Saipem’s flagship vessel Castorone was contracted to start work this summer on Turkey’s offshore deepwater Sakarya gas field while neighboring Romania prepared to enter Phase 2 of its Neptun Deep gas project.

Blessed with some of the same source rock as the hydrocarbon-prolific Caspian Sea (they were one sea in the geologic past), the Black Sea has long been regarded as a frontier basin of great promise, but with unique challenges—earthquakes, sheer slopes plunging to 2200-m depths where sediments are unstable, its bottom-water harbors H2S instead of oxygen, and complex life is nowhere to be found.

Straddling Europe and Asia, the Black Sea is surrounded by Turkey, Russia, and other remnants of the USSR and the czarist empire before it: Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine, and Georgia. There is also only one way in and one way out, via Istanbul and the Bosphorus Strait whose width varies from 3.7 km (2.3 miles) to 750 m (2,450 ft).

The Bosphorus has long been the southern export route for Russian (and Soviet) oil loaded on tankers at Novorossiysk for transport to the Mediterranean, and over years the Black Sea has become crisscrossed by gas pipelines, most notably the Blue Stream and TurkStream, which seemingly cemented Turkey’s role as a transit state and major consumer of Russian gas.

Times, though, have changed.

With energy security through diversity of supply now top of mind, Romania and Turkey are driving their own exploration and production projects to identify and develop deepwater gas reserves to supply domestic needs as they simultaneously strategize to become future exporters through such infrastructure as the Trans Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) and liquified natural gas (LNG).

Ukraine and Russia, meanwhile, are the wildcards in the region, considering that the largest deepwater deposits in the Black Sea are believed to lie in the unexplored waters of Ukraine.

Neptun Deep To Position Romania as Largest EU Gas Producer

In June 2023, 50/50 partners Austria’s OMV Petrom and Romanian state-owned Romgaz Black Sea Ltd. took a final investment decision (FID) to proceed with their $4.4-billion Neptun Deep gas project, which data and analytics provider Wood Mackenzie (Woodmac) notes, will make Romania the largest gas producer in the EU.

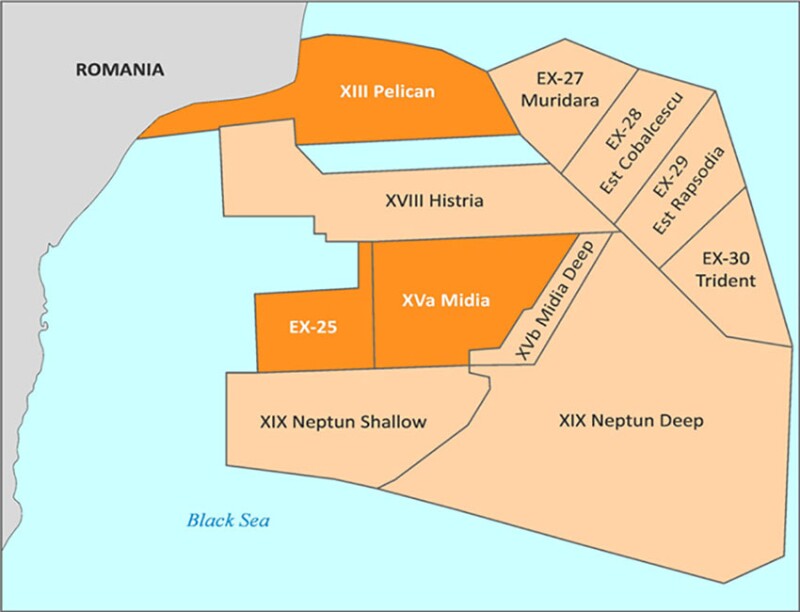

Neptun Deep is the first deepwater development on the Romanian shelf which is part of the northwestern Black Sea Continental Shelf (Fig. 1). According to Woodmac, it was the EU’s largest upstream FID in 2023.

