Building better wells requires, “A sense of where you are and how you want to get to where you want to be.”

The observation was from George King, distinguished engineering advisor for Apache Corp., while talking about where well construction is now and where it needs to be after teaching a course on well integrity.

For those drilling horizontal wells, there is the challenge of knowing if the drill bit is within a cone of uncertainty and figuring out how to adjust its path to stay within the most productive part of the formation.

Those completing wells are working in unconventional plays for companies whose top priority is increased cash flow at a time when the price of supplies and services are rising. They need to consider where they want to be in both the short and long term.

The millions of dollars spent to complete the well have an immediate, measurable impact. Over time, those decisions could have a larger effect on production, but that is harder to measure and only becomes apparent over time.

The value of a well sound enough to be modified to take advantage of future enhanced oil recovery (EOR) methods could be huge, but that value is really a wild guess.

“The industry has worked up to 20-25% of the gas in place but we are only at 8-10% of the oil in place recovered,” King said, adding, “The winners will be those who know how to get to enhanced oil production. We need to be flexible enough for EOR later. ”

But there is a catch, “We do not know what future EOR techniques will be in shales.” King said.

A few years ago it appeared that refracturing might be the answer, but jobs repeating the costly pressure pumping process used to stimulate production has never caught on in a big way. The problem is the wells that are good candidates, which includes ensuring the well can handle the stress, may only deliver a moderate production gain and an even faster decline, he said.

“The all-in cost of incremental recovery by the refrac is the limitation. We need to understand how and where gas and liquids flow and to develop techniques to take advantage,” he said.

Those will likely depend on a better idea of where things are, allowing wells that are more precisely drilled and completions targeted to the most productive rock. The future value of wells now will likely depend on whether those older wells are candidates for new techniques.

But for now there are around 1,000 rigs drilling working in the US, and wells must be completed based on what we know now.

Most of the production from shale wells occurs in 5 years or fewer. Historically, though, there are plenty of examples of wells producing far longer than originally expected. King pointed to gas wells in tight rock initially expected to produce for a decade that are still flowing more than 50 years later to make the point that, “We are not just building a well for today.”

What’s Hard?

