There is no formula for properly spacing wells in unconventional plays. When a reservoir consultant recently described conversations with clients about how many wells they could drill per acre, it sounded like a doctor advising a patient considering back surgery.

“I am not trying to tell you what your spacing should be,” said Miles Palke, management senior vice president for Ryder Scott, adding that the modeling and production history matching his company offers is “a process to help you inform your decision.”

The cautious approach was understandable in his talk at the recent SPE Hydrocarbon Economics and Evaluation Symposium. Well-spacing decisions are increasingly tricky because of the potential downsides, from damaging hits to older parent wells to production from new child wells falling short of the old wells.

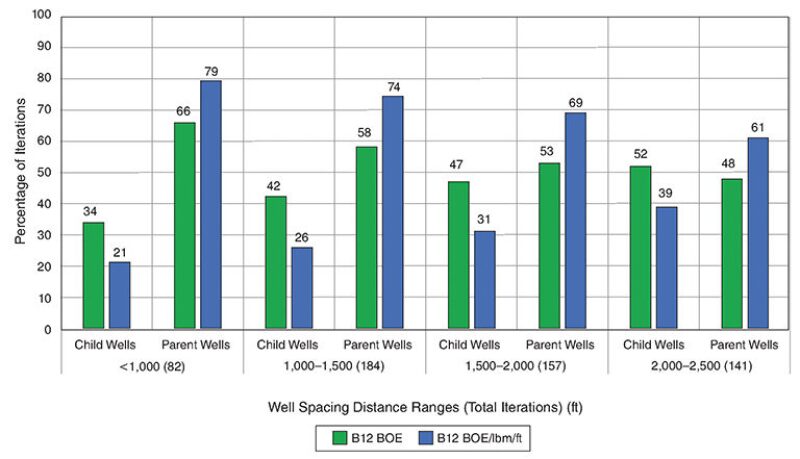

A recent technical paper authored by Schlumberger (SPE 191799), based on data from the Wolfcamp shale play in the Permian’s Delaware Basin, found that when a new well is drilled within 1,000 ft of an older well, the older parent well outperformed the child well 66% of the time. When the results were adjusted for the bigger, more expensive completions now common, 79% of the older wells performed better.

It is getting harder to avoid the issue of well spacing. In its recent earnings call with investment analysts, Schlumberger said that 70% of the wells drilled in the Eagle Ford are infill wells, as are 50% of those wells drilled in the Permian.

While there is a lot of agonizing about fracs hits when wells are closely spaced, wider spacing also has its risks. Schlumberger predicted that even when the wells are 2,000–2,500 ft apart, the parent wells perform better 61% of the time, when the production was adjusted for the larger volumes of proppant per foot now commonly used. As wells get farther apart, there is a growing chance that productive rock in between will never be stimulated.

Well interactions are a constant reminder that fracturing does not create networks of producing fractures shaped like shoe boxes that can be lined up neatly on a shelf. Fracturing the maximum volume of a reservoir requires dealing with the contact that comes when wells with irregularly shaped fracture networks are located side by side.

“People talk about well interference and bring it up as if it is a bad thing,” said Erdal Ozkan, SPE’s reservoir technical director. The petroleum engineering professor at Colorado School of Mines added that overlapping production “has always existed between two wells in the same field. There will be interference. If you reduce the drainable area, you reduce productivity of each well.”

Judgment Calls

Operators turn to consultants such as Ryder Scott for history-matched reservoir models because they want results that line up with the output from actual wells. But that leaves a lot of room for judgment calls.

Using the same wells for an equivalent history match, you can arrive at a range of options from 80 acres to 120 acres per well, Palke said. “If you have a big land position, that (difference) is a lot of wells. You would want to do a lot of work to decide which of those is the best decision,” he said.

Compared with conventional reservoirs, predicting the production from these sprawling, thick, ultratight layers of source rock is more difficult. For one, data are limited. While reservoir modelers want more data from conventional fields, “now we have less,” Palke said.

And there are more factors to consider. Production from unconventional rocks is a function of both the complex geology around the wellbore and how it was hydraulically fractured, among many factors that will affect total production.

The number of items listed on slides during the conference presentations that day was mindboggling, which is why exploration and production companies are turning to machine-learning programs.

“We are more into machine learning, and based on this conference, other companies are,” said Michael Verney, an executive vice president for McDaniel & Associates Consultants, a reservoir consulting firm.

Two-dimensional charts showing correlations between a couple of variables fail to capture the complexity of unconventional development. Computers are good at the computation-intensive process of identifying correlations with three variables, which are displayed in cubes, and it gets more complicated from there.

“What it allows us to do is create a cube of relations. Now we are building cubes of cubes.” said Jared Wynveen, an executive vice president at McDaniel. That is a visual representation of their goal, which is to get to “the third-, fourth-, and fifth-level variables.”

Parental Conflicts

Wells are spaced too closely when they reach the point where they “interfere too much” with each other, Palke said.

