The oil and gas industry is facing a progressively more complex work environment that is ever-shifting, less predictable, challenging, multidisciplinary, and increasingly global, with more complicated technical problems to be solved. There is also more public awareness and interest in what we do, how we do what we do, and who we are. Combined with our industry’s rapidly changing demographics, these developments stress the need for development of competencies within a spectrum ranging from emotional intelligence/soft skills to technical skills. In the new work environment, new attributes are rewarded and, although developing technical literacy is highly regarded, the necessity of acquiring soft skills is gaining recognition and is considered equally critical for success.

In an article published in the August 2012 issue of JPT1, the SPE Soft Skills Council discussed the critical need for technical professionals in the future to learn and refine a number of important nontechnical (soft) competencies that have a great impact on the bottom line. With the increasing role of technology and the mixture of social, environmental, political, and economic construct across our industry, the essence of the council’s message was that there is a requirement for finer attunement and shedding of parochial paradigms. This follow-up article introduces a proposed competency matrix as a tool to identify soft skills gaps at various stages of one’s career.

Gaining Importance

Soft skills are about broadening our views and perspectives to enable us to perceive the interdependent nature of our work within our respective organizations and, even more importantly, within a larger social, political, ecological context. By remembering our humanity, we are provided with the possibility to develop sustainable technical and business strategies that consider both the intended and unintended consequences of our solutions. Recognizing the critical importance of soft competencies, Albert Einstein said, “It has become appallingly obvious that our technology has exceeded our humanity.”

A century later, the dominant paradigm about what may be the key for technical professionals’ career success is shifting from technical know-how to an equally or more important soft competencies. Obviously, technical attributes are core to our industry. However, for some years, the quality and strength of human interactions have been increasingly presented as at least equally important in sustaining business success for individuals and their organizations. J.W. Marriott, chairman and chief executive officer of Marriott International, said, “To succeed in today’s workplace, young people need more than basic reading and math skills. They need math skills. They need substantial content knowledge and information technology skills; advanced thinking skills, flexibility to adapt to change; and interpersonal skills to succeed in multicultural, cross-functional teams.”2

This gain in importance of the development of soft skills is fueled by the enthusiasm of the millennial generation of professionals who are rushing to learn a variety of skills before the departure of the baby boomer generation.

Another possible reason for the increasing interest in soft skills, paradoxically, is due to the advancement of technology itself. Advances in computing power, information technology, and processes management in the past few decades have made the technological component of the project’s success so much more reliable that a team’s performance is much less limited by technical possibilities and more by how people work together. By way of a simple illustration, many years ago, the design of an offshore structure required people who could do all the complicated and detailed calculations by hand. That often meant that the key to success was someone with a pocket protector full of pencils who could work a slide rule and perform detailed calculations using multiple complicated nomographs. Today, much of this type of analysis is performed by a computer using finite element analysis and is reliably technically accurate, given that the input assumptions are correct. The inputs, however, come from people and that means interacting with people can become “the problem.” Today, because of the advances in technology itself, complications are more likely to arise from gaps in soft competencies.

