At some point during the first half of this year, Colombia replaced politically and economically crippled Venezuela as Latin America’s third-largest oil-producing country.

That put Colombia behind only Brazil and Mexico in the hydrocarbons-rich region, two nations on divergent paths in terms of oil flow. Since Brazil ended state-owned Petrobras’ monopoly and opened up its industry to international companies in the late 1990s, the country’s oil output has almost tripled as it found and tapped into its giant offshore presalt fields. Output from Mexico’s state-owned Pemex, meanwhile, has fallen to its lowest level since at least 1990, and President Andrés Manuel López Obrador is working to stymie energy reforms implemented in 2013 to rejuvenate industry in the country.

With the lessons of its resource-rich neighbors in mind, Colombia finds itself in a similar position where it must carefully choose a path forward for its industry or risk squandering great potential, or worse, losing what took years to build. The Andean country in the early 2000s overhauled its regulatory framework, reduced government take, and held licensing rounds with the intent of attracting foreign investment. Oil production subsequently rose to more than 1 million B/D before dropping amid the global industry downturn. Output in May averaged just short of 900,000 B/D.

The Colombian government is trying to build on the foundation established by those reforms by implementing a novel permanent, continuously open bidding process and exploring unconventional development. The aim is to replenish depleted oil and gas reserves and increase production. Based on its 2018 output, the country’s crude reserves are good for just 6.2 years, while its natural gas reserves would last 9.8 years, falling below the 10-year mark for the first time in decades, according to statistics from Colombia’s National Hydrocarbons Agency (ANH).

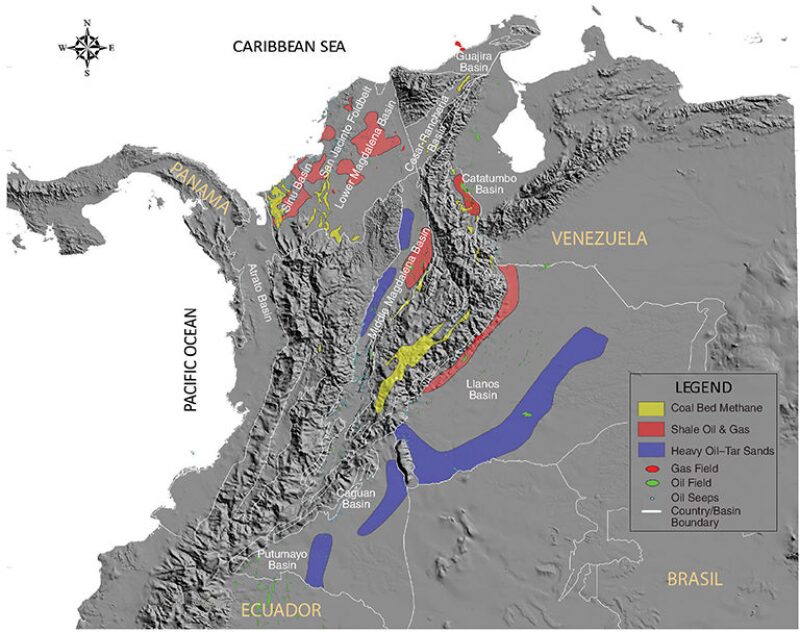

But Colombia has long been seen by the global industry as a petroleum province with upside that surpasses just incremental reserves and production gains. All of its liquids and nearly all of its gas production is extracted conventionally onshore, meaning its offshore and unconventional sectors are nascent. Colombia, which shares a more than 2000-km border with Venezuela, has proven petroleum systems that have produced oil and gas for a century, and the application of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing offers huge promise.

María Fernanda Suárez, Colombia’s minister of mines and energy, has said that unconventional development could triple the country’s oil and gas reserves. Standing in the way, however, has been public resistance to hydraulic fracturing, and pilot projects that would demonstrate its benefits are yet to get environmental approval. There is “game-changing potential—if the industry can get going with development,” said Ruaraidh Montgomery, research director at oil and gas research firm Welligence Energy Analytics.

On the other side of Venezuela sits Guyana, which has scored a bounty of oil through more than a dozen offshore discoveries by ExxonMobil since 2015. Colombia’s offshore potential is less clear given the presence of only one producing field in the country’s history—Chevron’s shallow-water Chuchupa field, which has been flowing gas since 1979. But deeper wells drilled and seismic data collected since the reforms of the early 2000s have improved knowledge of the region’s geology, leading to four gas discoveries and suggesting liquids potential.