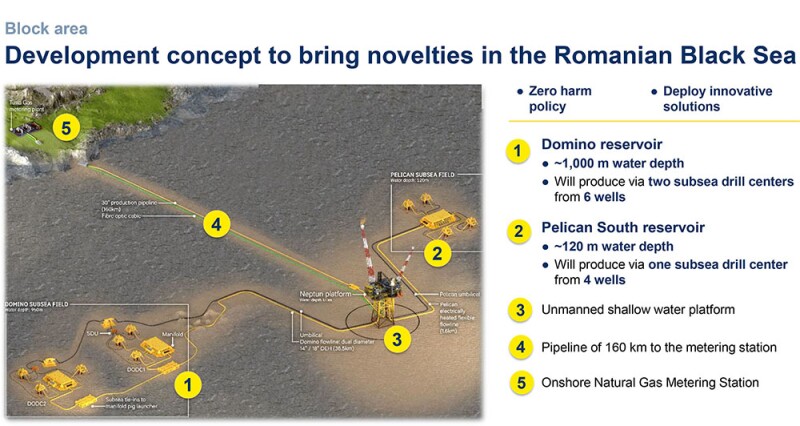

With an estimated 100 Bcm in reserves, Neptun Deep aims to produce first gas in 2027 from two fields: the deepwater Domino gas field at 1000-m depth and the shallow-water Pelican Sud (South) at 120-m depth. The project’s 10 wells will tie back to an unmanned shallow-water platform and will deliver 8 Bcm/yr (775 Mcf/D) of gas at plateau for about 10 years (Fig. 2).

Neptun Deep’s plateau output will boost OMV Petrom’s production mix to 70% gas from the current 50%, a goal the Austrian operator has set for itself by 2030.

In December 2023, OMV Petrom announced it had awarded 80% of the execution agreements it would need to deliver Neptun Deep on time and in budget. Major awards included:

- A $357-million contract engaging the Transocean Barents semisubmersible drilling rig for a minimum 1½ years to drill the project’s 10 wells starting in 2025. The Barents’ Class 3 dynamic positioning capability, anchors, and dual RAM rigs, enable drilling in both shallow and deep water.

- Halliburton Energy Service Romania and Newpark Drilling Fluids Eastern Europe scooped a $154-million contract for integrated drilling services.

In August 2023, OMV Petrom awarded Italy’s Saipem a $1.8-billion engineering, procurement, construction, and installation (EPCI) contract that included

- A gas processing platform in 100 m of shallow water. Saipem will fabricate the platform at its yards in Italy and Indonesia with the Saipem 7000 and JSD 6000 vessels conducting offshore operations.

- Three subsea developments (two in 1000-m-deep water in the Domino field and one at around at 100-m water depth in the Pelican field) and the associated flowlines and umbilicals.

- A 30-in. gas pipeline about 160 km long, and associated fiber-optic cable from the shallow-water platform to Tuzla on the Romanian coast and a gas-metering station.

The offshore platform is designed to generate its own power while the wells and fields are operated remotely through a digital twin. A key aspect of the development concept is that natural reservoir energy is used to transport the gas to shore, eliminating the need for gas compression and helping to keep emissions below industry norms, according to OMV Petrom.

Romania’s Shallow Water Has Been a Mainstay for Decades

While Neptun owns bragging rights to being the Black Sea’s first deepwater drilling project, shallow-water projects have been doing their part for decades in Romania.

OMV Petrom said it is now drilling two new wells in the Istria block to enhance production from the Lebada East field, which has been operational since 1979.

New projects like Romania’s Midia Gas Development Project which produced first gas in 2022 was hailed as Bucharest’s first new offshore gas development since 1989.

Midia’s five production wells are now producing 1 Bcm/year of gas, about 10% of Romania’s consumption, according to independent operator Black Sea Oil & Gas S.A. (BSOG) which holds a 70% stake.

Infrastructure includes one subsea well at Doina field and four platform wells at Ana field connected through an 18-km pipeline to the new unmanned production platform at Ana. A 126-km gas pipeline then links the Ana platform to the shore and to a new onshore gas treatment plant in Corbu commune, Constanța County.