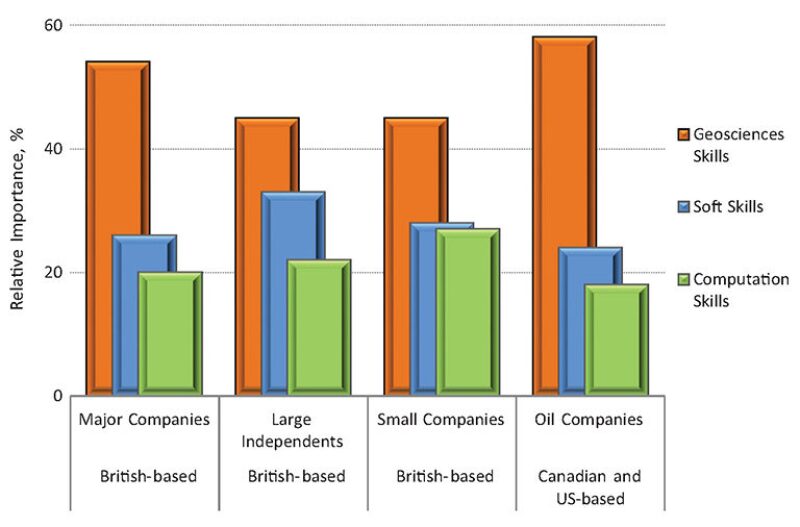

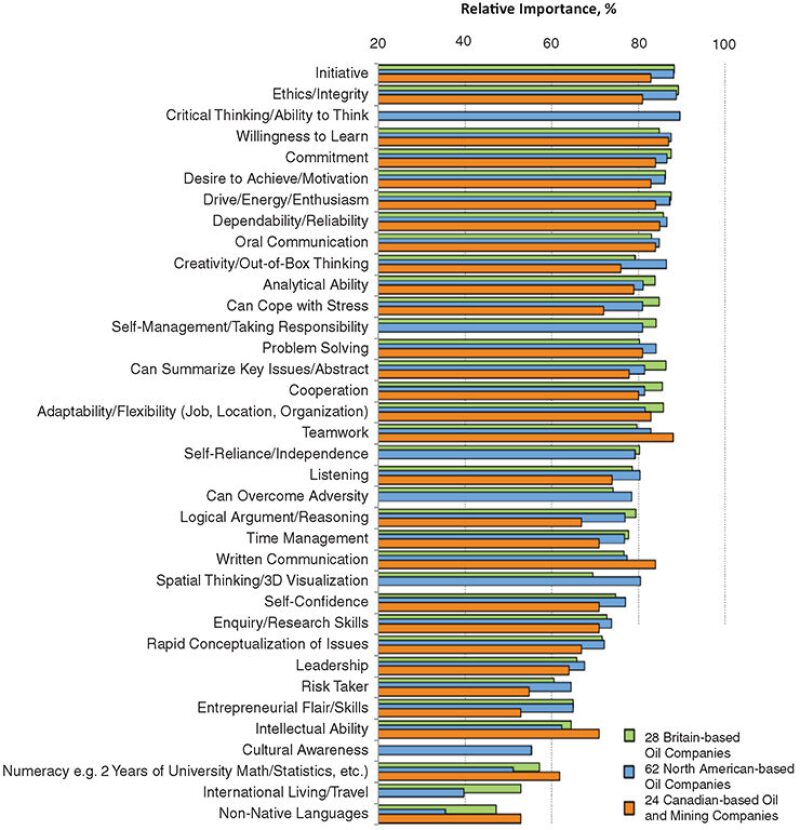

Between 1999 and the early 2000s, a series of surveys3–6 were distributed to about 8,000 geoscientists as a subset of roughly half-a-million employees of a number of British, Canadian, and US companies. The surveys concluded that while the development of the core geosciences knowledge is of primary importance for a strong foundation, acquiring soft skills is more significant to a geoscientist’s career success than the mastery of modern computational/geomodeling skills (Fig. 1). The respondents ranked 36 soft skills by importance. While some differences may be attributed to variations in cultural beliefs, the results shown in Fig. 2 demonstrate a significant consistency among all the companies surveyed. The results clearly indicate that initiative, ethics and integrity, critical thinking, willingness to learn, and commitment are most important to a geosciences technical professional’s career success. The poor showing of global attributes, such as cultural awareness, proficiency in non-native languages, and resilience in international living/travel are surprising for a survey of oil and mining companies that are global by the nature of their business. These surveys were conducted more than a decade ago and a plausible explanation could be that the increasing recognition of the importance of the full spectrum of soft skills in the global arena is a more recent trend.

