The run of multibillion dollar combinations of North American oil companies has shifted to Canada with Cenovus Energy buying Husky Energy.

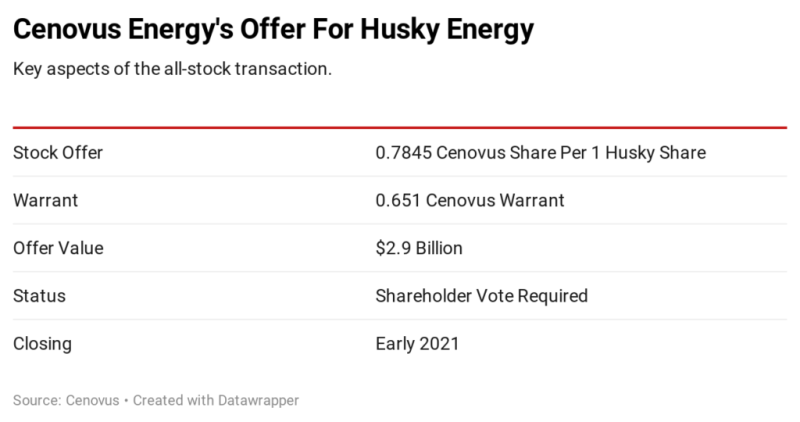

The reasons offered for the all-stock deal valued at $2.9 billion between two heavy-oil companies echoed those recently offered by dealmakers in the shale sector.

Combining companies that have both seen their values drop by nearly 70% this year is expected to save Cenovus $1.2 billion a year, most of which can be realized over the next 12 months, speeding the company’s program to reduce its debt and strengthen its balance sheet.

Savings will come from cutting the cost of running the combined operation by eliminating overlapping management functions—resulting in an unspecified number of layoffs—and reducing the spending needed to maintain production by $600 million annually.

“There will be some [job] overlap in the fields. In this case there will be relatively little more weight on head office functions,” when cutting staff at the two Calgary-based companies, said Alex Pourbaix, chief executive officer for Cenovus.

This combination is expected to reduce the breakeven cost for the expanded Cenovus to $35/bbl in 2021 and $33/bbl by 2023. And it is likely to improve what Cenovus is paid for its oil by acquiring a company with enough spare processing capacity to turn low-cost heavy oil into higher-value oil or other products.

The deal appears to be a logistics dream come true. Cenovus produces 225,000 BOE/D more than it can process and Husky processes 135,000 BOE/D more than it produces and also has the pipeline capacity to deliver that oil to US markets where it is worth more.

For years, Cenovus’ revenues have been reduced by the low benchmark price of heavy Canadian crude—Western Canadian Select—because it lacked the facilities to upgrade the bitumen produced by its oil sands operations, whose price was depressed by the lack of pipeline capacity out of Alberta.

“Obviously one of biggest challenges for our company” has been the large amount of heavy oil it had to sell for the low prices offered in Alberta, Pourbaix said, adding, “We really admired the integrated business model, but for most of the time there wasn’t an opportunity to acquire refining.”

That changed this year with oil demand weak and likely to remain so for another year or so, reducing the price of the deal and making it possible to pay in stock rather than cash.

One detail that distinguished this deal from others recently was the 21% premium paid to Husky shareholders, who also received a warrant giving them the right to buy more shares at a price based on recent trading.

Pourbaix said the high premium was the result of price changes in the shares after the deal was reached.

Also, the supply of companies offering what Husky can offer is extremely limited. This deal will create the third-biggest oil producer in Canada and its second-largest refiner. It shrinks the small, mostly Canadian group of companies in the oil sands business, so the potential for further deals is limited.

Analysts welcomed the cost-cutting message which could speed Cenovus’ path back to an investment grade rating for its bonds. And it inspired them to ask how Cenovus will cut costs further or bring in cash with asset sales.

The answer was yes, but those things will take time.

Cenovus has begun looking at how to integrate its major oil-sands operations with Husky’s huge Lloydminster upgrader. That will add value by turning low-value bitumen into high-quality refinery feedstock, but the cost of the upgrades needed to do that means any such change is years off.

The predicted savings do not include any asset sales, though the presentation showed the combined company could sustain its 750,000 B/D level of crude production by spending $2.4 billion per year compared to $3 billion for the two companies. This suggests they are holding more oil properties than they need in a slow- or no-growth business.

Analysts pressed management on whether it will be backing away from two big ventures, the White Rose West project, aimed at expanding production offshore Newfoundland—which was recently put on hold through 2021—or its extensive gas reserves in western Canada.

Both projects are in depressed sectors which make them logical divestiture candidates, but for the same reason, they are not likely to draw an offer that would motivate management to sell.

Pourbaix said Cenovus “would retain an open mind” if an attractive price was offered.