Diagnostic testing is beginning to show how a lot of unconventional wells are leaking money.

Sophisticated diagnostic testing programs undertaken by operators Devon and Shell have documented significant potential problems that could have costly consequences.

Measurements taken by Devon of three layers of a stacked formation showed how failure to test to see if production in one zone is pulling oil and gas from another can mean that some zones are missed while others produce far below their potential, according to a paper (SPE 189835) presented this week at the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference.

And when Shell tracked the path of fracturing fluid injections, it found that nearly half the time the injections bypassed the stage they were designed to fracture and went to another stage feeding the growth of troublesomely large super fractures (SPE 189842). The handful of tests by Shell confirmed that the leaks are outside the casing, squeezing in between the cement and the formation.

While the Shell paper was based on its work in single-entry, pinpoint fracturing, where it hits only one spot per stage, other studies have shown it is applicable to widely used plug and perf methods.

“You should be bothered by this. It happens very frequently in plug and perf,” said Gustavo Ugueto, senior staff petrophysical engineer for Shell, who delivered the paper. He said companies need to work together to identify how to drill and complete wells where these leaks are not common. They have also observed wells with no leaks.

“We need to get our heads together and figure it out. It is eating out lunch,” he said.

Devon’s project focused on how to most profitably develop the multiple levels of a stacked play, a widespread problem facing the industry.

“The properties are going for high-dollar amounts (so) we need to optimize” development plans, said Kyle Haustveit, a completions engineer for Devon Energy, who led a project to determine how best to develop three layers in the Meramec formation in Oklahoma.

“This points to a wider industry problem—many wells produce from other layers but the connectivity is not known,” Haustveit said. The risk is that the well will effectively produce from the zone it is in but not the next one over.

In this case, which guided future development in the area, two wells were communicating and needed to be developed jointly, while the top layer was isolated by a layer of limestone and needed to be developed separately.

The one-of-a-kind testing programs were not cheap. They both deployed multiple methods because “no single fracture diagnostic can answer all of the questions,” Ugueto said.

For example, Devon conducted:

- Two kinds of dynamic flow inject tests to see if pressure at one level was likely influenced by other zones.

- Offset pressure measures to see if changes in one well could be detected in another.

- Measurements of the area stimulated using both a proven technology, radioactive proppant, and new one, electrically conductive proppant from Carbo Ceramics, providing a more detailed 3D image showing the extent of the area where fractures were propped.

- A comparison of the findings with fracture models as part of an effort to cross check all the results.

The papers offered evidence of long-standing problems where the findings to date have not been sufficient to provide an economic argument for change.

New Evidence

Another paper delivered during the conference (SPE 189851) discussed the development of a small but growing business documenting where fracturing fluids flow.

EV Offshore takes high-definition pictures of how perforations can be radically changed by the grinding force of high-pressure steams of sand and water during fracturing. As its name implies, onshore is not the company’s focus, but it has been approached by companies with unconventional properties looking for high-definition images that document perforation erosion, as well as an automated process for sorting hundreds or thousands of these images to see which grew and which did not, said Jeff Whittaker, a sales manager for EV, who delivered the paper.

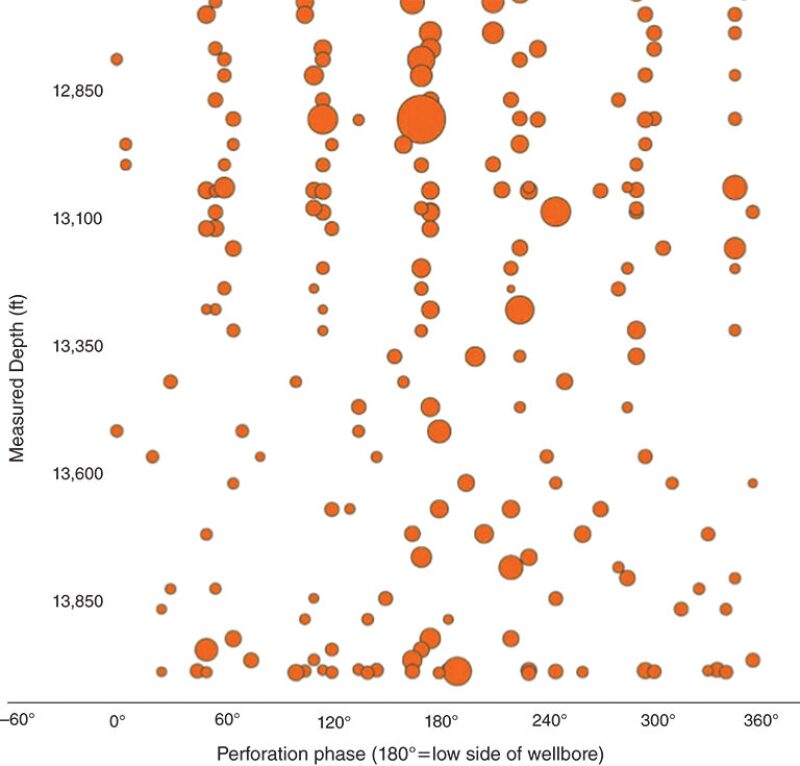

Information on fracturing effectiveness within stages is scarce. EV’s method is based on the assumption that “the more proppant in, the more erosion,” Whittaker said. The implication is “if you see a big hole, that zone is stimulated.”

Perforations taking in the most fluid can quickly grow to 10 times their original size while perforations missed hardly grow at all.

As with any test, it is wise to add other data before drawing conclusions. While erosion shows what has gone in during fracturing, other methods are required to measure what comes out, but these measures can offer ideas on where to look.

An automated process sorts the images, making it is possible to compare the sizes of all the perforations based on their location. For example, ones at the bottom of the well tend to be far larger than those perforated at the top.

While the study showed before and after pictures, in most cases companies do not want to pull equipment out of the well to do the before pictures, even though the perforations created commonly vary based on position of the perforation gun.

EV is working on speeding the process of taking the pictures, which now requires manually moving the wireline into place, allowing about 240 perfs a day to be photographed each day, he said.

Automated sorting by location can offer a data point for those trying to decide if more perforations are a good investment because more rock is stimulated, or are a waste of money by adding more underperforming perforations.