Front-month Nymex West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil futures settled at a record low -$37.63/bbl on 20 April. The settlement was not driven lower only by weak demand and ample supply brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. It was driven by a lack of storage capacity.

As WTI moved to negative territory for the first time ever, it meant trade participants were paying buyers to take oil volumes as storage in Cushing, Oklahoma, the delivery point for WTI, was unavailable. It also highlighted the severity of the lack of US oil storage.

However, the crude storage issue is not limited to the US. It has become a global issue during the pandemic. As Nymex WTI dove negative, its European Brent oil counterpart fell as low as $15.98/bbl during the same week, its lowest level since June 1999.

Global and domestic production cuts are in the works, but until then, many countries, companies, and market participants are looking at typical oil transportation and storage methods, and scrambling to find storage solutions and alternatives.

Cushing vs. the World

Leading up to the record-low WTI contract, inventory data from the Energy Information Administration (EIA) showed US crude inventory at 518.6 million bbl for the week ending 17 April. This was up by 15 million bbl (3%) from a week earlier and up by 58 million bbl (13%) from 460.6 million bbl at the same time last year.

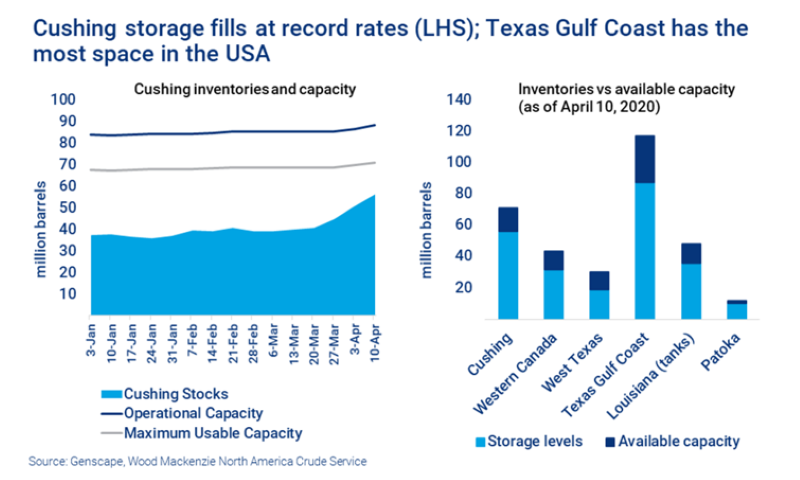

At Cushing, EIA data showed oil stocks were at 59.7 million bbl for the week ending 17 April. This was up by 4.8 million (9%) from 49 million bbl a week earlier and up 10.5 million (24%) from 44.4 million bbl at the same time a year earlier.

Although inventory at Cushing was up for seven consecutive weeks leading up to the WTI contract, it was still well below the highest level recorded at 69.4 million bbl during the week ending 7 April 2017.

Analysts and industry groups are quick to point out, though, that storage at Cushing has already reached capacity and may already be spoken for. Inventory moved up another 3.6 million bbl at Cushing in the subsequent week ending 24 April.

“We think storage at Cushing will reach effective “tank tops”—meaning it has no more usable spare capacity—in May,” said Wood Mackenzie Vice-Chair Ed Crooks.

“Cushing, Oklahoma, is a microcosm of the wider picture,” said Simon Flowers, Wood Mackenzie’s chairman and chief analyst. “Oil prices in Texas have incentivized producers to send crude to the Cushing hub; weak demand from refineries in the Midwest and Gulf Coast have kept it there.”

Flowers added that US storage tanks are filling up rapidly, citing the three largest weekly builds on record were in consecutive weeks from late March, based on Genscape’s proprietary twice-weekly tank monitoring.