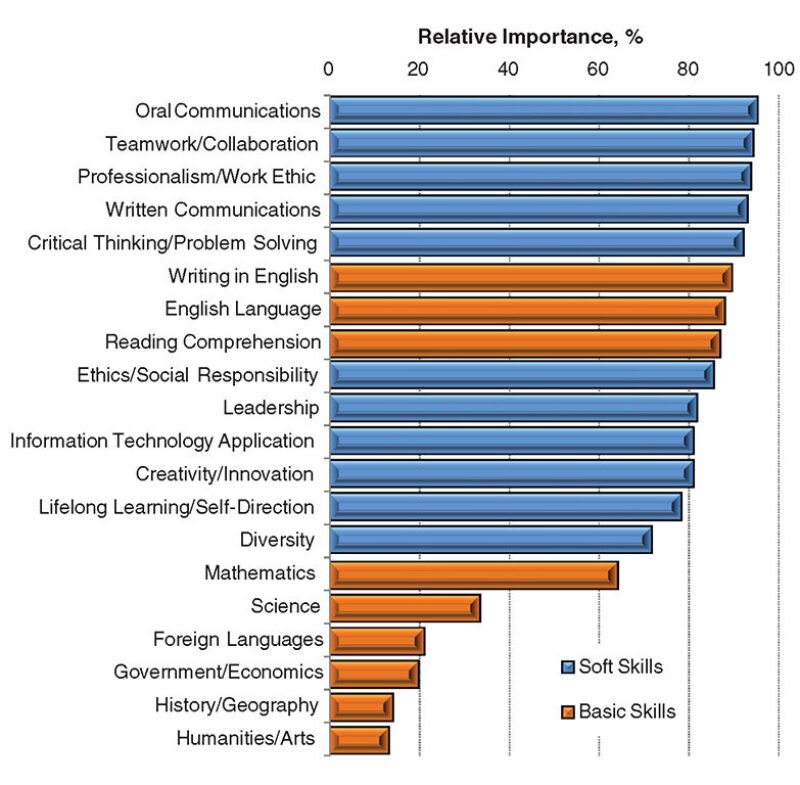

A 2006 study by a group of human resources consultants in collaboration with the Society for Human Resources Management2 highlighted an even more dramatic shift toward the realization of the need for soft competencies. The group surveyed the employees of 431 corporations across several industries (with manufacturing being the largest at about 23%), including the energy industry representing a combined workforce of more than 2 million US-based employees. The respondents were senior vice presidents, managers, and human resources specialists. Employer representatives were asked to rank the importance of 20 areas of basic (core) knowledge and soft skills to the career success of new entrants into the workforce. Fig. 3 shows a comparative ranking of soft competencies and core knowledge. For degreed new hires, it indicates that the soft skills of oral communication, teamwork and collaboration, professionalism and work ethics, written communication, and critical thinking and problem solving occupy the top five most critical ranks.