For years, the unconventional business delivered steadily improving production results with optimized completions. Now those doing infill development are dealing with locations where the “parent was optimized but the child well suffered,” said Dylan Loughheed, Canadian business development manager for NCS Multistage.

Schlumberger’s analysis of data from the Permian found that well age matters because an older well has reduced the pressure and hydrocarbon level more than a younger one. As the differential grows, so too does the growth of fractures from the child well into the depleted zone, where the potential is far lower than in the unstimulated rock and the risk of damaging interactions greater.

Wells fractured at the same time can be more closely spaced because the pressure levels should be roughly equal. While operators look for ways to fracture huge volumes of rock by simultaneously completing many wells at once, there is no avoiding older wells.

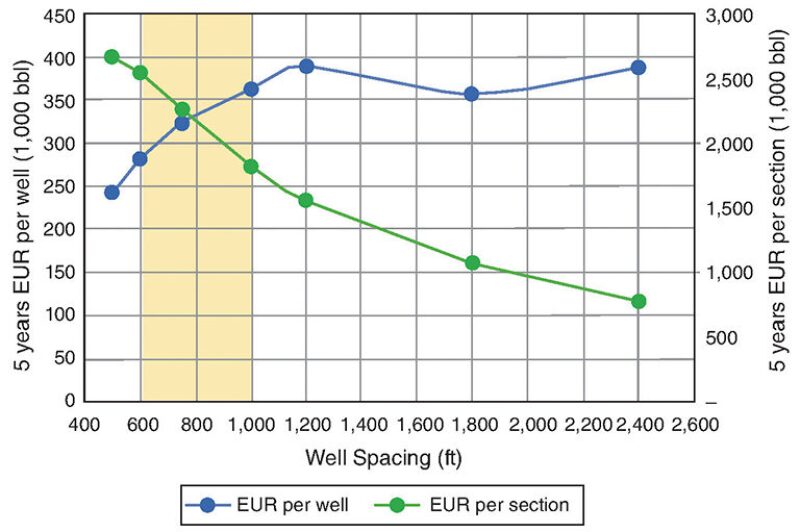

Schlumberger’s technical paper advised spacing new wells no closer than 900 ft from a well that had been producing 36 months or more—compared with a 750 ft minimum for one producing less than 12 months.

Making Tradeoffs

Schlumberger’s conclusions are the product of analysis using multiple models and data from the Delaware basin.

When it comes to well placement, the answer will vary with the location. The severity of interactions varies from basin to basin, and varies within them. They are a consideration in field designs, but there are many other factors that can significantly alter well placement, from lease lines to completion designs, and from available pipeline capacity to corporate budgets.

Newfield Exploration’s recently developed model includes a parent severity factor based on how the well has been fractured and how long it has been in production, said Sebastien Matringe, manager of reservoir optimization and analytics for Newfield. The index “should not be taken directly to be a risk factor. It is simply one of the hundreds of inputs that go into our model. The purpose of our model is exactly to decipher the respective influence of each input parameter on the production behavior.”

Newfield’s system was developed to allow decision makers to quickly work through a variety of development options and figure out which ones perform best. That begins with a data set describing the rock and fluid properties. Equally important in ultratight formations are details on how it is fractured and produced.

Newfield’s program includes well details, such as whether the toe of the well is higher or lower than the heel (toe-up or toe-down), whether the wellbore follows a winding path (tortuosity), and multiple completion design details from the amount of fluid and proppant pumped per foot to the number of stages and clusters.

Planners see how it all likely contributes to production potential on a gridded map, color-coded based on the production predictions. Stars on the map spot the wells, allowing users to compare predicted and actual results, Matringe said.

The machine-learning model delivered “some results that reinforce our expectations, and others that came as a surprise,” Matringe said.

Trust Issues

Surprises can offer valuable insights, but users need to realize that “machine learning can go all over the place,” said David Castiñeira, chief technology officer of Quantum Reservoir Impact, an oilfield analytics company.

Experienced experts need to “make sure everything is based on reality,” Wynveen said. Without that constraint on unworkable advice, there is the risk of “counterproductive outcomes.”

Some errors are visible, but easily missed. For example, economic projections comparing 1-mile-long and 2-mile-long laterals can be “drastically off” if the data are not adjusted to reflect the longer time it takes to flow back a 2-mile lateral before production begins, and the differing choke settings used, Matringe said.

Other possible errors can be lurking out of sight because the algorithm makes connections that are not visible. Some powerful algorithms, such as random forest or artificial neural networks, can identify complex relationships in the data. But the output does not provide decision makers information about the relationships used to do the evaluation, Matringe said.

“More advanced machine-learning models sometimes learn relatively convoluted relationships. This is why they are so powerful, but it makes them hard to fully understand. We therefore opted to use a simpler style of model—multivariate linear regression—which offers the advantage of being more transparent and can be interpreted easily,” he said.

“Building trust into the machine” is required to persuade engineers, geoscientists and decision makers to use this new tool, Matringe said.