The long heralded “big crew change” in the industry might best be described as a changing of the guard: an older generation of experience stepping down, leaving large shoes to be filled by the younger generations behind them. Depending on who tells this tale, it can be anything from a disaster to an excellent opportunity. A disaster for companies as decades of experience and expertise are lost to them; an excellent opportunity for a younger generation in a down market—senior positions will need to be filled, and senior level experience will not be competing against them. Regardless of the narrative, what we know about the big crew change is that we know little. Competing narratives make it even more difficult to evaluate. Has the worst of it already passed, leaving the industry relatively unscathed?

For the optimists, there are favorable signs abound, signaling that executives are confident that their preparation for the big crew change have left their companies well situated. The pessimist on the other hand, believe the worst is yet to come; that the big crew change is still happening and, combined with too many cycles of downsizing activities, we may never know for certain whether or not it has happened or it is still happening. In this article, the authors will be exploring the impact this change, whether positive or negative, have on companies, labor, and the academia.

Companies: Preparing Younger Talent To Lead |

|---|

As their own experienced employees step down, they [companies] turn to independent consultants to provide experience. This is the most negative impact of the big crew change for young professionals, as it removes opportunities to step into important, challenging roles in which they can experience significant development as engineers and leaders.

Several oilfield service companies and major exploration and production companies have spent years trying to prepare for the crew change, according to the Financial Post. Baker Hughes has run mentoring programs for young engineers while ExxonMobil has spent approximately $2.6 million on workforce training initiatives and ad campaigns encouraging young students to pursue STEM careers. Halliburton has continued to hire new grads from college—despite a sometimes adverse services market—to keep the talent pipeline full in order to minimize the impact.

National oil and gas companies are also employing ways to retain knowledge and experience within their organizations. One key component proposed by the Abu Dhabi Company for Onshore Oil Operations is to reduce the time it takes to develop technical skills and the required confidence to be independent contributors through competency-based training programs based on learning style, skill matrices, and assessments. Several measures are being taken by oil and gas companies to help speed up the transition. These are broken down into knowledge capture, microlearning, blended learning, and the use of consultants:

Knowledge capture. Coincidentally, the big crew change is happening at the same time as digitalization is taking a bigger role in the industry. The use of knowledge repositories is not new in the industry. However, the level of adoption and scalability has increased quite dramatically. For example, Halliburton developed knowledge capture portals where employees can ask questions and expect to get a response from more experienced professionals. This has since evolved into SharePoint sites for various product service lines and more recently an open chat room where employees can ask questions, share ideas, and provide feedback.

Blended learning. A combination of web training, classes, workshops, conferences, mentoring, peer reviews, business simulation, and on-the-job-training, the idea behind the blended learning approach is to twofold: reinforced learning and catering to individual preferences. Some people prefer the interactions as in classroom setting or one-on-one mentoring sessions while others are comfortable learning via web training. The drawback of the latter is that questions provided for assessment are structured but in reality, challenges encountered on the job are unconstrained. Thus, effective learning requires a blend of both approaches.

Microlearning. Shorter bursts of training are some of the other measures companies are adopting. Most of these types of learning are through online resources suitable for young professionals rather lengthier formal training programs. The effect of the crew change demands young professionals be adaptive and learn quickly for immediate application to their current role. The challenge with this approach is the availability and timeliness of the material they need.

Consultants. The role of consultants has increased dramatically in the past few years not only because of the price crash but also because of the big crew change. As competition for capital increases, companies are more likely to use experienced professionals for project startup, execution, and closeout in order to minimize the impact of this crew change that has now come. As their own experienced employees step down, they turn to independent consultants to provide experience. This is the most negative impact of the big crew change for young professionals, as it removes opportunities to step into important, challenging roles in which they can experience significant development as engineers and leaders.

Labor: How Deep is the Talent Pool? |

|---|

...[T]he timing of this shift coincided with the beginning of the US shale revolution, which may have mitigated the impact of some lost experience. For companies operating in the US especially, this meant that their employees were facing an entirely new set of challenges...

The big crew change was supposed to leave companies not with a dearth of talent but with a dearth of experience. This would be devastating for companies that had not sufficiently passed knowledge from one generation to the next. As any recent graduate quickly discovers, the gap between classroom theory and industry application can be, at times, quite extensive. Experience is the bridge for this gap. Once an employee has “seen it all,” reacting to unexpected circumstances becomes a matter of drawing old tricks out of the hat, rather than needing to forge a path through trial and error.