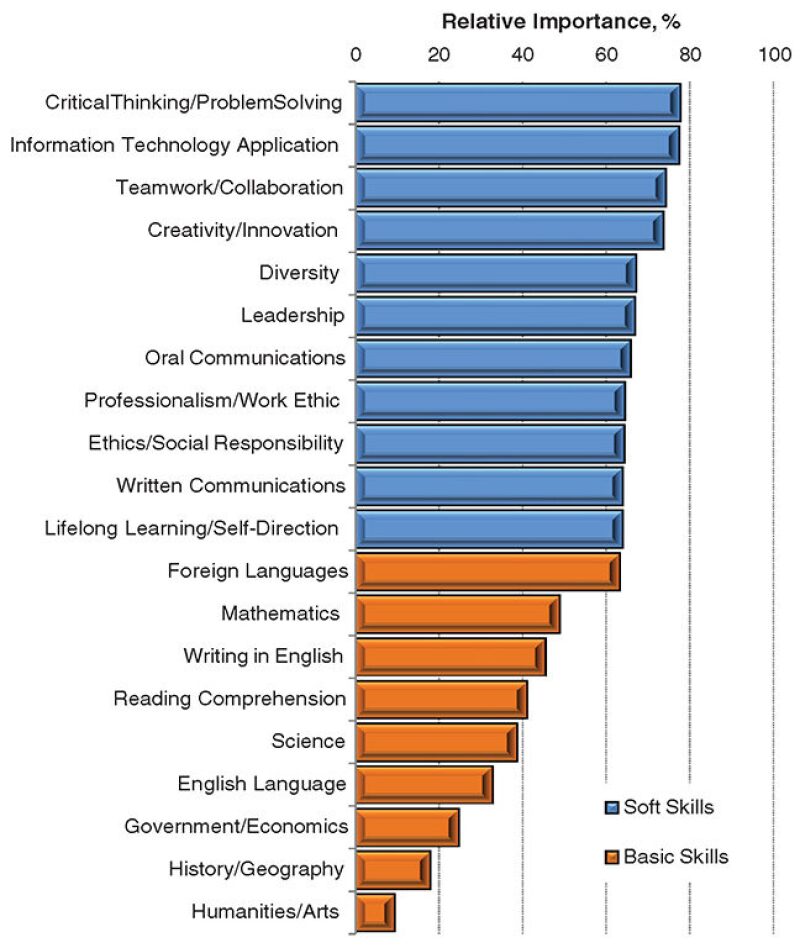

When asked to project the increasing importance of core knowledge and soft competencies in the next 5 years, the group’s response was even more dramatic as shown in Fig. 4. The top five ranked skills included critical thinking/problem solving, information technology application, teamwork/collaboration, creativity/innovation, and diversity. The respondents indicated that soft competencies will increasingly become critical to one’s career success.

An article published on 2 May in the Business Insider7, a US business and technology website, reported that business schools at Notre Dame, Yale, and Dartmouth universities are preparing to introduce testing on emotional intelligence quotient.

Urgency for Petroleum Industry

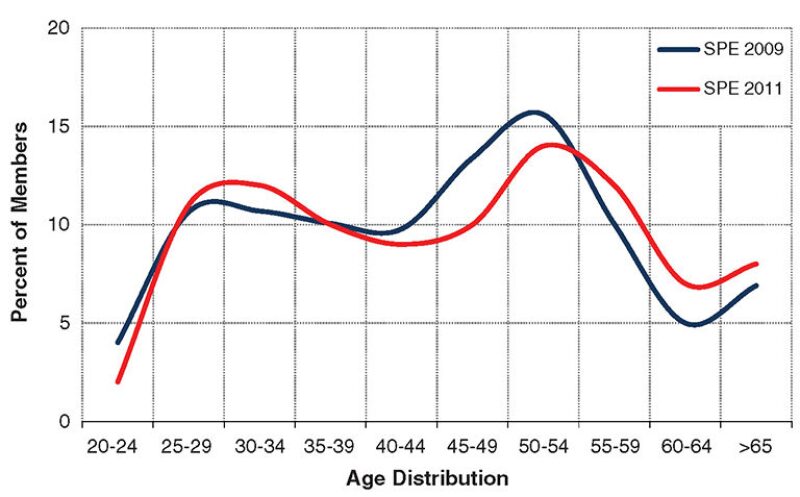

Our industry is going through unprecedented changes as a result of the departure of the baby boomer generation and an increasing demand for energy. This requires attracting and training a new generation of professionals who are entering a global industry. The urgency is to enable them to successfully manage the diversities at the workplace, as well as in the social, political, and ecological contexts that we do business. The age distribution of professionals in our industry is approximately represented by the SPE members’ age distribution shown in Fig. 5. The chart points to the imminent departure of a significant segment of the workforce in the next 5 to 10 years, and that the bimodal nature of the distribution will persist for a few more years. Both in terms of the accelerating pace of departure and the workforce age disparity, the need for the development of soft competencies is critical for the new generation of young professionals.