Carlyle International Energy Partners and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development own BSOG whose Midia partners include Petro Ventures Resources SRL (20%) and Gas Plus Dacia SRL (10%).

Gas Plus SpA is Italy’s fourth-largest gas producer and owns a supply chain that includes delivery to retail customers, which could be significant in light of London-registered Energean’s plan to complete the sale of its portfolio in Italy, Egypt, and Croatia to Carlyle by the end of this year.

Romanian press in July reported that Hungary’s MOL was negotiating with Russia’s privately held Lukoil Overseas to acquire the 87.8% stake in the exploration license that the Russian company holds in the EX-30-Trident gas exploration area through 2026 and its 20% stake in the Ploieşti refinery. Partner Romgaz with a 12% stake would have first right of refusal should Lukoil seek to divest.

Turkey’s Deepwater Game Changer: Sakarya Is Bigger and It’s Already Producing

About 335 km south of Romania’s Neptun Deep—in Turkish waters—is the Sakarya field whose gas reserves are estimated at 710 Bcm, and at seven times that of its EU neighbor, it is the largest hydrocarbon discovery made to date in the Black Sea.

In August 2020, Turkish Petroleum’s Fatih drillship confirmed a discovery of gas in the Tuna‑1 prospect which was then renamed the Sakarya gas field.

Initial reserves estimated for Tuna-1 totaled 320 Bcm (11 Tcf) of natural gas. However, after the Amasra-1 well was drilled in June 2021, another 135 Bcm was added, bringing the field’s total reserves to date to 540 Bcm (19 Tcf).

In December 2022, TPAO (Turkish Petroleum) raised the estimate again to 710 Bcm based on results obtained from the Çaycuma-1 well, as announced by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s office.

Turkey has now turned to drilling the Filyos-1 well which is a new exploration area that is not part of Sakarya where TPAO’s Fatih drillship has drilled appraisal wells while its ultradeepwater drillship Kanuni dealt with completions and borehole testing.

A total of 10 appraisal wells have been planned for the first phase of the project. Four wells have been drilled so far—Turkali-1, Turkali-2, Turkali-3, and Turkali-4.

TPAO commissioned Phase 1 of the Sakarya project in April 2023 after Italy’s Saipem, in consortium with SLB and Luxembourg-registered Subsea7, fast-tracked execution of an EPCI contract that the Turkish Petroleum Offshore Technology Center (OTC) had awarded in 2021.

Having brought 10 wells onstream with the completion of Phase 1, production of 6 million m3/D of gas is now flowing to Turkey’s domestic consumers, according to a recent statement by Energy and Natural Resources Minister Alparslan Bayraktar.

Ashley Sherman, research director, Caspian and Europe Upstream Oil and Gas at Woodmac, said at the time that while achieving first gas in deepwater “redefines the scale of Turkey’s upstream sector … Phase 2 would be a real game changer, enabling Sakarya to cover almost 30% of Turkey’s gas consumption by 2030.”

In May 2023, just 1 month after commissioning Sakarya’s first phase, Turkish Petroleum OTC moved swiftly into Phase 2, awarding another EPCI contract to Saipem in the same consortium with OneSubsea (SLB’s subsea technologies, production, and processing systems business) and Subsea7.

Included in the EPCI contract is the development of 26 more wells to boost production capacity by an additional 30 million m3/D by 2028 when Phase 2 is expected to be commissioned, according to SLB.

To date, Turkey has relied almost entirely on imported gas which in 2022 cost Ankara $97 billion, according to Woodmac. These imports have included pipeline gas from Russia, Azerbaijan, and Iran plus purchases of LNG from Qatar and the US.

ExxonMobil inked a long-term LNG sales agreement in May 2024 with Turkey’s state pipeline company, BOTAS, to satisfy up to 8% of Ankara’s demand.

In reporting the signing, the Middle East independent news agency Al-Monitor pointed out that Turkey has ambitions to become a regional hub and major exporter of LNG itself over time, considering it is crossed by seven international gas pipelines and claims five of its own LNG facilities, three floating storage and regasification units, and two underground natural gas storage facilities.