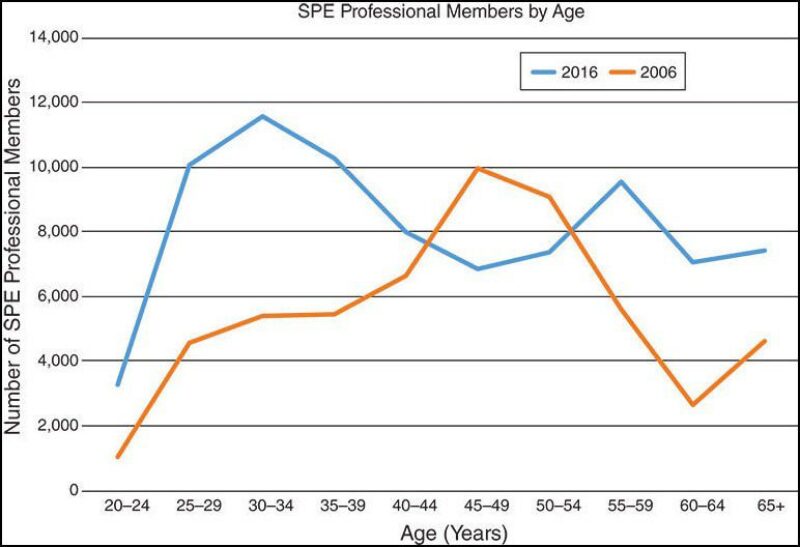

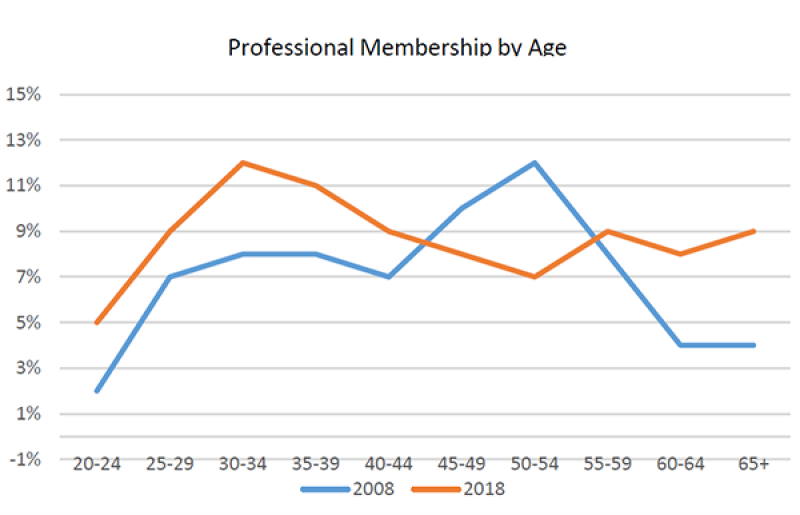

There is no doubt that the demographic of the industry has changed in the last 10-15 years. The age distribution of SPE professional membership demonstrates this (Fig. 1 and 2). A plurality of 45-49-year-olds has been displaced by a plurality of 30-35-year-olds in the last decade.

Fig. 1—SPE professional membership. (Source: JPT.)

Fig. 2—SPE professional membership by age. (Source: SPE.)

However, there are three important points regarding this shift that suggest that while the age distribution may be shifting, decades of experience and wisdom did not suddenly become unavailable to companies. First, we see that the 45-49-year peak seen a decade or so ago did not translate to a drop in recent years—the peak merely shifted to the right. This suggests that experienced professionals are not dropping out of the industry—they are maintaining their involvement, whether through full-time employment, consulting gigs, or semi-retirement.

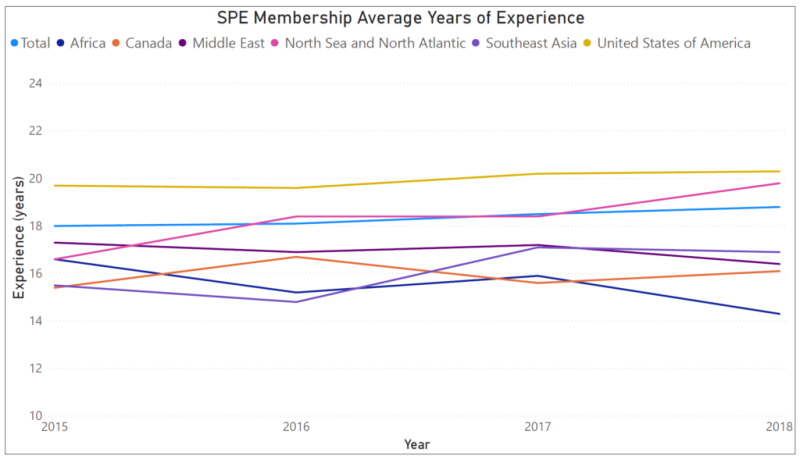

Second, this shift has occurred gradually enough that any old hand on their way out the door has had plenty of time to transfer their accumulated wisdom to their up-and-coming replacements. There have been concerns that the recent downturn would lead to a sudden drop in experience levels, but the data do not bear this out. The available information from SPE annual membership surveys (going back to 2015, the onset of the downturn) shows that experience levels have stayed extremely steady across regions (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3— SPE membership average years of experience for different regions. (Source: SPE.)