Interpersonal Attributes

People are often hired for their technical skills, but they fail to advance or their employment is terminated for the lack of well-developed soft skills. Without any guidance on the importance of developing soft skills, the employees with poorly developed soft competencies often fall back on habits previously ingrained through family upbringing, customs, cultural values, etc., which may be ineffective in a professional work environment. Some individuals adjust their patterns of interaction based on feedback and conscious learning experiences, while others are less successful in making the needed adjustment. This unfocused and unclear soft skills learning process is time consuming and generally leads to unsatisfactory outcomes for both the individual and the team. To mitigate this, the SPE Soft Skills Council recommends the creation and use of a soft competency matrix that can increase one’s professional awareness and provide a proactive approach to identifying the gaps and opportunities to address them.

Such a matrix must incorporate the following important elements:

- Progression in people capabilities and actions

- Growth and augmentation of human capabilities with age and experience

- Socio-economic, cultural, and traditional dimension

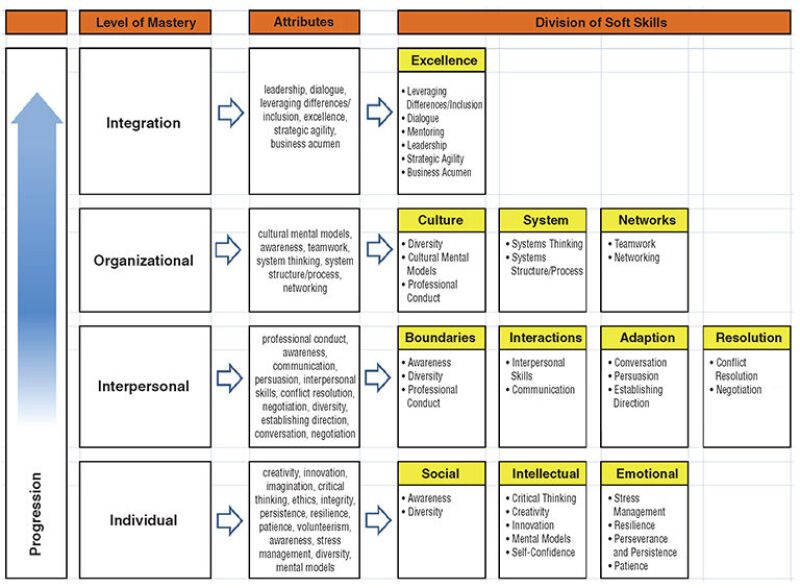

Progression in people capabilities and action. The first element is defined by one’s competency evolution through a hierarchy of levels. It starts at the individual level of mastery of attributes and grows through the interpersonal and organizational, advancing to the integration of all the soft competencies at mature career levels. These levels of mastery and attributes are shown in Fig. 6. This element describes the simultaneous framework of human interaction in any system: the core beliefs and patterns of interaction. It determines how we interact with others, which in turn determines how we engage and view the larger systems, and integrate and leverage our core technical and business skills.

Growth and augmentation of human capabilities with age and experience. The second element is related to time-in-career, defining the stages in one’s career progression. It starts from a prehire to a young professional, moving through the mid-career stage and the highly experienced subject matter expert, and finally reaching a post-employment stage. This element is a measure of gain in professional work experience with the passing time. It also reflects the shifts of one’s larger and broader goals relating to the social contexts including family, work, and personal interests. These goals and their foundational intentions are directly affected by the competency level of soft skills.

Socio-economic, cultural, and traditional. The third element is highly dominated by the geographical location of the workplace. This element identifies the desired soft skills attributes for individuals based on place of work, exposure to local and regional cultures, and socio-economic situations. The key element is the recognition of the cultural beliefs and socio-economic conditions that affect the patterns of communication and interaction. The cultural beliefs tend to be invisible and fundamentally affect the frame and content of acceptable social skills.

