The generation gap in the upstream oil and gas sector has grown even wider due to economic downturns, technology, and the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in four very different generations having to work together: the Baby Boomers, Baby Busters, Millennials, and Zoomers. This article examines the strengths and weaknesses of each generation and shares effective methods used by the technology sector to help the generations get along well at work so we can have effective teams in the energy industry.

Introduction

From a historical perspective, the term “generation gap” originated from the cultural disturbances of the 1960s, when parents who served in World War II reacted strongly to their children participating in antiwar demonstrations during the Vietnam War era (Wortman 2016). More recently, Mendez (2008) defined the generation gap as a difference in values and attitudes and a lack of understanding between older and younger persons due to their different experiences, opinions, habits, and behaviors.

Patil (2014) describes these differences between generations from a sociological perspective, where the gap is due to rapid modernization and expansion of education via the Internet, which causes many older persons to suffer from a “cultural lag” in knowledge of various aspects of today’s lifestyle. This phenomenon coupled with older ones not being able to carry out the traditional function of guidance and knowledge transfer to younger ones can lead to heated discussions between these generations on political and social issues (Patil 2014).

Four Workforce Generations

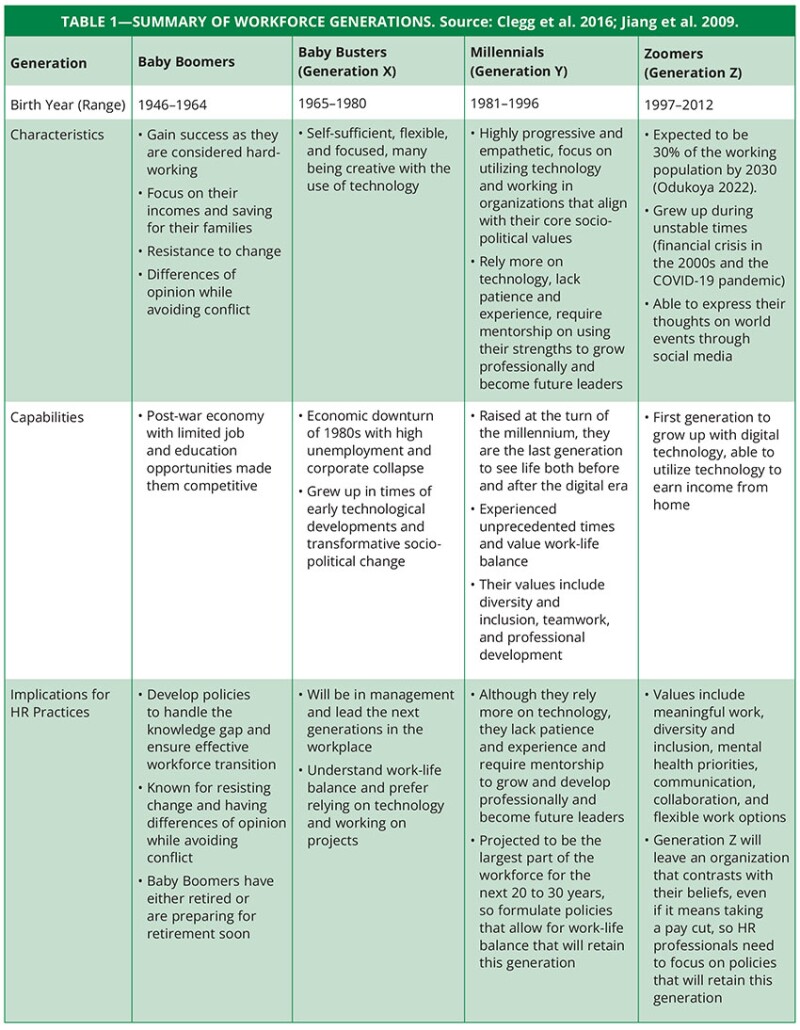

To understand the views of the older and younger age groups, one must examine the characteristics, capabilities, and working opportunities of the four generations that are currently in the workplace. These are summarized in Table 1.

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (2023), the labor force population has an age range of 16 to 75. Based on the 2020 SPE Salary Survey, the energy industry’s age population ranges from ages 24 to 64. These two surveys show there are four generations working together in all sectors, so it is expected that organizations will be faced with challenges such as workplace conflicts, misunderstandings, and ineffective change management.

Energy companies in particular are also confronted with knowledge gaps that have widened over the past four decades due to two crude oil price gluts that caused long-term effects.

Two Oil Gluts

The first is the well-known oil glut of the 1980s, when crude oil prices declined below $20/bbl due to the low demand after the 1970s energy crisis (Boopsingh & McGuire 2014). The high supply and low demand led to a drastic decline in petroleum production, and the resulting downturn in the energy industry led to many companies having massive layoffs. During this time, many Baby Boomers and Baby Busters shifted their jobs to other industry sectors, with Baby Busters preferring the information technology sector, which was more viable (losses of 5-15%) than the energy and finance sectors (30% losses) (Jiang et al. 2009). Further evidence of Baby Busters moving away from the oil and gas industry was the drop in petroleum engineering graduates from universities in the late 1980s (Walrond 2014).