Reeling Back in the Majors

Advancing participation in its offshore sector, ANH this year has awarded blocks to ExxonMobil, Shell, Repsol, and Colombia’s state-owned Ecopetrol, with Houston independent Noble Energy entering the country via a subsequent farm-in to Shell’s block. Among the longest-tenured international firms operating in Colombia, ExxonMobil has ramped up investment in South America as of late, with major projects in Brazil, Guyana, and Argentina. However, in recent years it has scaled down its Colombia work.

Waning interest in the country from foreign companies, particularly from the majors, caused ANH to rethink how it approached contracts, extending exploration terms to give firms more leeway in their commitments. ANH then rolled out its new permanent licensing scheme in which prequalified firms can bid on offshore and onshore blocks not formally on offer in licensing rounds.

A benefit for the foreign firms targeting Colombia’s offshore is its low cost of entry. “It’s not like Brazil where you’re having to put down a lot of dollars to get exposure to acreage,” said Montgomery. “But Brazil is proven—the presalt is a world-class resource, so you have to pay to get access.”

Risk is mitigated through technical evaluation agreements (TEAs) that allow companies to carry out technical studies over large swaths of unexplored or underexplored acreage without making expensive work commitments. If those firms wish to proceed with drilling, they can negotiate the acreage into an exploration and production (E&P) contract with well commitments.

E&P contracts function under a sliding-scale royalty that varies depending on oil price, crude gravity, and production level. The royalty starts at 8% and increases to 20% at a mid-sized asset—for example, an asset that produces around 20,000 B/D—and tops off at 25%. In the licensing rounds, the bidding variable is usually additional work commitment and sometimes an additional royalty bid. Colombia’s corporate income tax rate is 33%, which will gradually be reduced to 30% by 2022 under the administration of President Iván Duque.

“In terms of a comparison with the rest of the region, we consider the terms appropriate for an established oil province that offers moderate resource potential and relatively low geological risk onshore,” said Montgomery. “There are better terms available elsewhere, but those typically reflect the fact that the exploration risk or cost is a lot higher.”

Alejandro Mesa, who leads Baker & McKenzie’s energy law practice in Bogota, believes Colombia “could still do better” when it comes to the corporate tax rate. However, he noted the government has not rescinded contracts with foreign oil and gas companies and has taken further measures to protect foreign investment. “I think that’s definitely one of the drivers for companies to still look at Colombia,” he said.

Caribbean’s Geologic Appeal

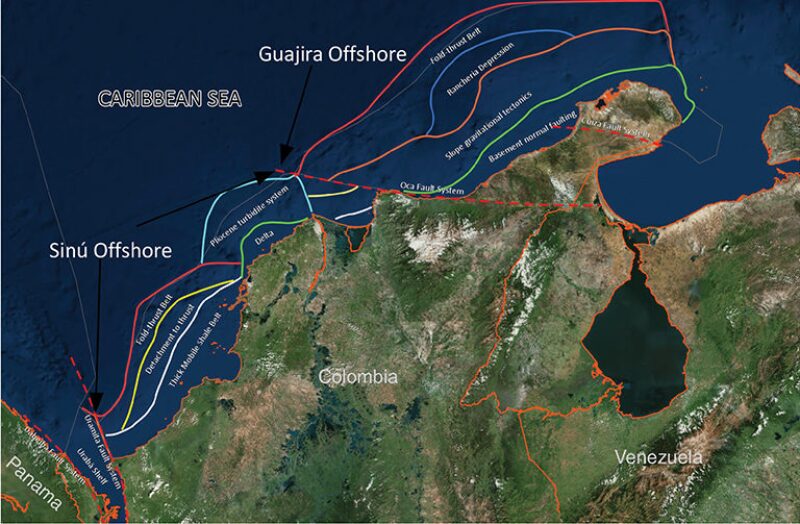

Colombia’s efforts to jumpstart its offshore sector beginning in the mid-2000s first bore fruit in 2014 when Brazil’s state-owned Petrobras made the deepwater Orca gas discovery in the Guajira Offshore Basin. Then, during 2015–2017, Anadarko made the deepwater Kronos, Gorgon, and Purple Angel gas discoveries in the Sinú Offshore Basin. Anadarko has since relinquished its interests in those blocks, and Ecopetrol hopes to farm out stakes as it moves toward appraisal drilling and formation testing. Petrobras plans to drill another well near Orca in 2020.

Those discoveries confirmed a working petroleum system in Colombia’s deep waters. Enticed by the presence of oil seeps from the continental shelf and adjacent onshore basins, foreign operators in the coming years are likely to turn their attention to finding liquids deposits in the region, including Noble, which is slated to drill an exploration well next year.

The Colombian Caribbean’s newfound geologic appeal comes from “compelling evidence” that the subduction active margin model previously accepted by petroleum geologists in the region “might not be the best explanation for the evolution of the Caribbean margin and its prospectivity,” explained Roberto Aguilera, founder and president of RA Geologia, a Bogota-based geological and geophysical consultancy.

