Iraq is producing oil at record levels this year but low oil prices have cast doubts on the economic feasibility of its licensing contracts, which some analysts and policy advisers say are holding back higher output.

International oil companies (IOCs) in Iraq operate under cost-plus contracts that require them to make upfront investments before seeking government reimbursements and a per-barrel fee for their profit. This model has enabled the country to reach a new production benchmark of 4.8 million B/D—an achievement diminished by the fact that Iraq’s export revenues have plummeted by more than two-thirds in the past 2 years. As a result, reimbursements owed to the IOCs have ballooned from around 10% of the national budget to 25%.

Luay Al-Khatteeb, executive director of the Iraq Energy Institute and a fellow at the Columbia Center on Global Energy Policy, said both the government and the IOCs failed to prepare for the consequences of a possible downturn in the industry when they entered into the contracts in 2009–2010.

“They were signed on the basis of high oil prices and were very much technical service contracts with no risk-sharing aspect to them,” he explained. “So everything is being paid by the government, and because high oil prices helped in accommodating such huge repayments, the IOCs in general accepted that.”

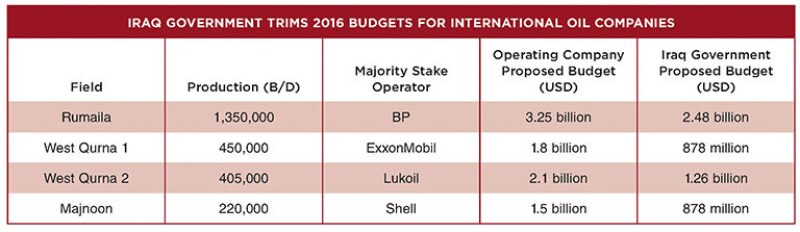

In response to its cash flow problems, which include a costly war, the government has held off on funding major infrastructure projects and ordered IOCs to reduce their spending programs.

These decisions may limit the ability of IOCs to deliver any new supplies of crude while they are still waiting on billions of dollars from the government. Last year, the government paid USD 9 billion in arrears to IOCs for work done in 2014. This year, Iraq must make good on another USD 3.6 billion in arrears, according to the terms of a new loan agreement it secured with the International Monetary Fund.

As an adviser to the Iraqi parliament and the prime minister’s office, Al-Khatteeb is recommending that new licensing rounds be issued with production-sharing agreements or tax royalty contracts to drive higher output from the areas operated by IOCs.

Such contracting arrangements are known as the gold standard in the industry because they share more of the upside with IOCs on the sale of the oil—typically resulting in them using more production-boosting technologies. BP and Shell formally requested the government to convert their contracts into production-sharing agreements last year.

Al-Khatteeb said that doing so will be necessary to achieve Iraq’s ambitions of bolstering crude exports, given OPEC’s historic shift away from its chartered role as global price stabilizer.

“The quota system within OPEC is very much collapsing,” he said. “Everyone is competing for market share now and we have seen that over the past few months—through the disruptions in Canada and Nigeria and other places in the world—that if anything happens like these scenarios in the future, Iraq will need to be ready to replace that loss in production.”

Mixed Expectations

Despite the challenging outlook, the government’s official goal remains to pump out 6 million B/D of oil by 2020—a figure that has been subject to downward revisions before.

Iqdam Hashim Al-Shadeedi, the director general of reservoirs and fields for the Iraqi Ministry of Oil, said it is a “realistic target” but acknowledged that security issues and sharply reduced oil revenues are holding back progress “at a very large scale.”

Included among the delayed infrastructure projects, he said, are the plans to purchase more processing equipment for desalting and dehydrating Iraq’s wet oil.

None of the deferred work is seen as more critical than a long-awaited seawater injection facility needed for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) operations in Iraq’s southern fields. Originally slated to be up and running by the end of 2013, Al-Shadeedi said the 12.5 million B/D water injection project may not be completed until 2019.

“We are now working on other alternatives,” he added. “For example, we are taking water from the subsurface and we have a good opportunity to get the quantities needed for many of our major fields.”

If these smaller-scale EOR projects prove to be a success, and “if we are lucky” to see a sustained rally in oil prices, then Al-Shadeedi said he is optimistic that Iraq can make up for the widening production gap and reach 6 million B/D by 2020.

More Issues

The failure to build the water injection facilities has raised concerns that many of Iraq’s brownfields will not have enough pressure to sustain high production. The only option left is to drill new wells, but Iraq’s turnkey drilling contracts will make it difficult for IOCs to stay within the margins.

Moath Al-Rawi, chairman of Henri Poincare Associates and a former chairperson of an SPE section in Iraq, said the contracts essentially make the IOCs service companies, which is why drilling operations in Iraq routinely suffer from cost overruns. “And once you spend 2 or 3 days extra, the price can increase exponentially and then it’s not economic drilling anymore,” he said.

In the past, there may have been expectations that IOCs would use high-end technologies that could drill wells faster. Al-Rawi said that the exact opposite has happened.

“It doesn’t work that way,” he said. “The economics for an oilfield service company are completely different. They look at the well and say, ‘How many days am I going to spend to construct it?’ They don’t care about the production or when it will come in.”

Mohammed Al-Jawad, professor and head of the department of petroleum technology at the University of Technology in Baghdad, also expressed criticism about Iraq’s IOC contracts, which he said are built on outdated financial laws that are incompatible with modern oilfield business practices.

“For example,” he said, “if a company needs to bring their tools, they have to pass through the normal customs regulations.” Red tape issues like this are often said to be a major factor behind the lack of advanced technologies being used in Iraq.

Al-Jawad raised other concerns over the issues between the Iraqi government and the IOCs, which he sees as hampering efforts to boost local content. He said the country still lacks the modern training centers and research laboratories that have helped other petrostates foster domestic talent.

Al-Jawad said IOCs have been reluctant to hire qualified domestic field workers and professionals despite the fact that “there is an appreciable number of graduates who do not have jobs and are keen to work anywhere in Iraq with a salary much less than those non-Iraqis get.”

Kurdistan Independence

The ongoing row between the Iraqi government and the semiautonomous Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) based in the northern city of Erbil is adding to the uncertainty over Iraq’s upstream prospects. Last year, the KRG ended oil sales through the state-run accounting system and began making its own crude shipments to foreign buyers through Turkey. The federal government responded by holding back funding to Kurdistan, which is fixed at 17% of the annual budget.

The regional discord reached a peak several months ago when Kurdish leaders floated the idea of holding an independence referendum by the end of this year. Most of those familiar with the political situation in Iraq saw the announcement as an empty threat since the KRG has held the same position for more than a decade.

But if Kurdistan seceded, the assumption is that the Iraqi government would be forced to double down on the southern fields in order to make up for Kurdistan’s output, which is around 550,000 B/D this year.

“If this [production] disappeared from the picture, leaving the returns of Baghdad in a shortfall, it has to be replaced by another source and this can’t be done only through developing new fields. It is a lengthy process,” that would take a minimum of 2 years to ramp up, Al-Rawi said.

The KRG has said it is ready to resolve its differences with federal officials in exchange for a monthly payment of USD 1 billion—a figure it believes equals its promised 17% share of the budget, but that may be untenable due to the ongoing cash shortfalls.