While COP26 concluded with an apparently promising narrative in 2021, the conference failed to categorically agree on the need to “phase out” coal. And since last year, we have seen coal—the most emissions-intensive fossil fuel—be proactively sourced to provide security to the European energy grid as winter neared.

Such moves were a counterbalance measure meant to offset the supply squeeze of natural gas, which led to record-high gas prices.

So, on one hand, the emphasis for greener supplies of energy (via COP26) continues. On the other hand, the use of conventional sources of energy (such as coal) clearly remains a priority.

This presents what the author terms as “frictional energy” where rhetoric and reality diverge. As we witness this divergence take shape in the early part of this decade, keep in mind that it may continue into the next one as well.

Among other things, this is key to consider because frictional energy has geopolitical consequences. This has been illustrated by the EU’s decision in December 2020 to restrict investments for gas projects in favor of those directed toward renewable energy projects.

Around the same time, Nord Stream 2 was once more in play to provide gas from Russia to Germany (the largest EU member), albeit the flow of gas has yet to commence.

Notably, the EU is now looking at whether to allow some gas projects to be eligible for the “green” investment label. Such gas investments may circumvent the supply crunches that have recently “sent prices soaring in Europe…to the equivalent of around $180 per barrel of oil.”

The policy shift may also reduce Europe’s reliance on Russia (the largest gas importer to the EU) and its Nord Stream pipelines. As it stands, US liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports reached a new record high last December, with half of those shipments being routed to Europe to fill its supply gap.

To remind, the US—as part of its energy transition pledge—has recently rejoined the Paris Agreement (the antecedent to COP26).

Additionally, frictional energy accounts for the impacts on human life since having access to sufficient coal reserves may avoid a humanitarian crisis when a grid is shocked in the winter. This is a key reason as to why, last year, Europe began to aggressively source coal stocks. By protecting its grid, Europe was also protecting its populace.

The 2021 Polar Vortex which gravely impacted the US, exemplifies what can occur when a grid (in Europe or elsewhere) is left unprotected for millions of people because energy sources are not secured from a shock to the baseload supply. When the energy-rich Texas saw its power grid nearly collapse overnight, the cost was measured in fatalities and steep economic losses.

However, if we assume the new role of coal is to chiefly offset a gas shortage to protect grids, this erodes the Paris Agreement’s intent and increases the emissions that are supposed to be abated by for the sake of future generations by 2050—the key "net zero” year for many large corporations and nations.

Coal in 2022 is again challenging the energy transition, as we saw in Indonesia which is the world’s largest thermal coal exporter but has recently banned exports to avoid domestic power outages. This has triggered concerns for its biggest customers, including China and Japan, just as they head into the peak winter period for electricity demand.

The juxtaposition here is particularly notable in the case of Japan, which is a key signatory of the Paris Agreement but also one of the world’s top energy importers.

The Frictional Energy Dilemma

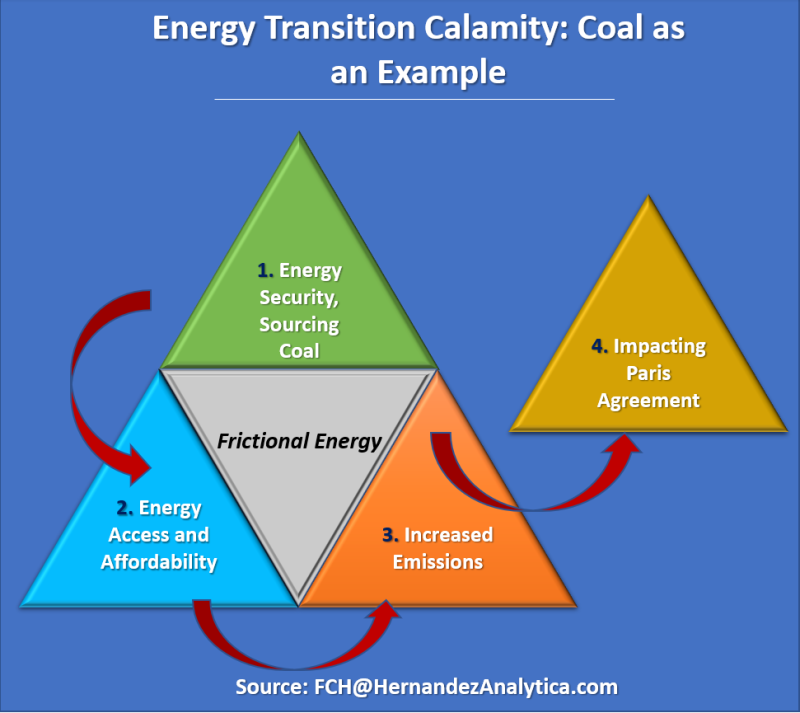

Frictional energy as a dilemma is visualized in the triangle diagram below.

It underlines the juncture where transition rhetoric and reality diverge. As an extension of Carl Von Clausewitz’s military doctrine, friction in this case is defined as “the only [concept distinguishing] real war from war on paper.”

The unfolding energy transition crisis, as some have considered it, comprises three interconnected components.

The first is defined by energy security, whereby countries must source coal to fill the supply gap. This effectively replaces a lower-emitting fossil fuel (e.g., natural gas) with a higher-emitting one.

By this logic, oil—the second highest emitting fossil fuel—can replace the use of gas, should coal, the highest emitter, be ruled out.

The triangle’s second component is defined by having access to coal, as and when required by a country’s grid. Critically, even if a country can access coal, this may come at a steep cost (especially during a volatile supply swing), exposing citizens to government bailouts.

We recently witnessed this happen in Spain where the intermittency of renewables drove electricity price spikes, prompting government intervention and price protection. For this reason, the lack of access to affordable energy is an important metric for energy poverty. Nonetheless, the coupling of such intermittency—in winter—with coal accessibility, can have dire consequences, especially for colder-climate countries.

Lastly, the triangle’s third component leads to increased emissions. This, in turn, works against the Paris Agreement and exacerbates the current climate crisis (as outlined in the IPPC report). However, consuming more fuel also helps avoid a present-day crisis by ensuring that grids can be powered on demand.

Geopolitical Dimension of Frictional Energy

So far, frictional energy’s geopolitical consequences are arguably most pronounced in the Western Hemisphere.

In its effort to spur the energy transition, the US made declarations last year that were antithetical to the continued development of fossil fuels. However, as the Biden administration felt the friction of rising energy prices, it made a rapid reversal as it openly pressured OPEC+ to provide greater access to affordable oil.

US senators from the other side of the political spectrum had previously rebuked the Biden administration’s moves, issuing an argument that echoes the concept of frictional energy. In a joint statement, they remarked that “We find [the administration’s] request of OPEC+ [for affordable oil] to be inconsistent with stated climate objectives … [the] administration’s approach to energy production will shift production to countries with less stringent [environmental and emission] standards.”

Considering the present focus on climate change and energy sources, we can expect many more headlines and engagement that reflect the reality of frictional energy. For key stakeholders, this should drive policies and actions that shrink the triangle’s volatility.

The aforementioned is paramount, as renewables (per 2021 data from BP) only account for 5.7% of the global energy mix—which is a record high.

In sum, addressing frictional energy requires critical consideration by decision makers as renewables have substantial ground to gain, despite their current growth rate.

If we consider the energy basket to be a tool, nations can more realistically and pragmatically align their climate policy rhetoric with the reality of their energy needs. This approach reduces friction while protecting energy supply now, and well into the future.