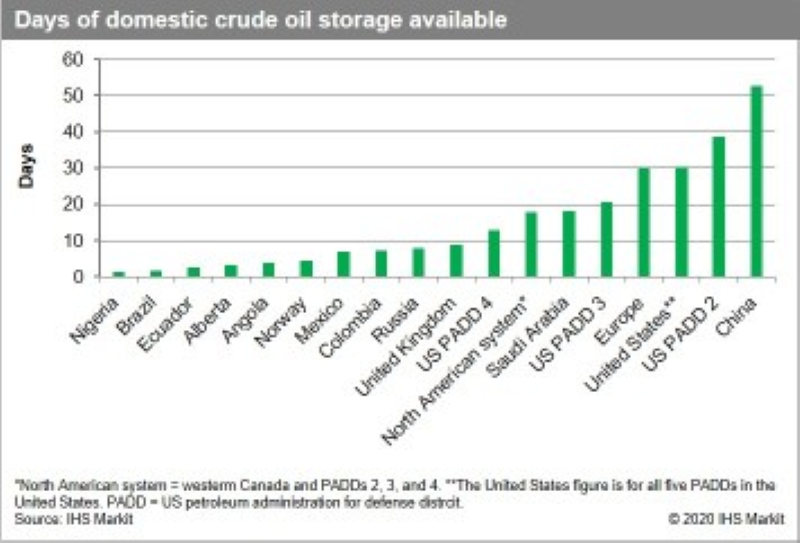

Even before Nymex crude went negative, analysts were expecting a strain on storage capacity abroad as well. IHS Markit said in late March that global output levels could not be sustained throughout Q2 because oil storage capacity would fill up.

IHS Markit estimated that the gap between world oil (liquids) supply and demand will be 7.4 million B/D for Q1 2020 and 12.4 million B/D in Q2.

This differential adds up to a first half 2020 surplus of 1.8 billion bbl, which exceeds the upper end of IHS Markit’s estimate of available (empty) crude oil storage capacity of 1.6 billion bbl.

Among the largest oil producers, IHS Markit’s analysis shows Russia has the least amount of available storage capacity (8 days), followed by Saudi Arabia (18 days), and the US (30 days). The largest producer, China, may have as much as 52 days of daily production storage available.

Major oil storage firms are either at or nearing their capacity limits.

Vopak, the largest independent oil storage company in the world, told various media outlets in April that available oil capacity is almost completely sold out.

As companies run out of storage space, more buildouts are on the way.

Liquids terminal and logistics provider Moda Midstream placed into service the final 495,000-bbl tank from its 10 million-bbl crude oil expansions at the Moda Ingleside (Texas) Energy Center (MIEC) in and the Moda Taft (Texas) Terminal on 28 April. The completion of the storage expansion brings total storage capacity at MIEC and Moda to approximately 12 million bbl.

Construction also started at MIEC on a new expansion phase for an additional 3.5 million bbl of crude oil storage. The company said it has obtained permits to construct additional crude oil storage capacity at both MIEC and Moda and is discussing further expansions with customers.

Outside of the US, more storage is also being planned. McDermott International’s CBI Storage Solutions was awarded three contracts in late April for the engineering, procurement, fabrication, and construction (EPFC) of 38 tanks and 13 spheres in multiple locations across Saudi Arabia. The company said projects of this type typically take 1–2 years to complete from the time contracts are signed.

With the hunt for available tank space ongoing, the market may also look to various strategic petroleum reserves (SPRs) as a storage option.

Strategic Reserve Storage Space for Lease

The US said in early April it was looking to lease out space for companies to store oil in the SPR after its plans to buy millions of crude oil barrels fell through.

The Department of Energy (DOE) later suspended its plans to buy 77 million bbl of US crude, after the requested $3 billion in funding for the project was not included in a $2-trillion stimulus package that was approved by the US Congress.

At the time of this writing, EIA data showed SPR inventory at 636.1 million bbl for the week ending 24 April. This was up by 1.2 million (0.2%) from 635 million bbl a week earlier. It was also the first increase seen in the SPR since early December 2019.

