The standard for progress in shale development has been the drastic reduction in the number of days needed to drill a well, from more than 20 to less than 5 in some unconventional plays. But some question whether it has become a misleading metric for an industry needing more productive wells.

“The human tendency is to optimize within a given constraint. Right now, it is reaching the total depth in the shortest time,” said Robello Samuel, technology fellow, drilling, at Halliburton. “If all you care about is that quantification, you do not worry about tool damage or wellbore quality, or what it is like to complete it.” Maximizing drilling performance and efficiency is not the same as optimizing it, he said.

“Everyone needs to remember why they are drilling the hole. As much oil and gas needs to come out as possible,” said Bart Critser, geosteering manager for Terra Guidance. “Otherwise it’s just a multimillion dollar, fancy hole in the ground.”

The payoff for drilling faster has largely been realized. While further time savings are possible, the discounts now offered by service companies hungry for work have slashed the potential savings. In September, the day rate for a typical rig in the Permian Basin was USD 18,000, according to Hart Energy Market Intelligence. That is equivalent to only 360 bbl of oil at USD 50/bbl.

Saving a day of drilling is a bad trade if the hole quality suffers. The downsides of a badly drilled well can range from casing damage and pump breakdowns, to missed sweet spots and accumulations of sand in low spots slowing the flow, according to drilling experts at the recent SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition (ATCE) held in Houston, and in interviews since.

One of them, Moray Laing, oil and gas lead for the SAS Americas Energy Practice, raised a seemingly simple question: “Having good directional control gives you better wellbore quality. I wonder why we are not measuring that systematically?”

No one at the ATCE or since has offered a simple formula to answer that question. The measure of a productive wellbore will vary based on corporate business models and the opinions of exploration and production experts from a variety of disciplines, often with conflicting points of view.

To a geologist, what constitutes a productive wellbore leans toward geosteering to guide the hole through the most productive rock, which can run counter to the goals of a production engineer worried that the ups and downs of a tortuous wellbore will lead to long-term blockages. It is often hard to put a dollar value on some potentially costly long-term side effects of a poorly drilled well.

“The objectives of the departments doing drilling, fracturing, and production are not the same,” said Robert Shelley, director for well performance evaluation at StrataGen, Carbo’s fracturing consulting arm. “Drilling is measuring the dollars per foot. The goals for completions and production are a little more abstract.”

Simple Incentives

There is anecdotal evidence that hasty drilling can reduce productivity later and substantially increase maintenance costs. For example, a US operator recently used SAS advanced analytics to look for patterns in maintenance data, seeking ways to reduce downtime in horizontal wells where rod pumps were rapidly wearing holes through the tubing.

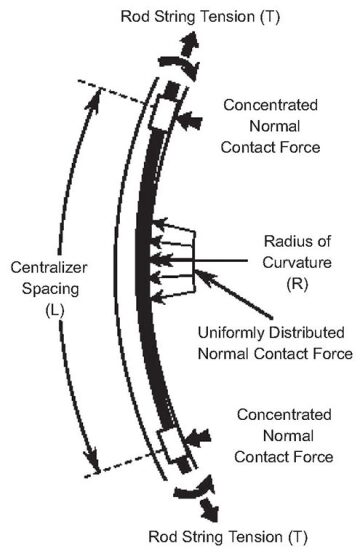

The study showed that the root cause of more than 80% of the tubing failures were curves so tight that the centralizers on the rods could not hold them off the tubing in that dogleg. “The obvious assumption is they drilled too hard, too fast, with too much dogleg,” Laing said.

This case bears a striking resemblance to problems reported 30 years ago in several heavy oil fields in Alberta by C-FER Technologies. The technology development and testing organization also found that tightly drilled curves caused the rod strings driving downhole pumps to wear holes in the tubing, with failures within weeks, or even days.

In both cases, drillers said they were responding to the incentives that rewarded faster drilling. In the 1980s, there were even races, with steak dinner offered to the team that drilled the fastest directional well that day, said Cam Matthews, a C-FER fellow. While crews in shale plays are not competing for dinner, bonus payments are still based on drilling speed.

“We tend to forget what we learned years ago,” Matthews said. “The panic to get as many holes in the ground as quickly as we can is a big factor,” distracting operators from a focus on hole quality.

Drilling has generally slowed compared to the peak of the unconventional boom. Back then, the rate of penetration could exceed the ability of the tools used by geosteering consultants to advise drillers on where the target formation is located.

“I have been involved in a few projects where, as the geosteering specialist, I was at the brink of begging the driller to slow down,” Critser said. “Once they drill over 250 ft/hr, a lot of the high-quality data become useless.”

“The US is not alone in this struggle. In many oil places across the planet, geologists are rewarded for production quality, and engineers are rewarded for speed,” he said. “The struggle between geology and engineering plagues the industry as a whole.”

Engineers are not all on the same side. Those in charge of completing and producing the wells complain about the obstacles they encounter in the wells that they inherit from drilling. “I suspect what we continue to do is we offer no incentive to do anything different, regardless of what happens. That has got to change; it is costing too much money,” Critser said.

Quality Measures

The bottom-line argument for change from Edward Stockhausen, a corporate geosteering and well planning specialist for Chevron known for his ceaseless campaign to better measure and control drilling, is that “proper wellbore position improves reservoir value.”