The second oil glut occurred in April 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, when Brent crude oil fell to USD 9.12/bbl and the global demand for crude oil fell by 16.4 million BOPD (EIA 2021; IEA 2020). As in the 1980s, organizations were forced to adjust their business plans to adapt and survive. The difference with this oil glut was that those companies that were able to be resilient shifted their focus and resources towards the energy transition.

The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) reported in mid-2020 that several companies announced shutting in and curtailing producing wells to reduce the oversupply of crude oil. Royal Dutch Shell cut their dividend for the first time since World War II to strengthen their resilience during the pandemic (BBC 2020). Even using these methods to adapt, the US saw 107,000 oil and gas industry jobs lost by the end of 2020 (Egan 2020). This brought about another instance when workers fled to other sectors such as information technology (Egan 2020).

As a result of these two oil gluts, our industry faced many early retirements, and workers moved to different sectors. Companies faced ageism challenges, as cost-costing measures retrenched many of their older workers. This method was prominent especially during the pandemic (Hennelly & Schurman 2023). In addition, Millennials and Zoomers (Generation Z) aimed for better work-life balance than our industry offered, and their concerns about the environment and sustainability led them to quit the oil and gas sector (Charlton 2023).

Organizations realized that they needed to build a reliable and efficient workforce not just for today, but for the future (Hennelly & Schurman 2023). To do this, upstream organizations need to understand these generations better and support the things that matter to them (Charlton 2023).

There are several methods that have been employed in other sectors to address the age gap issue, and some of these can be applied to our sector. We present three specific approaches to address the widening age gap in the energy sector.

1. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Strategies

Company executives are advised to integrate age diversity into their diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) strategies to increase operational effectiveness and competitiveness (Hennelly & Schurman 2023). Embracing a multigenerational workforce improves collaboration between older and younger employees, leading to increased diversity. Case studies show an improvement of up to 30% in team performance with the acceptance of a multigeneration workforce (Hennelly & Schurman 2023). Many energy organizations have implemented strategies such as flexible work options, hybrid schedules, phased retirement, and job-sharing to retain an age-diverse workforce.

It is also the role of executive management to foster a psychologically safe work environment, which promotes high performance, reduces turnover, and boosts revenues (Hennelly & Schurman, 2023). Once an organization views generational differences as opportunities for collective learning and respectful debate, managers can mitigate the tendency for different age groups to dismiss each other’s ideas, resulting in increased trust. Sectors like finance, technology, and healthcare benefit from diverse and inclusive leadership while emphasizing equality, openness, and a sense of belonging among employees (Dixon‑Fyle et al. 2020). This approach, which supports the development of inclusive practices and helps bridge generational gaps within organizations, should be considered by companies in the energy sector.

2. Reverse Mentorship

The second approach that should be taken to reduce the generation gap in the energy sector is reverse mentorship. This is a partnership between a senior level employee and a junior employee in which the knowledge, expertise, and skills are shared from the junior employee to the senior (Carruthers 2021). This mentorship program was very popular in the 1990s, when its objective was for the younger generation to inform older executives and management on technological changes. Today, reverse mentorship is a method to connect varying generations of workers who have something in common, e.g., those with similar ethnic backgrounds (Reeves 2023). Such a mentorship program can occur within a company’s existing mentorship program (Quast & Hedges 2011). Case studies of reverse mentorship show communication improvement when the different generations can meet to cultivate their communication skills and understand new perspectives. Gerry Tamburro, former managing director at BNY Mellon’s Pershing, reported success in their reverse mentorship program, as executive management reached out to Millennials to get their input in organizational decisions, resulting in a 96% retention rate with Millennials (Jordan & Sorell 2019).

In the energy sector, reverse mentorship can empower emerging and established leaders and bring the generations closer. Reverse mentoring not only reduces the gap, but also assists with bolstering the retention of the younger generations, who may be more inclined to stay at the company because they feel more valued and enriched (Indeed 2024).

3. Employee Resource Groups

Employee resource groups (ERGs) are voluntary, employee-led groups formed around shared characteristics that aim to foster DEI within an organization (Taylor & Moffat 2023). ERGs are used by organizations to drive mentorship programs and help foster connections among employees with similar backgrounds and interests (N. Catalino et al. 2022). Research shows that companies in the technology sector have an average of 10 different ERGs that their employees can join, including culture/ethnicity, people with disabilities, working parents, and age minorities (Carruthers 2022). Though overall ERG participation may be small (e.g., 8% in multinational companies worldwide), they have significant impact by supporting DEI initiatives, enhancing employee orientation, and driving innovation, which can improve productivity (Carruthers 2022). For example, Ernst & Young (EY) has nine ERGs that engage 30,000 employees. With these groups they were able to increase diversity representation in their promotions worldwide (Wilson 2023).