The increase comes after the US entered into negotiations with nine companies on an agreement to rent space in the US SPR to store 23 million bbl of crude. Although the list was not made available to the public, Reuters said the nine companies were as follows: Chevron, ExxonMobil, Alon USA, Atlantic Trading, Energy Transfer, Equinor, Mercuria Energy America, MVP Holdings, and Vitol.

Even with the increase, capacity was still 90 million bbl below the highest capacity held by the SPR, 727 million bbl in December 2009.

When Nymex WTI went negative on 20 April, however, President Trump reiterated the plan and said the US would look at putting as much as 75 million bbl into the reserves.

One country has also locked in its position with the US SPR.

Australia said on 21 April it would spend $59 million to build an emergency oil stockpile that will be stored in the US SPR. The deal is for an initial period of 10 years and comes as the country says its own domestic storage tanks are full.

The deal is also part of Australia’s effort to meet its International Energy Agency (IEA) requirements. In accordance with the agreement on an International Energy Programme, each IEA country has an obligation to hold emergency oil stocks equivalent to at least 90 days of net oil imports. In case of a severe oil supply disruption, IEA members may decide to release these stocks to the market as part of a collective action.

India, another major oil consumer, said its SPR will be full by the third week of May. The country’s total combined capacity is 5.33 million metric tonnes, spread out in three locations in southern India—Visakhapatnam, Mangalore, and Padur. As of mid-April, India said this was just over half full.

An S&P Global Platts Analytics Insight said while India fills its SPR, the lack of space also means an opportunity lost. Platts added that India’s reluctance stems from the high costs involved, not only in building out the tanks and necessary infrastructure, but also in maintaining and holding the oil.

With tank space limited inland, it left the market looking to offshore alternatives, which are also filling up quickly.

Storage on the Water in High Demand

Key ports around the world are becoming packed with ships, being used for floating storage until there is enough space in onshore storage tanks to allow for the discharge of their petroleum cargo.

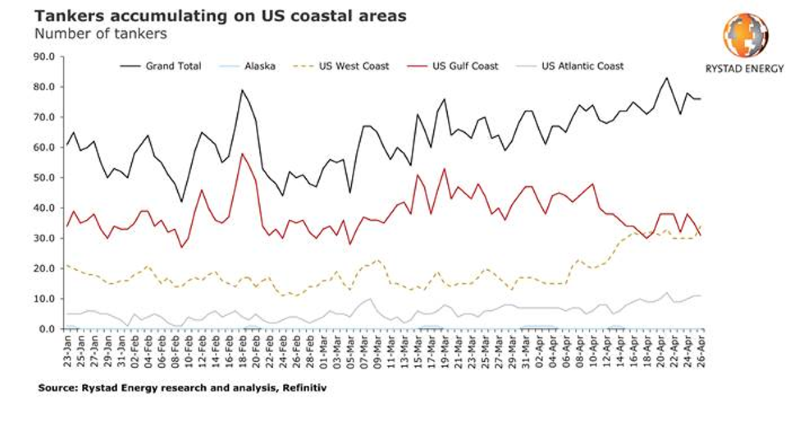

The US Coast Guard said on 24 April it was monitoring 27 tankers off the coast of Southern California, which analyst groups estimate are holding about 20 million bbl of crude.

A similar situation has developed in Singapore, where about 60 clean-fuel tankers are at a standstill.

More ships are expected to arrive in the US. A Rystad Energy analysis showed 28 tankers with Saudi oil, including 14 very large crude carriers, will arrive on the US Gulf and West coasts between 24 April and 24 May carrying a total of 43 million bbl of crude oil.

Rystad said the fleet, with oil loaded at Ras Tanura, will join an existing congestion of 76 tankers that are currently waiting to unload in US ports. Most of these tankers are on the West Coast, where 34 are waiting in line to offload about 25 million bbl of crude.

Rystad added about 31 tankers, carrying a similar load, are waiting for a slot to unload on the US Gulf Coast, though this number of tankers is not unusual for the Gulf.