In the past, some operators accepted that model and gave up on the area “because of the risks associated with trap integrity and reservoir quality,” said Aguilera. “But other companies and people studying the area started to propose alternative interpretations for development of the margin and its prospectivity based on the new 3D seismic, geophysical, and geochemical data acquired during TEA evaluations.”

This new data suggest that the margin has more passive-like behavior, with deformation in the southern basins mainly caused by mud diapirs and extension associated with mud withdrawal and gravity sliding, creating folds and minibasins similar to those found in the Gulf of Mexico and Caspian Sea. This in turn produced a deformation front toward the continental slope of toe thrusts where Anadarko and Ecopetrol made their recent gas discoveries.

While the more established Gulf of Mexico and Brazilian margins and the freshly tapped Guyana margin are each passive, there are key differences between them and the one in the Colombian Caribbean, he noted. Those differences include the Colombian Caribbean margin’s extensive mud diapirs instead of salt diapirs, uncertainty related to its pre-Tertiary rock, and the apparent gassy nature of its petroleum system vs. the liquids discoveries of the other offshore basins—and even compared with other mud-diapir basins such as the Caspian Sea.

There is still much to be learned about the Colombian margin, however, so comparing it with more-established basins is currently difficult. “But it will probably have the best of both worlds,” Aguilera said.

Familiar Foreign Operators

With age comes wisdom for Colombia’s onshore fields. Unlike offshore, there is now a century’s worth of onshore E&P knowledge dating back to the historic La Cira and Infantas oil fields in the Middle Magdalena Basin in the north-central portion of the country. Most of the country’s oil and gas production since the industry’s inception there has come in the Middle Magdalena.

One of Colombia’s most active foreign operators, Occidental Petroleum, gained a stake in La Cira-Infantas in 2006 and is operator of the Caño Limón field, located in the northern Llanos Basin, that started oil production in 1985. Chevron since 1977 has been producing gas from the onshore Ballena field, which is near the shallow-water Chuchupa field, in the onshore Guajira Basin.

New onshore exploration and application of new recovery methods are needed to offset declines from these aging fields. The good news for Colombia is that its relative openness to participation from foreign operators over the past 5 decades has allowed capable, innovative international producers such as Chevron and Oxy to gain a better understanding of the country’s onshore geology and sociopolitical environment that includes decades of civil unrest.

Oxy in particular has been “gradually stepping up” work on its existing assets as well as positioning itself “for new growth opportunities,” said Montgomery. The company has added several blocks during the last couple of years and in 2018, alongside Ecopetrol, sanctioned a steamflood project for the mature Teca heavy-oil field, where production is expected to reach 30,000 BOE/D by 2025 and break even at West Texas Intermediate oil prices of less than $40/bbl. But how Oxy plans to proceed in Colombia following completion of the Anadarko acquisition will remain to be seen.

Meanwhile, small-to-midcap independents such as Canacol Energy, Gran Tierra Energy, Parex Resources, Frontera Energy, and GeoPark have successfully exploited conventional oil and gas in Colombia in recent years and resemble the nimble producers that fueled the US shale revolution. “Colombia has been very successful at bringing in investment from that type of company” since the fiscal and contracting reforms of the early 2000s, Montgomery said.

Ready To Frac, but When?

But the bad news for those hoping for an imminent and rapid launch of an unconventional revolution in Colombia is that the hydraulic fracturing debate there mirrors that in the US. Politicians have seized the issue as a means to criticize the Duque administration, and some citizens have developed a negative perception of the practice before it has even had a chance to be demonstrated for unconventionals. “The government has a lot of work to do to win the battle for hearts and minds to really move forward with this, because [it needs] the support of local communities especially,” Montgomery said.

Colombia’s identity is in its diverse native population and environment, Mesa explained, and preserving both is paramount. Perception that either could be negatively affected is often met with fierce resistance—courts, for example, are known as ardent protectors of community rights. While companies may view this as an obstacle, Mesa said, “I think right now everybody understands this is part of the game—that you have to engage with communities, you have to engage with groups that are affected by the oil and gas activities.”

“Overall, when looking at oil and gas, even if it’s just conventional, there are ongoing community tensions, there are blockades that happen,” said Elena Nikolova, Latin America upstream analyst at research consultancy Wood Mackenzie. “But unconventional production also has a very different surface footprint. And for Colombia, it’s really going to be key to figure out how to maximize shale potential with a minimal footprint.”

