From 2007–2010, I was president of Chevron’s Environmental Management Company. We were responsible for managing end-of-life activities and environmental liabilities for the entire corporation. We removed platforms and pipelines in the Gulf of Mexico, remediated old industrial sites (including refineries, chemical plants, and service stations), and managed Chevron’s Superfund liabilities. Chevron spent several hundred million dollars a year on these activities, all with zero return, which made for uncomfortable discussions when it was time to present my budget.

Decommissioning yields no return on investment or revenue and carries significant environmental and regulatory liabilities. The effective decommissioning of offshore platforms, subsea wells and related assets is one of the most important challenges facing the oil and gas industry today and in the future. Decommissioning decisions can no longer be avoided by the operators and the industry as a whole.

Decommissioning and abandonment. That was a Technology Focus topic in the January JPT, and I loved the featured quote: “Unlike a capital project, decommissioning is not something that you can choose to do or not to do.” Like death and taxes, decommissioning eventually comes for every project. The question is: Are we operationally and financially prepared for the inevitable?

The offshore decommissioning problem is huge and gets bigger every year as more platforms reach the end of their productive life. North Sea decommissioning is leading the way as fields developed in the 1970s and 1980s reach their end of life. Created 7 years ago, Decom North Sea is an industry association that specifically addresses the decommissioning issues in the North Sea and works cooperatively among operators, regulators, and decommissioning contractors. The North Sea regulators, especially UK and Norway, recognize the growing liability.

Decommissioning Gulf of Mexico facilities got much more urgent following hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005; they swept right through the heart of the aging continental shelf fields of offshore Louisiana. Katrina and Rita destroyed more than 100 offshore platforms, many of which were “idle iron,” not in service pending decommissioning. Following those massive storms, US and state regulators stepped up monitoring of shut-in platforms and began pushing operators to decommission and remove idle iron before the next major hurricane.

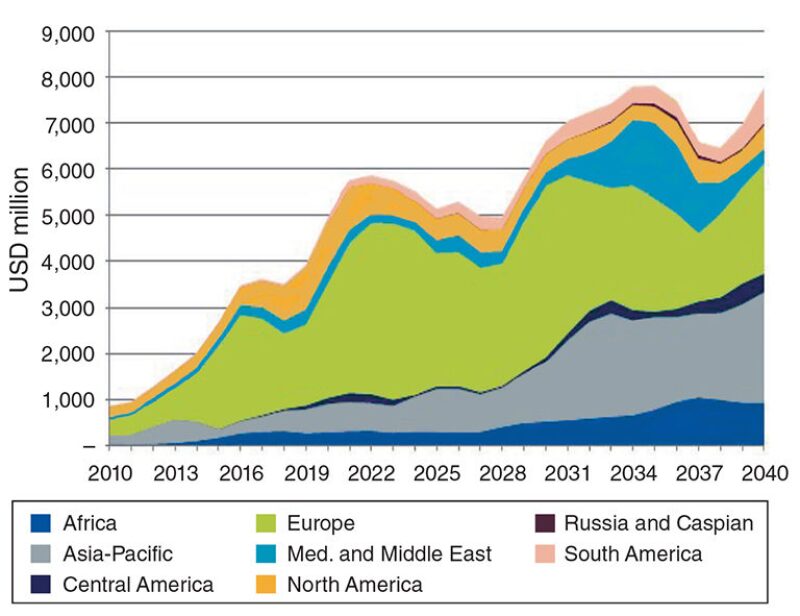

So how big is the problem? The industry consultancy IHS Markit released its Offshore Decommissioning Study Report in November 2016, and its estimates of future spend are stunning, according to this graph. IHS estimates that USD 2.4 billion will be spent on offshore decommissioning of over 600 installations between now and 2020, over half of that in the North Sea and most of the rest in the Gulf of Mexico. Between 2021 and 2040, USD 13 billion will be spent to decommission more than 2,000 installations; that work will expand to other aging offshore regions such as West Africa and Southeast Asia.

Not a penny of that generates revenue for the operators.

As an additional data point, the latest decommissioning report published by the industry cooperative Oil and Gas UK estimates that—through 2025—GBP 17.6 billion will be spent on decommissioning along the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS). Last year, GBP 2.1 billion was spent on offshore decommissioning in the UK and Norway. Decommissioning is estimated to be 12% of total UKCS spend in 2017—and growing.