Third, the timing of this shift coincided with the beginning of the US shale revolution, which may have mitigated the impact of some lost experience. For companies operating in the US especially, this meant that their employees were facing an entirely new set of challenges such as mapping out and developing infrastructure for basins that were nearly untouched previously, optimizing horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing on previously unseen scales, and optimizing production and understanding the behavior of wells and reservoirs that have not previously been economic. While experience still has cross-disciplinary value, the loss of a 30-year subsea specialist is much less devastating to a company pivoting to shale than one that is doubling down on offshore prospects. Thus, at the time of retirement, many experienced industry members have as much (or less) experience with unconventional reservoirs and everything surrounding them as the individuals stepping up to replace them.

Academia: Adapting to the Needs of the Future |

|---|

Petroleum engineering degree-holders should be, bar none, the natural first choice for petroleum engineering positions.

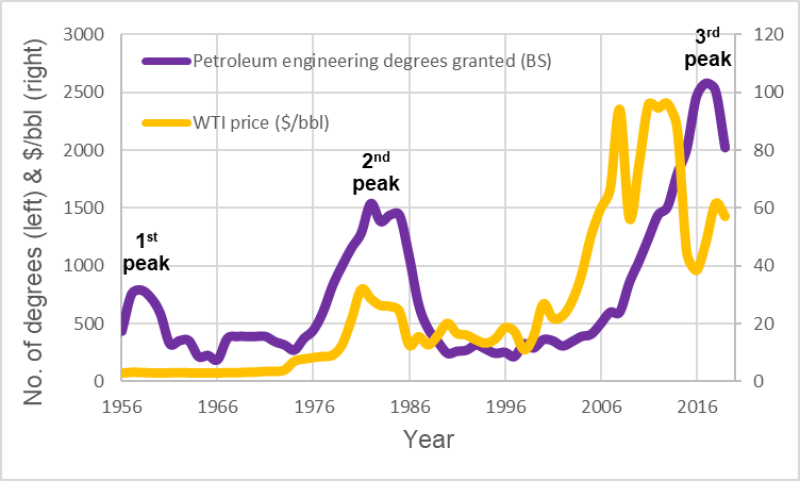

The big crew change is expected to leave its footprint on the petroleum engineering academia. Data on the number of petroleum engineering BS degrees awarded since 1956 (Fig. 4) show that three peaks have occurred—in 1958, 1983, and 2017 (Zborowski 2018, Heinze et al. 2019). The two most recent peaks are indicative of the cause of the big crew change observed today. Looking at Fig. 4, we can also observe that in the recent years compared to the past, (1) the number of degrees granted is more sensitive to fluctuations in the oil price, and (2) a time lag has developed in the number of degrees granted, responding to the crude spot price.

Fig. 4—The number of BS petroleum engineering degrees granted in 1956-2019, where three distinct peaks can be seen in 1958, 1983, and 2017. (Source: Financial Post 2016, Daghar et al. 2016.) The WTI spot crude prices are shown for the same time period. (Source: US EIA)

Petroleum engineering degree-holders should be, bar none, the natural first choice for petroleum engineering positions. Their educational background should grant them a competitive advantage over other engineering degree competitors. An advantage which should not be easily nullified by a few in-house training courses. However, this does not seem to be the case today, which suggests there is room for development in academia.

Over the years, university classes taught by faculty of diverse educational and professional background have given students the false impression of petroleum engineering curricula consisting of sets of discrete and disconnected disciplines that may not utilize modern technologies (Zborowski 2018). As a result, students struggle in retaining and applying concepts from one class to another and can enter the workforce without touching industry-standard software. Academic programs interested in facilitating a smooth transition of their graduates into the industry should work in conjunction with practitioners to design curricula (Heinze et al. 2019) which can ensure that once the oil and gas prices go up again, the employment opportunities opening up are filled with candidates of relevant education and professional experience.