When corporate earnings are re-leased, though, the focus remains on faster drilling. Recently, Anadarko Petroleum’s chief executive officer (CEO), Al Walker, mentioned the company’s “enhanced wellbore design,” but described its value by discussing how it reduced drilling times and the cost-per-foot by nearly 15%.

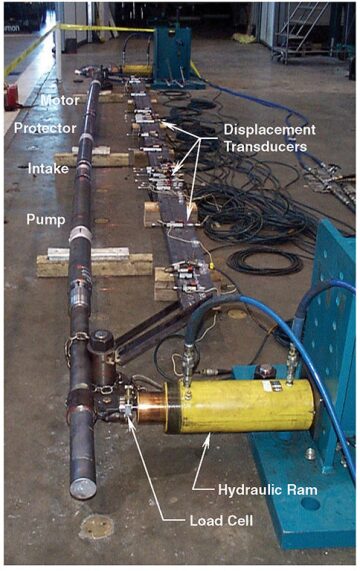

For consultants, wellbore problems remain a steady source of work. Matthews said C-FER has been working on a joint industry project to identify the maximum bend that can be tolerated by an electric submersible pump during installation and operation. The work includes a study comparing the well path promised compared to what was delivered.

Matthews sees a range of drilling quality-management efforts, from large savvy companies with drilling departments that set standards and ensure they are delivered, to small operators whose oversight depends on the skill of the superintendent they send to a well.

Efforts to improve well productivity would benefit if more information was shared on problems and solutions, he said. C-FER is working to put together a joint industry project to collect wellbore and pump performance information in the Permian Basin.

“You have got to keep things in front of people by using data and information from fields,” he said. A wider view can “quantify what you need to do.”

As unconventional explorers have learned that production in these huge formations requires hitting sweet spots, they have adopted tools used in conventional formations to steer through the best rock, such as gamma ray logging tools.

“Clients are trying to drill more precisely,” said Iain Wilson, CEO for GeoSteering. “The [gamma log] tools have been around for 20 years, but innovation is making them cheap and readily available,” which increases their use for unconventional drilling.

Drillers are also being asked to drill longer laterals stretching out 2 miles or more within moving target zones. Devon Energy, which has been involved since the beginning of unconventional development in the Barnett Shale, turned to geosteering several years ago when it began developing the Woodford Shale in Oklahoma, said Bill Wheaton, a production engineer in exploration and strategic services for Devon.

Geosteering had not been needed in the Barnett, which is extremely thick and easily fractured, making precise well paths less critical. In the Woodford, geosteering was required to ensure the well reached the more productive spots.

Devon is one of the bigger companies using analytics to set standards for building and managing wells to increase productivity, Wheaton said. Its drilling control centers put drilling and geosteering experts side by side to balance the sometimes conflicting goals of drilling a relatively smooth wellbore that also comes in contact with the maximum amount of productive rock as it moves up or down.

Critical Conversations

There is no handbook that describes the characteristics of the most productive wellbore. The key performance indicators would need to be defined by the company operating the well, said Fred Florence, president of Rig Operations. “In my opinion, each operator will have their own criteria based on the impact to each one’s bottom line.”

Consultants who work with operators say the first step toward greater productivity is to get those who manage drilling talking to those in completions and production about their definition of a productive well.

“There is a major disconnect between drilling engineers and production,” said John de Wardt, president of de Wardt & Company. The consulting firm advised a company operating in South America to reorganize its drilling operations to increase cooperation among the drilling, completions, and production departments. The result was a 66% reduction in well costs and a 20% rise in production, he said.

Laing points out that the asset managers approving drilling should use that authority to set the standards of the well to be drilled. “It is a two-way street,” de Wardt said. “Those in completions and production need to say this is the product I want delivered to me.”

Geosteering advisers are hired to keep drilling within specific target zones, but Critser said in some cases, they have to elicit specific directions from an exploration team.

“Our company has been asked to steer target windows from 5 to 50 ft,” Critser said. “With a large target window, if the geologist tries to tell us that a borehole anywhere in that zone should be fine, we will try to define a subtarget of about 10 ft and base our target decisions on that.”

“We always get suspicious when a drilling engineer tells us that being out of zone slightly is okay because the fracking will still penetrate the window,” he said.

On the job, geosteering consultants have to translate geologic interpretations of gamma logs into language that the drilling decision makers understand and trust.

In the past year, Gyrodata has adapted its gyroscope-based survey system to create a service called Micro-Guide, which creates a detailed 3D image of the wells based on foot-by-foot measurements after they have been drilled.

These images show features missed by measurement-while-drilling surveys that are usually taken every 90 ft, which tend to offer a smoother view of wellbores. The more detailed images have helped clients diagnose problems, such as early pump failures caused by overly tight turns, said David Moore, a senior account manager and artificial lift placement specialist for Gyrodata.

“These [well evaluations] are really appreciated more by completion and production engineers than by the driller. Actually, it is disliked by some drillers,” said Steve Mullin, director of marketing for Gyrodata.

For completions and production engineers, the data have aided their work by identifying obstructions and providing information to better model the force needed to insert hardware into the well. For the drillers, it offers a detailed critique of their work, showing both the good and the bad.

SPE 22852 Matthews, C. M., & Dunn, L. J. (1993, November 1). Drilling and Production Practices To Mitigate Sucker Rod/Tubing Wear-Related Failures in Directional Wells. Society of Petroleum Engineers. doi:10.2118/22852-PA