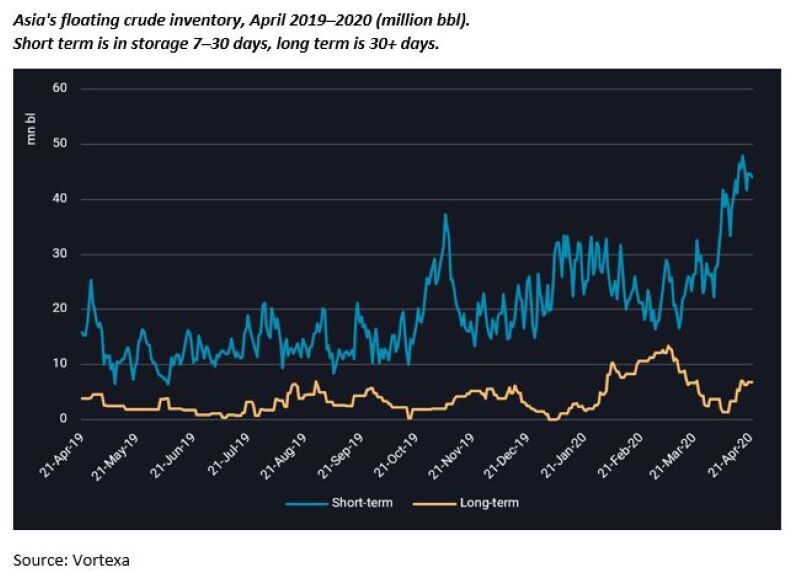

Outside the US, key regions such as Asia, which currently accounts for around 45% of total global floating storage, has seen a swift build in offshore stocks in recent weeks, notably off India and Southeast Asia.

Market intelligence group Vortexa said the growing clusters of floating storage outside refining centers in Asia reflect onshore storage capacity nearing limits, prompting refiners and other players to move incremental barrels onto offshore tankers and float them near consumers to shorten delivery time. Vortexa added the rise in recent tanker bookings for floating storage—many of which have yet to commence their storage period—should see additional strong builds in Asia in coming weeks.

On a global basis, Vortexa said the rise in floating storage in Asia has helped to lift overall crude in floating storage to above 120 million bbl in mid-April, surpassing the highs of 2016.

The group added that the flotilla of floating storage bookings that will come on line in subsequent weeks is expected to lift volumes higher, and of these, many are expected to exercise their storage options in Asia.

“If global crude surplus continues rising, storing crude on tankers, even at a loss for operational purposes, could become more entrenched,” the company said.

Susan Grissom, chief industry analyst for the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers, noted that while crude can be stored all along the petroleum supply chain—from wellhead to pipelines, bulk terminals, tankers, and refineries—challenges are emerging, especially with the increased use of tankers for storage.

When marine vessels are used for storage—a status given once a ship is stationary for a minimum of seven days—fewer vessels are available to ship petroleum. The effects reverberate and can lead to increased costs for crude oil and refined product shipping and delayed voyages, Grissom said.

“Refineries plan crude supplies well in advance, often 8 to 12 weeks before the crude oil will be needed at a facility,” Grissom explained. “When there is a sudden and dramatic drop in demand, as has been the case because of COVID-19, refineries take steps to reduce crude receipts.”

Crude supplied from onshore storage terminals may be able to remain stored at the terminal. But when crude oil is supplied from a marine vessel, the options are more limited. “Using the marine vessel to store the crude is often the most reasonable option,” Grissom added.

Shipping journal Lloyd’s List Maritime Intelligence said this week that floating storage of refined products such as gasoline and jet fuel is forecast to hit fresh highs over the next 6 weeks, adding that tank capacity is not expected to recede until the end of June.

Lloyd’s List added between 30 and 114 Aframax-sized tankers will be needed to accommodate the accelerating floating storage demand. Its estimates of current clean floating storage levels range from 40 million to 65 million bbl, substantially less than crude oil volumes. The group said about 163 million bbl of crude and condensate have been measured on 114 tankers over the past 20 days or more.