Turkey can export Black Sea gas to Europe via the Trans Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) that joins the Southern Gas Corridore (carrying Caspian gas from Azerbaijan) at the Greek-Turkish border.

Black Sea Reserves, Caspian Sea Source Rocks, East Med Similarities

In 2023, the US Geological Survey (USGS) estimated undiscovered, technically recoverable mean resources in the Black Sea at 105.5 Tcf of gas and 2.3 billion bbl of oil, using a geology-based assessment methodology.

Focusing just on gas, that equates to the 110.5 Tcf that USGS estimated for the Eastern Mediterranean which is “at a similar stage” of exploration as the Black Sea, particularly in deep water, according to the authors of Petroleum Geology of the Black Sea: Introduction.

The paper’s authors (from Halliburton, OMV Exploration & Production GmbH, and the Eurasia Institute of Earth Sciences, Istanbul Technical University) note that the “Kuma and Maykop suites … are important source rocks in both the South Caspian Sea and the Black Sea (as are) sediments from palaeo-river systems … that can form key proven and potential reservoir targets.

“After the discovery of large biogenic gas accumulations (in the Black Sea shallows), the thermogenic petroleum systems (at depths beyond 1000 m) must be proven by systematic exploration of the deepwater and multiple play concepts that exist.”

Or as the head of Getech’s Geoscience Services, (release agent for PetroSeismic Agency Ltd.’s Black Sea well and data sets) explained in layman’s terms: “The shallow waters of the Black Sea can be regarded as being at an immature stage of exploration, further discoveries can be expected.”

Deepwater is complicated because, as Getech notes on its website, the “frontier region that holds the best potential for substantial oil and gas finds … (and) is undrilled” just happens to be the deep waters of offshore Ukraine.

Ukraine—One Step Forward, Many Steps Back

Following a licensing tender, Kyiv chose ExxonMobil and Royal Dutch Shell in 2012 to lead the development of the deepwater Skifska offshore gas field under a production-sharing agreement together with OMV Petrom and Ukraine’s state representative in mineral investment dealings, Nadra Ukrayny.

As was reported at the time, ExxonMobil planned to invest $735 million, earmarking $400 million for seismic surveys and for drilling two deepwater wells, while $335 million would be paid as a signing bonus to the Ukrainian government.

Skifska is situated offshore Crimea in the western Black Sea near where ExxonMobil was at the time drilling the Domino-1 exploration well in Romanian waters (today’s Neptun project). Exxon had eyed Bulgaria then as well because it considered the Black Sea to be one of the few unexplored areas in Europe with significant potential.

Ukraine’s Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources had estimated Skifska’s reserves at 200 to 250 Bcm with 5.0 Bcm/yr production envisioned over 50 years.

All that ended in 2014 with Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the exit of ExxonMobil and Royal Dutch Shell from the project.

Fast forward to 2023 and a Financial Times (FT) report that Oleksiy Chernyshov, chief executive of Ukraine’s national gas company Naftogaz, had met in Washington, DC, with representatives of Halliburton, ExxonMobil, and Chevron to discuss future development of Ukraine’s energy scene.

While the FT characterized talks with Exxon and Chevron as being at an early stage, Naftogaz was reported to be hopeful of signing a contract with Halliburton to help raise domestic gas production to 13.5 Bcm from the 1.0 Bcm produced by Kyiv in 2022.

The latest survey on Ukraine published by the Paris-based International Energy Agency estimated Ukraine’s natural gas reserves at 5.4 Tcm, of which only 1.1 Tcm has been proven. Additionally, Ukraine is estimated to have 400 million tons of condensate and 850 million tons of oil.

The onshore Dnieper-Donets region in the east accounts for 80% of Ukraine’s proven gas reserves and 90% of its gas production. The Carpathian shale region in the west accounts for 13% of the country’s proven gas reserves and approximately 6% of its gas production. With both onshore and shallow-water offshore production, the southern Black Sea and the Sea of Azov region holds 6% of Ukraine’s proven gas reserves and 5% of its total oil and gas production.