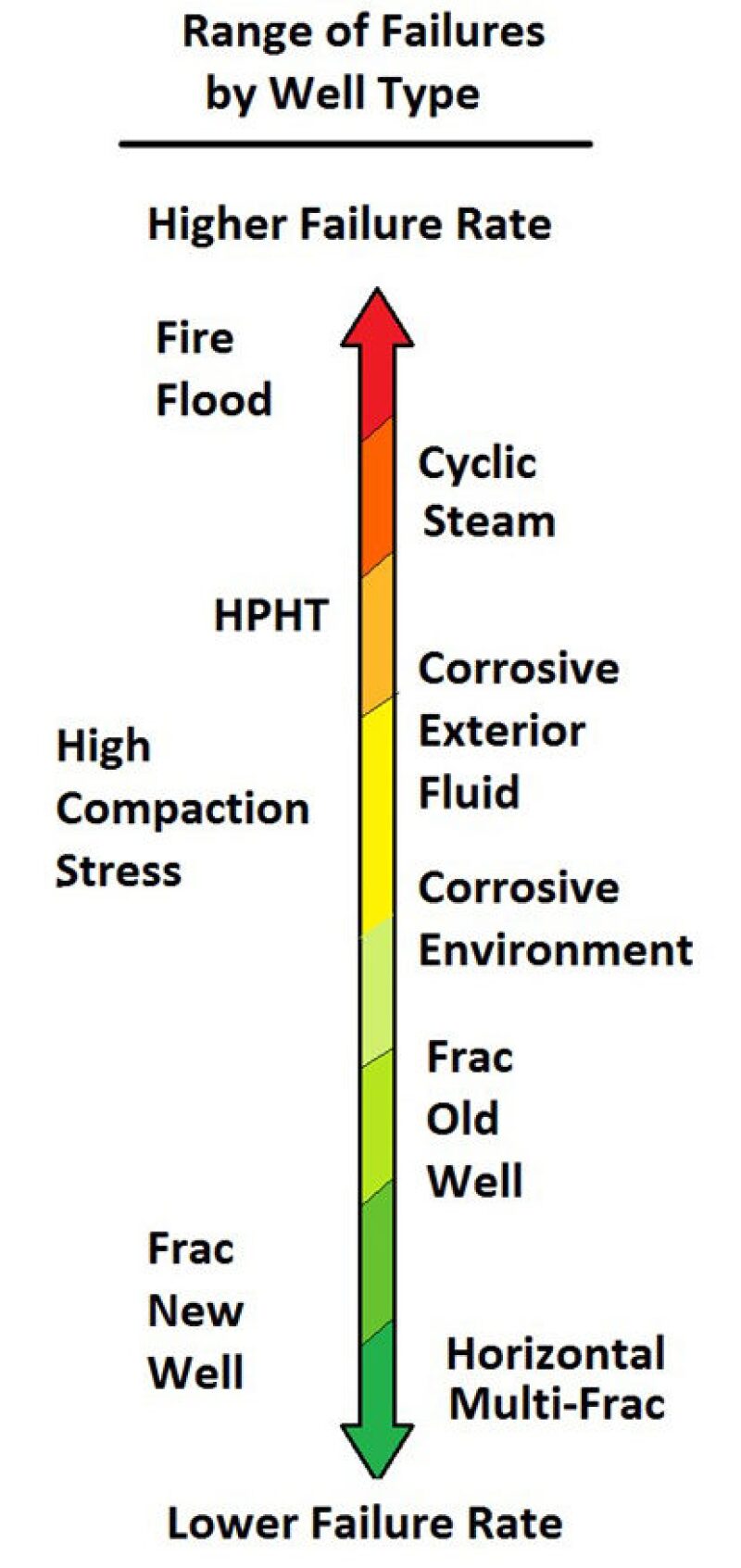

In the ranking of well types most likely to fail, horizontal wells with multiple fractures are low on the list. Structural failures are far more likely in wells that are extremely hot—either naturally or due to steam injection—highly pressured, or where there is enough carbon dioxide or hydrogen sulfide to cause significant damage.

The greater risk for unconventional wells is financial. While well plans are approved based on a relatively short payback on the well cost, most drillers and completion engineers are working for companies that have poured far more cash into developing reserves than has ever flowed out of the ground.

Success is measured on the cost of the completion and the ultimate production. The former is easier to measure and control. One widely used cost cutting method has been factory drilling—mass producing a well design. Using a standard method reduces design costs, speeds work and enables bulk purchases of hardware at a discounted price.

“If you are in a similar geologic setting you can do it. If you are going from field to field that is a risk,” King said. The advice to the class was when it comes to large scale development: “please get away from cookie cutter well designs.”

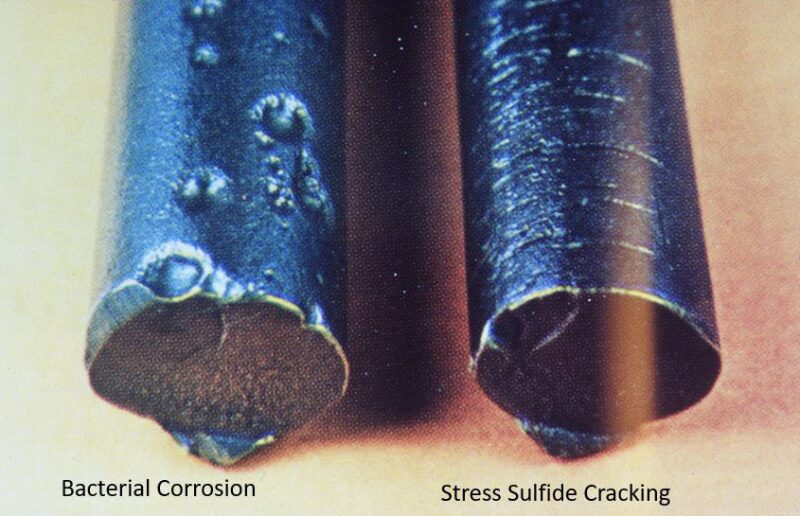

Short term cost savings can have long-term consequences if the well design does not reflect where you are. For example the presence of carbon dioxide or hydrogen sulfide in some wells will require significantly more expensive pipe made to resist corrosion or cracking due to embrittlement.