In addition to using marine vessels for storage, the market is also looking at ways to utilize pipelines and rail cars to store oil. Other options include converting storage used for other products, such as natural gas liquids.

Pipelines and Rail Cars Also in High Demand

In the US, midstream service provider Energy Transfer told price reporting agency Argus Media that it was looking for ways to idle two pipelines in Texas by moving product around and using them as storage space by mid-May. The lines would provide about 2 million bbl of storage space.

Argus added that the pipeline company was in the process of asking the Texas Railroad Commission for permission to change the method of operation on the lines.

Another major pipeline operator, Enterprise Products Partners, said it was opening the northbound capacity of its Seaway pipeline, which runs from Cushing to Freeport, Texas, and through Texas City, Texas.

For rail cars, Cowen and Company Freight Transportation analyst Matt Elkott said in recent media interviews that rail cars could be used to store crude, but this was unlikely for now. Elkott told one railroad industry publication that Cowen and Company estimated at least 30,000 class-3 flammable liquid tank cars in North America, each with capacity of more than 30,000 gallons, that could be deployed to hold oil.

US crude oil by rail volumes have fluctuated in recent years, and traffic has been on the decline due in part to oil prices and pipeline capacity. Data from the Association of American Railroads (AAR) showed in 2014, US class-I railroads peaked at 493,146 carloads in 2014, but then fell to 128,967 carloads by 2017 before rising in 2018 and 2019.

In an AAR rail traffic data report on 1 April, Senior Vice President John T. Gray said the collapse in oil prices was hurting rail shipments of petroleum products. US rail traffic from AAR showed petroleum and petroleum products for the week ending 25 April was at 9,519, which is down 30.4% compared with the same time a year earlier.

Rail cars are not the only option appearing to be an unlikely destination for crude storage in the short term.

Petrochem Storage and Trucks: Viable Solutions?

As the overhang of crude oil increased significantly over the past month, inquires for available transport trailers for storing crude have intensified. But if market players are looking at truck trailers as a means of storage, they may be out of luck, since their capacity is very limited.

Truck transport trailers can typically carry around 200 bbl of oil, compared with 50,000–70,000 bbl in a unit train, or hundreds of thousands of barrels in large independent terminal tanks, which unfortunately are near capacity in many areas.

“We are probably the court of last resort,” said Steve Boyd, a senior managing director for US-based wholesale petroleum marketer Sun Coast Resources.

Headquartered in Houston, with a total of 18 offices throughout Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma, Sun Coast is a large wholesale petroleum marketer with over 800 transport and bobtail trucks in its modern fleet, supplying a complete line of petroleum products to thousands of customers. Although the company’s primary business is supplying gasoline and diesel fuel, similar companies have been getting many more inquiries about storing crude and other petroleum products.

“When producers and traders start calling fuel marketers for storing crude oil, you know they are pretty desperate,” Boyd said. “They’ve gone to major terminal operators like Kinder Morgan and Vopak without success, so yeah, they are calling us in hopes we have some storage available for lease. We just don’t have the large storage capacity they are seeking.”

Another less-viable option appears to be looking elsewhere downstream to the petrochemical industry for storage options.

Petrochemicals are not impacted equally by COVID-19 and have not experienced the same storage infrastructure challenges as crude oil,” said Rob Benedict, senior director of petrochemicals, transportation, and infrastructure for AFPM.

Petrochemical feedstocks including ethylene, propylene, benzene, and xylene can be produced by chemical facilities and also through petroleum refining. The plastics and polymers manufactured from petrochemicals are the building blocks for modern industries, ranging from electronics to cosmetics, packaging, and medicine.

Benedict notes that while petrochemicals are derived from crude oil, their transportation containment and storage requires specific types of materials, fittings, and walls, which may not necessarily be compatible with refined products or crude.

“You can’t simply swap out crude oil with petrochemicals when you are talking about storage tanks or rail cars. There are specific design standards for each and not a whole lot of interchangeability,” Benedict said.