Establishing ERGs in the energy sector could assist with bridging the generation gap by fostering connections among employees with their similar ethnic backgrounds and interests. ERGs provide a platform for employees to voice their experiences, support one another, and understand different age perspectives. This would be useful for succession planning and leadership development to provide smooth transition from Baby Boomer managers to Generations X, Y, and then Z. This approach can enhance inclusion and retention, especially among the younger employees. To maximize the effectiveness of ERGs and bridge generational divides, it is clear communication within and between ERGs and executive management is essential to ensure alignment with organizational goals and address issues effectively (Catalino et al. 2022). Regular updates and strong leadership support are crucial for ERGs to thrive and meet their objectives.

Conclusion

This article reviewed the four generations in the upstream energy workforce, focusing on their ages, their personality traits, and their unique characteristics. The historical events over the past 40 years in the oil and gas industry may have widened gaps, but three strategies—DEI, reverse mentoring, and ERGs—have proven effective in enhancing collaboration across generations in other sectors, and these can similarly foster understanding and improve productivity within the upstream oil and gas industry.

For Further Reading

Shell Cuts Dividend for First Time Since WW2, BBC (2020).

From Oil to Gas and Beyond: A Review of the Trinidad and Tobago Model and Analysis of Future Challenges by T. Boopsingh and G. McGuire (2014).

This Is What’s Worrying Gen Z and Millennials in 2023 by E. Charlton, World Economic Forum (2023).

Managing and Organizations: An Introduction to Theory and Practice by M. Clegg, M. Kornberger, T. Pitsis (4th Edition, 2016).

Diversity Wins: How Inclusion Matters by S. Dixon-Fyle, K. Dolan, D. Hunt et al., McKinsey & Company (2020).

Diversity Still Matters by K. Dolan, D. Hunt, S. Prince et al., McKinsey & Company (2020).

The Pandemic Made 107,000 Oil and Gas Jobs Disappear. Most Aren’t Coming Back Anytime Soon by M. Egan, CNN Business (2020).

Crude Oil Prices Briefly Traded Below $0 in Spring 2020 But Have Since Been Mostly Flat, US Energy Information Administration (2021).

How The Oil Glut Is Changing Business by R. Hershey Jr., The New York Times (1981).

The New Generation Gap by N. Howe and W. Strauss, The Atlantic (1992).

Oil Market Report—July 2020, International Energy Agency (2020).

Mapping Decline and Recovery Across Sectors by B. Jang, T. Koller, Z. Williams, McKinsey & Company (2009).

Generation Gap by N. Mendez, Encyclopedia of Aging and Public Health (2008).

The Best Mentorships Help Both People Grow by D. Nour, Harvard Business Review (2022).

The Changing Generational Values, Johns Hopkins University (2022).

A Sociological Perspective of Generation Gap by S.K. Patil, The International Journal of Innovative Research and Development (2014).

Civilian Labor Force, by Age, Sex, Race, and Ethnicity, US Bureau of Labor Statistics (2024).

Bridging Generational Divides in Your Workplace by D.S. Hennelly and B. Schurman, Harvard Business Review (2023).

Guide to Employee Resource Groups: The Critical Ins and Outs by R. Carruthers, Together(2022).

Reverse Mentoring: A Toolkit for Diversity and Inclusion Initiatives by R. Carruthers, Together (2021).

What Are Employee Resource Groups (ERGs)? by N. Taylor, UKG (2023).

Reverse Mentoring: What It Is and Why It Is Beneficial by L. Quast, Forbes (2011).

Reverse Mentoring: What It Is and How To Set Up a Program, Indeed (2024).

Why Reverse Mentoring Works and How To Do It Right by J. Jordan and M. Sorrell, Harvard Business Review (2019).

Effective Employee Resource Groups Are Key to Inclusion at Work. Here’s How To Get Them Right by N. Catalino, N. Gardner, D. Goldstein et al., McKinsey & Company (2022).

Remember the 1980s Oil Glut: Last Time We Saw Conditions Like This Prices Stayed Low for 17 Years, Warns BP’s Lord Browne by Reuters, Financial Post (2020).

Shell To Cut up to 9,000 Jobs as Oil Demand Slumps, BBC (2020).

Understanding Generation Gap, YouTube (2020).

Maryse Jackman is employed in the Resource Management Division at the Trinidad and Tobago Ministry of Energy and Energy Industries. Her work functions include geological evaluations of open/idle blocks for the purpose of competitive bid rounds. An SPE volunteer since 2017, she has held various positions in the Trinidad and Tobago Section such as director of publicity and editor of the section’s newsletter, Top Drive. She is currently serving as chairperson of the section. Jackman holds a BSc in geology from the University of the West Indies and an MBA with specialization in oil and gas management from the University of Bedfordshire.

Jeanne Perdue worked as a chemist at the Texaco research labs, then became senior technology editor for Hart Energy’s E&P magazine and later launched the award-winning Upstream Technology magazine. She spent 14 years as technical writer at Oxy before she retired. She is an SPE Distinguished Member and serves on the University of Houston Petroleum Engineering Advisory Board and HCC Petroleum Technology Advisory Board. Perdue holds a BS in chemistry from the State University of New York at Albany.