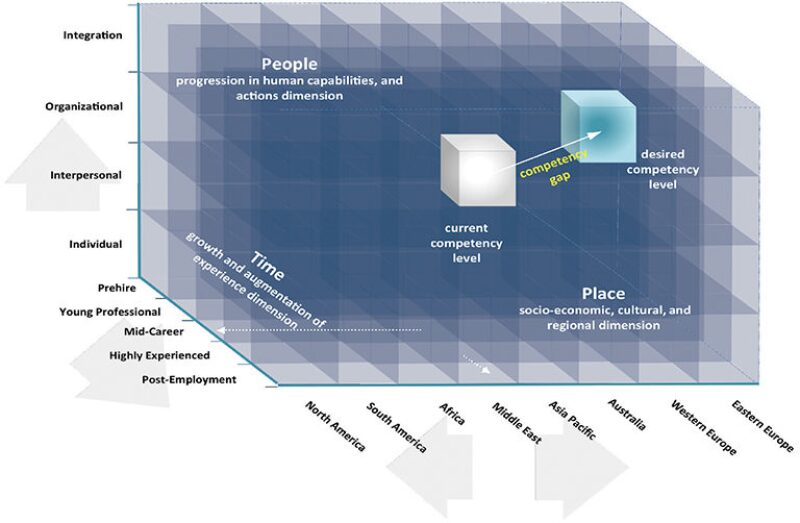

While the first two elements are governed by a continuing journey through time and personal maturity dimensions, the changes in the third element can be abrupt depending on the attributes needed for the new work assignment. It is then helpful to construct a three-dimensional (3D) soft skills matrix that combines the three soft competency elements (Fig. 7) into a tool that allows measuring one’s competency level and identifying the gaps (current vs. expected). Each individual occupies a cell (cube) within this 3D space of people-time-place matrix that defines his or her growth, maturity levels, and current place of work. There also exists a target cell that defines the required or expected attributes for the same individual in the next role, job location, or maturity. Then, the gap in interpersonal skills is the distance between the two cells as shown in Fig. 7. Once the gap is identified, then adequate training can be prescribed to remedy the deficiencies in a pro-active manner.

The SPE Soft Skills Council recognizes that the methodology described in Fig. 7 will have to be refined for different regions in the world based on the regional cultures, traditions, and way of life. This will be accomplished with the recruitment of additional SPE members who possess the cultural background and the knowledge of working and living in various regions of the world.

Conclusion

In the emerging and unpredictable workplace, it is insufficient to have technical knowledge and ideas; one must be able to articulate and convey them to others so that they can be improved and, most importantly, implemented to impact our business results. It is important to manage professional relationships well in the complicated environment of our global workplace. As providers of energy in the international marketplace, we want to work in a manner that is congruent with and in support of the recognized principles and values of our social constructs. That is why we must couple technological know-how with globally recognized effective human interactions to ensure success for both petrotechnical professionals and our industry.

The model of people, time, and place concept is a starting point for engagement so that we can better manage and prepare for the ongoing changes and saving of time to autonomy for our industry professionals. This effort will require more human interactions, particularly in transferring tacit knowledge from the subject matter experts to the new entrants into our profession.

References

- Fattahi, B. et al. 2012. Soft Skills Council: A New SPE Initiative. J. Pet Tech 64 (8): 80–82.

- Are They Really Ready to Work? 2006. Report published by The Conference Board, Partnership for 21st Century Skills, Corporate Voices for Working Families and Society for Human Resources Management.

- Heath, C.P.M. 2000a. The Technical and Non-Technical Skills Needed by Canadian-based Mining Companies. Journal of Geoscience Education 48 (1): 5–18.

- Heath, C.P.M. 2000b. Technical and Non-Technical Skills Needed by Oil Companies. Journal of Geoscience Education 48 (11): 605–617.

- Heath, C.P.M. 2002. Technical, Non-Technical and Other Skills Needed by Canadian Mining, Petroleum and Public Sector Organizations. Geoscience Canada 29 (1): 21–34.

- Heath, C.P.M. 2003. Geological, Geophysical, and Other Technical and Soft Skills Needed by Geoscientists Employed in the North American Petroleum Industry, AAPG Bulletin, 87 (9): 1395–1410.

- Nisen, M. 2013. Now You Might Have to Show Emotional IQ to Get Into Business School. Business Insider. May 2.