There is a large divide in the cost of drilling and operating wells between big and small companies in Texas and surrounding states.

Big companies have a decided cost advantage over smaller competitors when it comes to the cost of operating wells and deciding whether the oil price justifies drilling new wells, according to responses to the monthly survey of executives in the business by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The dominance of a small group of major players has grown over the past year due to mergers consolidating control in the Permian and other shale basins.

One motivation is the savings that come with merging overlapping operations, such as accounting and administrative functions, when two companies combine.

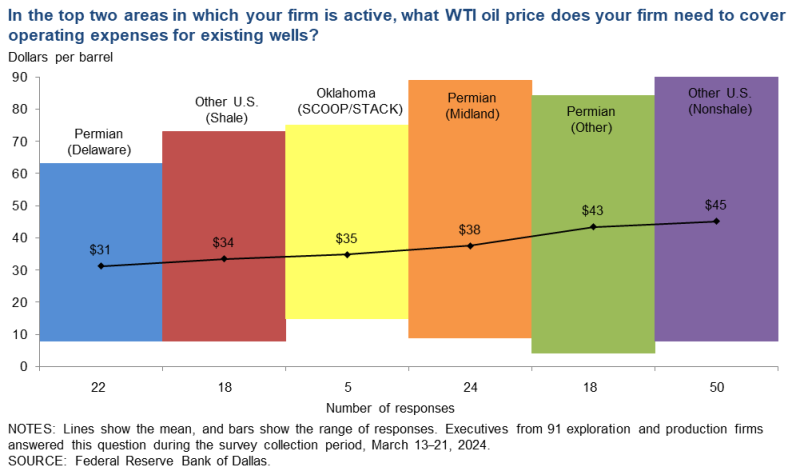

Based on a survey of 91 oil and gas executives, production is profitable in the major shale plays for all operators. The average price of producing a barrel of oil ranges from $31/bbl in the Delaware Basin of the Permian to $38 in the Midland Basin. Operating costs in other US shale plays average $34.

But it is significantly less profitable for small operators, according to the survey. Those producing less than 10,000 B/D reported paying an average of $44/bbl to produce oil, compared to $26 for those above that line.

When deciding whether to drill new wells, small operators said the breakeven level is $67/bbl, while executives in larger companies said the oil price needs to be at $58 to profitably drill.

Oil prices at $80 currently are high enough to make earning a profit possible at all those price points. This is largely testimony to years of industry efforts to increase well productivity and reduce costs because a dollar buys a lot less than it did in 2014 when the run of $100/bbl oil prices ended. An $80 barrel now is worth $60, based on the value of the dollar at the start of 2015. Back then, prices approaching $50/bbl were enough to trigger mass layoffs.

Now it is just the backdrop for dull times. Based on the Dallas Fed’s survey, oil industry activity, costs, hiring, and the outlook can all be described as flat.

The survey does not try to explain why large oil companies have an edge. This marks the first time the question has been asked, so there is no way to know what this gap has historically been, though the responses about price ranges have consistently shown a significant variation in costs among companies.

It would make sense that big companies would pay less because they have greater buying power and greater access to capital markets at a time when bank lending rates are up, and loans are harder to get.

Their greater resources allow them to acquire large stocks of prime acreage for drilling, plus the money and technical expertise to deploy new technologies to maximize the value of their development programs.

A recent report by the US Energy Information Administration revealed that the US was once again the world’s largest producer of oil and gas. However, the increase in production has not provoked more drilling activity.

According to the report, “These record highs have come despite declining US drilling activity” because technology advances are “enabling US producers to extract more crude oil from new wells drilled while maintaining production from legacy wells.”

Surging production from new shale wells, and higher output as they age, helps explain the cost gap. Those with more money and acreage are adding high-producing new wells at a cost far less per barrel to run than those whose holdings tilt toward wells that are a few years old, where the cost of pumping and water disposal is spread over far fewer barrels.

Service Suffers

Service companies also have little to celebrate according to the survey which said their executives “reported modest deterioration in nearly all indicators.” Those include the reduced demand for their equipment, lower operating margins, and continued lower fees for their services.”

All of which led one anonymous commenter to raise a question regarding potential effects on the service sector: “Our biggest concern is the evolving merger and acquisition activity for US E&P operators. As the operator pool shrinks, the oilfield services will inevitably follow suit. This leads to concerns on additional oilfield services mergers, or worse, aggressive pricing from competitors striving to stay alive.”