The Middle Magdalena Basin, which lies in a river valley between the Andes’ central and eastern mountain ranges, is not like the Permian Basin in the US or Vaca Muerta Shale in Argentina, where there are wide-open, relatively flat spaces. And, for unconventional development, said Montgomery, “The infrastructure is just not there. Traffic is going to be horrendous” due to the equipment, supplies, and personnel needed once the service sector finally builds up to capacity.

To encourage more transparency with fracturing activity, the Duque administration last year established a commission to carry out a comprehensive review of the stimulation practice in Colombia and make recommendations as to whether it can be done with minimal interference to the environment and local communities. Earlier this year, the commission endorsed fracturing pilots but said the projects must be closely monitored.

However, Reuters reported in April that an environmental application for a pilot submitted by Ecopetrol had been shelved. Late last year, partners ConocoPhillips and Canacol were denied environmental approvals for two pilots on separate blocks in the Middle Magdalena Basin. Charle Gamba, Canacol president and chief executive officer, said during his company’s first-quarter earnings call in May that if the partners were to resubmit the permits, it would likely take another year to get approval and then another year-and-a-half to mobilize stimulation equipment from the US.

Those pilots would have been crucial to proving that fracturing works technically and can be done without negatively affecting its surroundings, Mesa noted.

If similar projects are to be approved, “it’s probably going to be Ecopetrol to lead the way in terms of large-scale investments,” Montgomery said, as Colombia’s native oil and gas company would probably have an easier time carrying them out. Ecopetrol has been in the US studying its shale plays—it recently teamed with Oxy on a Permian joint venture—and previously said it was targeting a half-billion dollars in spending on Colombian unconventional pilot projects during 2019–2021. “They’re ready to start testing what they’ve got,” he said.

Colombia needs to replace production soon, and unconventionals, though still possibly years from yielding significant volumes, provide the country’s only real near-term growth potential. “There’s a certain inevitability that they will have to, at some point, produce from it,” said Nikolova.

How Colombia’s Unconventional Basins Compare

Most of Colombia’s unconventional focus is on the Middle Magdalena Basin. Wood Mackenzie estimates the basin’s unconventional potential at 225 billion bbl of oil in place with 1.3 billion bbl recoverable, and 425 Tcf of gas in place with 3 Tcf recoverable. Both estimates assume a relatively low recovery factor of 2% that could increase if production ramps up.

The Middle Magdalena contains the Cretaceous La Luna formation, a deep marine shale mixed with marl and limestone like the Eagle Ford and Niobrara Shale plays in the US.

The La Luna there has oil-prone marine source rock with a good-to-excellent range of total organic carbon (TOC) found 9,000–10,000‑ft deep. The TOC average across the entire interval, which is close to 2,000-ft thick, ranges 2–6%. But some individual beds reach 12–14%.

“It’s really a world-class source rock,” said Julie Francis, an analyst in Wood Mackenzie’s unconventional upstream research group. “It’s richer than what we see in the Eagle Ford” and in the Permian’s Wolfcamp Shale, she said, adding that “one of the great advantages is that it’s very overpressured,” even in the oil zone.

Decades of drilling and production in the Middle Magdalena mean operators benefit from having existing data and cores while not having to prove up the basin through exploration. This experience includes a few vertical wells flowing back from fractured limestone and shale in the La Luna before operators began examining the Middle Magdalena’s unconventional potential.

However, there are several challenges in unconventionally developing the Middle Magdalena. First, fluid types vary across the basin, and understanding which fluid is where in the source rock is not as easy as in the Eagle Ford, where “the depths are on a nice slope with a very simple oil, condensate, and gas window,” Francis explained. Deposits in the Middle Magdalena are found in anticlines with “a fair amount of faulting,” she said, which requires seismic imaging so the operator can determine how to orient the wellbore relative to the fault.

Another source of uncertainty revolves around possible stacked-pay potential. Beyond the La Luna, operators will have to figure out whether the Simití and Tablazo formations can be developed into a larger section.

Next to the Middle Magdalena is the Catatumbo Basin, which is the southern extension of Venezuela’s Maracaibo Basin. The La Luna is also present in this “really rich but really small” basin, she said, where production is “a bit quiet these days” given instability at the Colombia-Venezuela border. Francis believes unconventional development of Catatumbo will be “a little harder because the geologic structures are more complex but also because of the security issues.”

The more gas-prone Llanos Basin contains the Cretaceous Gacheta formation with source rock shales that are similar to the La Luna. The Gacheta interval is thinner and deeper than the La Luna in the Middle Magdalena, with a 600-ft-thick organic-rich section around 13,000–16,000-ft deep, and overpressure also is not as strong. The most prospective portion of the Llanos is on its western edge near the mountains where there is more structural complexity.