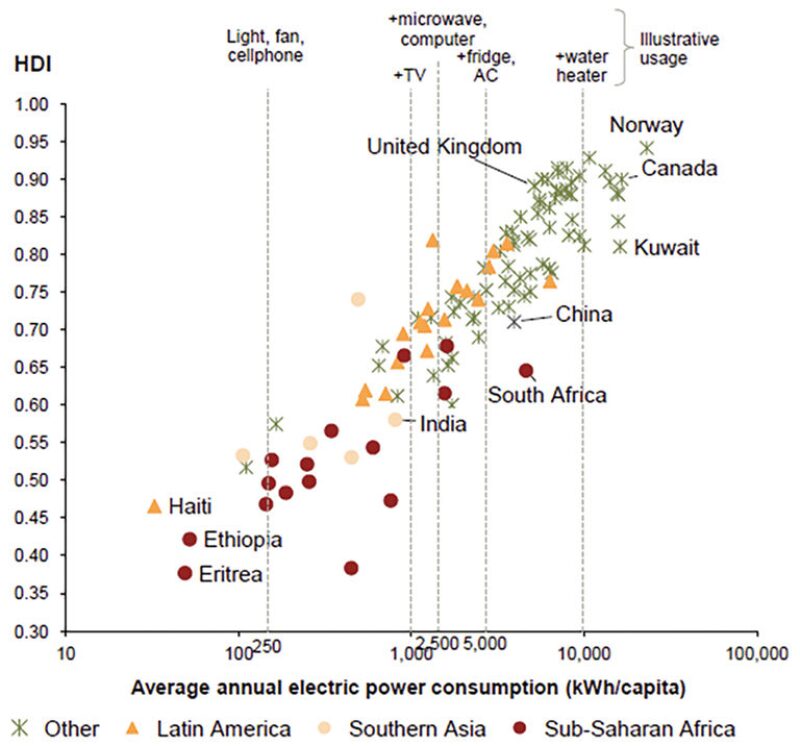

The figure shows the relationship between the Human Development Index and electricity consumption. The dotted vertical lines indicate the amount of power consumption represented. According to the IEA, 1,250 kWh per household will power four light bulbs operating at 5 hours per day, one refrigerator, a fan operating 6 hours per day, a mobile phone charger, and a television operating 4 hours per day. For comparison, the average US household consumes 10,000–12,000 kWh per capita per year. The figure makes clear that access to electricity provides greater socioeconomic development.

Most of the people gaining access to electricity do so through expansion of the power grid. For more remote areas, mini-grids (to power a small village) and off-grid systems (single home) are more practical, and mainly focus on solar photovoltaic systems. Those of you who work for large companies are aware of the significant efforts that many of our employers have put into expanding access to energy through solar and wind power in remote areas. While both can produce only intermittent power, for those who have had no power, they are a significant step up in lifestyle.

Where the power grid is based on coal or diesel fuel, CO2 emissions will rise as connections increase. For those who are gaining electricity and an improved lifestyle, this is a small price to pay. Overall, since electricity is displacing biomass and similar fuels, IEA estimates the net impact on carbon emissions would be small. But with increasing climate concerns, there may be an alternative way of meeting growing needs for electricity, especially in Africa—natural gas. With lower emissions than coal or diesel, natural gas is an opportunity to reduce net emissions.

There have been a number of sizeable natural gas discoveries in Sub-Saharan Africa in recent years. Earlier this year, Total announced a significant gas condensate discovery off the coast of South Africa. BP and Kosmos Energy made a major gas discovery off Senegal and Mauritania in 2017. Mozambique and Tanzania have discovered large gas reserves in the past decade. Equatorial Guinea has signed gas supply agreements with Ghana for domestic use. Nigeria and Angola have significant natural gas reserves as well. At least nine African countries are evaluating liquefied natural gas (LNG) export opportunities which will result in job creation, economic growth, and an increase in gross domestic product. But the potential exists for using some of this gas to supply domestic needs as well. The challenge is infrastructure—building the power plants to generate electricity from natural gas and expansion of the grid to reach a great portion of villages. This, again, is where our companies can help.

As an example, in Nigeria, the gas turbines at the Nigeria LNG plant and a nearby oil export facility on Bonny Island are producing electricity that is sent to a grid that supplies local businesses and homes with clean, affordable energy, benefitting more than 90,000 people. The potential for cogeneration of electricity exists at many types of facilities operated by our industry around the globe. Making investments of this type that can have such a profound impact on people’s lives is corporate social responsibility at its best. Sustainable activities can be a sound business opportunity as well.

Support from our industry can help to raise standards of living while countries work on expanding their electric grids and adding new generation capacity to create reliable supplies for the longer term. The African Development Bank is funding a range of projects to expand the grid, as are the World Bank and others.

The potential of natural gas to reduce energy poverty is not limited to Africa; parts of Asia and Latin America could also make use of local natural gas resources to produce electricity and lift some of their poorest communities out of poverty. What our industry has sometimes viewed as “stranded gas” may in fact be in areas with the greatest need. The OPEC Fund for International Development is also funding a range of electricity projects—in Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia—spanning solar, wind, and fossil fuels.

Briefly try to imagine what your life might be like without access to electricity or safe and clean cooking fuels. Then think about the difference that access to even a modest amount of power would make to poor and needy people around the world. Energy poverty is a problem with a solution. It is not a quick or easy solution, but one where our industry is well positioned to help. Natural gas holds the potential to provide clean, affordable, reliable power to those without it. Finding and developing natural gas resources, coupled with the efforts of our industry and others to create the infrastructure to convert it to electricity and deliver it to homes, will have a major impact on improving people’s lives. What better feeling than putting a smile on the face of a needy child, providing power to a hospital or school in a remote village, or providing clean cooking fuel to families currently using basic biomass sources. Our job is not limited to discovering and selling oil and gas; we also improve people’s living conditions, support their economies, and enhance their social opportunities. That is definitely something we can take pride in.

To contact the SPE President, email president@spe.org. Follow him on Twitter: @neaimsa.