“As engineers we are not looking at some of the chemical aspects which are pretty important,” King said.

Built for Change

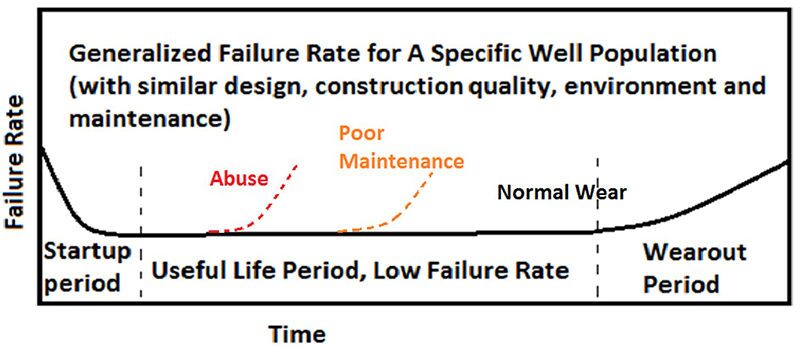

Unconventional wells are not a great source of cautionary tales for a well integrity class. “We are getting a lot more wells we do not have more incidents. In fact the number of incidents per well is going down,” King said.

But at this point an old shale well is not much more than a decade old. Their resilience could be tested if new EOR methods require modifications. On the lists of well risk factors are for wells with a “usage change” and “repurposed wells.”

Repurposing can range from from installing a gas lift system for artificial lift—the tubing must handle the pressure of the gas delivery system used to reduce the density of the crude making it easier to lift—to converting a production well to a water an injection well.

The risk associated with usage changes, will also be there as wells are modified for future EOR methods. While methods have yet to be developed, they will require sound casing and pipes, isolated by a sound cement barrier with well-maintained wellheads and surface equipment.

Based on the course, the best option long-term is not likely to be the well drilled in record time, or completed the cheapest.

For example, isolation requires a cement barrier of from 0.75 in to less than 3 in. Paying for centralizers with stout struts to maintain the gap are strongly recommended to ensure those gaps.

Sharp turns during directional drilling can making casing with centralizers difficult, and tight doglegs could cause cement to buckle.

About 25 ft of good cement can confine pressures as high as 10,000 psi. Creating that barrier requires thoroughly flushing out the annulus to remove drilling mud or other solids that can lead to leak paths, and running from 200-400 ft of cement is advised to ensure that barrier.

Wells must maintain a secure cement barrier to prevent ground water pollution, prevent the buildup of gas pressure of gas leaking into the annulus, and limit casing exposure to corrosive salt water.

Monitoring and maintenance are also critical to retaining the value of what is built. Early warnings will reduce the cost, and downtime of keeping wells running. Success is based on attention to many, many details, based on his experience King has found that check lists have little value.

One negative is these lists can get intimidatingly long. One slide showed a list with so many items the print was unreadable even on the large screen. And even a minutely detail checklist cannot cover all the possibilities, King said.

Plus a list cannot resolve conflicting corporate goals, like balancing the need to control well construction costs and maintain quality.

The class could be used as an instruction manual for appraisers looking for warning signs of wells likely to require costly work down the road. Signs of a culture that is not supporting long-term well performance include poor completion methods, long strings of casing with little cement, older wells with little or no maintenance, groups of wells with similar problems, like gas pressure buildup, and records lacking well design and maintenance records.

“Those taking on new wells often find the records are incomplete,” he said. In those cases, those wells often “had a lot of things done that are not in the file.”

Those building wells know need to be aware we are in a period of change, and they will need to build wells sound enough to stand up to whatever the future will be. Experience shows it can be done.

“Is there a maximum well life? Probably. But there are some wells over 100 years old and not leaking,” King said.