And that’s just offshore. These estimates don’t include onshore decommissioning, plugging and abandoning, facilities removal and site remediation, including wells, pits, tanks, and pipelines and gathering systems. In longtime onshore producing regions such as Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana, the potential cleanup and removal liabilities are staggering. Cleanup and remediation of past production and drilling pits alone could measure in the billions of dollars. Most of our liabilities, especially onshore, preceded environmental regulations. It was just how things were done in the oil industry as well as in most industrial projects such as manufacturing and military operations.

So what can be done? It boils down to Risk and Reward, the theme for my columns. When people and companies are rewarded for short-term performance, there is little incentive to deal with long-term risks such as decommissioning and environmental cleanup. It’s so much easier to leave it for the future; but increasingly, that future is now.

Here are some ideas on how to deal with that future.

Clean as You Go

The easiest mess to deal with is the one you never make. In one of those uncomfortable budget discussions with Chevron’s executive committee, someone asked, “How can we avoid this?” My answer: “Keep it in the tank.” My recommendation was that we should clean as we go, as I do when I make Thanksgiving dinner. From the blank stares I got, it was apparent that none of them had ever managed a large dinner party. The key to big party execution is not to leave all the dirty dishes and pots for when the party is over, but to clean as you go, leaving little for the end. We should do more cleaning as we go in our operations, while we have income and infrastructure. Too often, operators hold off until the bitter end, then scramble for resources to finance remediation or sell the field off to a smaller operator, hoping to avoid the decommissioning liabilities. Selling liabilities forward is false security, especially for well-capitalized operators, since environmental or decommissioning liabilities from long-gone can and do come back. If we clean as we go, we don’t leave an unfunded future.

Design for Smaller Footprints and Decommissioning

To steal a phrase from Stephen Covey, “begin with the end in mind,” meaning we should design projects knowing that eventually they will be removed. More companies are including eventual decommissioning and removal into initial project design. Reducing footprint of onshore fields, better life cycle waste stream management, and smaller footprints in general will make future cleanups easier. Using tanks instead of pits keeps contamination contained and forces better waste management. Offshore, projects should keep better records and design platforms with a consideration for decommissioning. A little time and money spent upfront can save many millions in the future.

Innovative Decommissioning and Remediation Technologies

Our industry has a history of innovation through desperation and with the looming overhang of decommissioning costs, it’s looking desperate. The high cost of decommissioning creates business opportunities for technology to cut costs while still protecting people and the environment. Innovative lift equipment has been specially built for offshore decommissioning. New cementing and well monitoring can better ensure that groundwater and the environment are protected. Better project management can streamline operations. New remediation techniques help soil impacted by crude oil or salt water recover faster. Cheaper can be better, especially when it incentivizes operators to clean up more and faster.

Creative Financial Incentives

Many operators avoid decommissioning or remediation because they can’t—or won’t—pay for it. Operators may also decide to abandon a field rather than sell it (and the liabilities) to a smaller operator that could have lower operating costs. To combat this situation, the UK government is experimenting with creative financial solutions not only to keep aging fields producing, but also to plan for plugging and decommissioning. The UK Oil and Gas Authority (OGA) recognizes the coming wave of decommissioning as the North Sea production ages and becomes uneconomic to produce. OGA has published its Decommissioning Strategy, in which it recommends cooperation among the government, industry, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to maximize economic recovery (MER). The MER UK Forum was created by OGA so that it, government, and industry would work together to maximize economic recovery from the UKCS and maximize the UK value from the oil and gas industry as a whole. For aging fields, the MER decommissioning strategy is designed to ensure that industry explores all viable infrastructure options before abandonment, and that decommissioning is executed in balance with the maximization of value from economically recoverable reserves.

OGA is also encouraging creative commercial models for sharing decommissioning liability. With creativity, a large operator can turn over operations to smaller, more nimble operators, while retaining some of the decommissioning liability and oversight over the new operator. A new commercial scheme was recently used in the sale of BP’s Magnus field to EnQuest where future profits and liabilities were shared. Balancing the interests of government, industry, NGOs, and the public, we can work together to create better solutions.

“Decommissioning and abandonment is not something you can choose to do or not to do.” The end will come for every project. Just like the financially smart person includes a will and estate planning in her financial plans, our industry must also plan ahead for the future, which includes the end.

For Further Reading

Thornton, W. 2017. Decommissioning and Abandonment. J. Pet Technol 69 (1): 68–74.

IHS Markit. 2016. Offshore Decommissioning Study Report, (accessed 03 April 2017).

UK Oil and Gas Authority. 2016. Decommissioning Strategy, (accessed 03 April 2017).