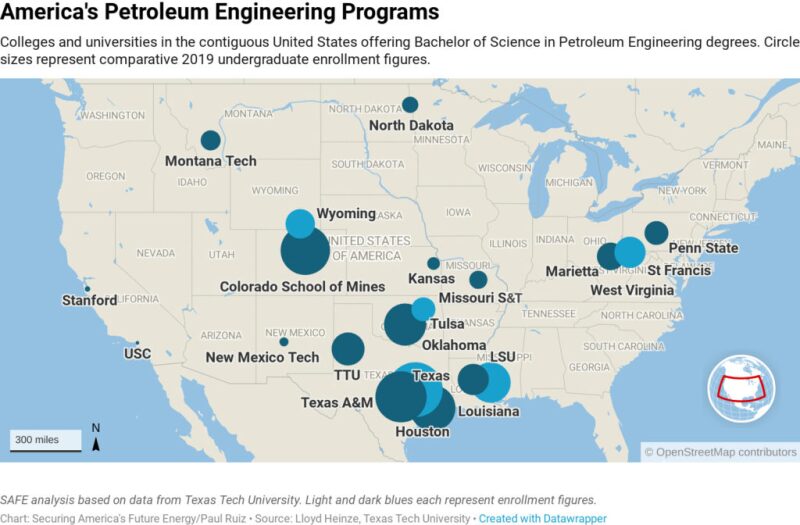

Nevertheless, the big crew change provides an opportunity for a positive change in petroleum engineering academia. The increase in petroleum engineering student enrollment since the mid-2000s (Zborowski 2018, Heinze et al. 2019) (Fig. 4-5) will provide future faculty candidates who combine relevant educational background and professional experience (Michael 2018). This will strengthen the core of academic programs, combining coursework and faculty to shape students into well-rounded, market-attractive professionals with the knowledge and understanding necessary for tackling complex petroleum engineering problems.

[Click to expand.]

Fig. 5—Petroleum engineering undergraduate enrollment in US universities. (Different shades of blue used in overlapping circles to distinguish colleges/universities from each other.) (Sourced and edited from Energyfuse.org.)

Conclusion |

|---|

Whether or not the big crew change has happened or is still happening, the mere anticipation of the event has affected oil and gas companies, their workforce, and the academic community. The impact on companies are mostly positive as preparations have left them with a well trained workforce and the tools to make sure future generations are similarly well trained.

The potential negative impact may be to the workforce and academia as current skill sets from universities may just not be enough to meet the current needs of the industry, causing companies to turn to independent consultants. Likewise, workers, especially young professionals, will have to adapt quickly and be ready to take up more responsibility and own large projects. The oil and gas companies will have to do a lot more to keep the talent pipeline flowing so this big (bad) crew change will never be a concern in the future.

|

James Blaney |

|

|

| Ighalo | Blaney | Michael | Dokun |

Samuel Ighalo is drilling advisor, consulting and project management, at Halliburton and is responsible for providing well engineering support to oil and gas operations across multiple regions, including North America, Europe, North Africa, Middle East, and Latin America. Ighalo has 14 years’ industry experience and previously worked as drilling engineer for Korea National Oil Corporation. He holds master’s degrees in petroleum engineering (Smart Oilfield Technology Option) from University of Southern California and in petroleum engineering and project development from the Institute of Petroleum Studies (IFP France and University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria).

James Blaney is an engineer on the technical development team at Liberty Oilfield Services. He works with current and emerging technologies to improve efficiency, accuracy, and safety in the field. Previously, he was a field engineer on Liberty's fracture fleets in the Permian Basin. He holds a bachelor's degree in petroleum engineering from the Colorado School of Mines and a bachelor's degree in economics from Georgetown University.

Andreas Michael is a petroleum engineering PhD student at the Louisiana State University (LSU), researching topics related to hydraulic fracturing. His professional interests include unconventional reservoirs, petroleum geomechanics, petrophysics, economics, and geopolitics. He has broad intra-disciplinary knowledge, becoming a PetroBowl World Champion with LSU in 2019, and placing second at the SPE International Student Paper Contest the same year. He holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in petroleum engineering from the University of Texas at Austin.

Oyedotun Dokun is a business development professional with OES Energy Services. He has both shore- and rig-based experience spanning over a decade and supervised successful drilling campaigns for companies such as Chevron, Agip, and Shell. He is a mechanical engineer and IWCF-certified (Level 4) Drilling Well Control Supervisor. As a John Maxwell Certified Coach, he facilitates group and personal coaching sessions for individuals and corporates. Dokun is currently an MBA candidate at the University of South Wales.