Blue Stream Pipeline Crossing Becomes Logistical Masterclass for Saipem

Operational logistics can be complex in the Black Sea, considering that the only way to deliver major drilling and pipe-laying equipment is via the narrow Bosphorus Strait—literally through the center of Istanbul.

From October 1999 to August 2000, the Blue Stream export pipeline project between Russia and Turkey became a testing ground for both Saipem and the industry on how to operate in the Black Sea given the long and steep slopes at both shore approaches and an Abyssal plain section of 240 km at 2200 m depth.

Water depths plus the 24-in. diameter of the twin pipelines crossing the Black Sea through 380 km of subsea environmental and geohazards made Blue Stream the most challenging deepwater pipeline at the time.

The Saipem 7000 laid Blue Stream’s deepwater sections using the J-lay method, while the Castoro Otto laid segments in shallow waters up to 380 m with the conventional S-lay method; but first A-Frames and telecoms structures were lowered to enable the vessels to pass under Istanbul’s three mega-city bridges and enter the Black Sea.

Lessons learned paid off in April 2017 when Russia’s Rosneft and Italy’s Eni contracted Saipem’s Scarabeo-9 mobile offshore drilling unit to drill the Maria-1 oil exploration well on the Shatsky Shaft in Russian ultradeep water that same year.

Saipem drilled 5260 m, just short of the project design depth of 6126 m, in 2125 m of water before western sanctions forced Eni to exit, thus terminating the project in March 2018, as reported in Oil&Gas of Ukraine.

Drilling results did, however, leave a legacy for the future as it had revealed a fractured carbonate reservoir with a capacity exceeding 300 m that Rosneft reported in a press release was highly likely to contain hydrocarbons. The discovery further unmasked a number of giant ultradeep oil concentrations at depths exceeding 10 km, confirming the possibility of the existence of hydrocarbon deposits at significant depths.

Geopolitical Risk? That’s Nothing Compared to Mother Nature’s Challenges

If you Google why the Black Sea is called “black,” you get multiple answers based on a range of speculation, mostly related to history, culture, and language. One provable answer, though, is that water in some of the deepest parts of the Black Sea really does look black.

That’s because high concentrations of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRBs) collect in mud and water layers closest to the seafloor below 150 to 200 m where the environment is anoxic (without oxygen). SRBs produce hydrogen sulfide (H2S) which takes corrosion risk to a new level and can sour oil and gas (NACE-02015).

The Black Sea is known to be the largest anoxic water basin in the world, with over 75% of its bottom sediments and deepest water devoid of oxygen and complex life.

It is also geologically unstable due to soft sediments, methane vents, tectonically active fault lines (earthquakes occur yearly on average, mostly in the north and east), and methane hydrates that are common on the seafloor and can lead to massive sediment movements if destabilized (OTC 12069).

For Further Reading

SPE-0524-0078-JPT Solutions to Complex Well-Testing Challenges Aid Offshore Black Sea Gasfield Development by Chris Carpenter, JPT.

Petroleum Geology of the Black Sea: Introduction by M.D. Simmons, Halliburton; G.C. Tari, OMV Exploration and Production; and A.I. Okay, Istanbul Technical University. Geological Society, London, Special Publications.

Comparative Basin Analysis and Hydrocarbon Generation Model on Examples Rift Systems by D. Tsvitnenko and I. Virshylo, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers.

OTC 12069 Developing Engineering Design Criteria for Mass Gravity Flows in Deepsea Slope Environments by A.W. Niedoroda, C.W. Reed, et. al., URS Greiner Woodward Clyde; G.Z. Forristall, Shell E&P Technology;and J.E. Mulee, Intec Engineering.

NACE 02015 Performance of Aluminum Anodes in Simulated Service Environments Containing Sour Sea Water and Sour Sediment by P. Felton, J.W. Oldfield, and M. Peet, Sheffield Testing Laboratories.