Desperate times, desperate measures.

It's around 5 years since the oil price downturn, and we can take some comfort in the way the industry survived, adapted, and repositioned itself for growth after the last fall.

However, after all the self-help of the last oil price downturn, including squeezing the supply chain, restructuring internally, and divesting non-core assets, there is less scope for a repeat performance.

This time, discretionary spend will be firmly in focus—we expect the cuts to be hard and deep. Growth will be off the table for all but the most financially strong, or those with a mandate to maintain investment and support of economic recovery in the wake of the Coronavirus outbreak.

The first cuts will be the deepest.

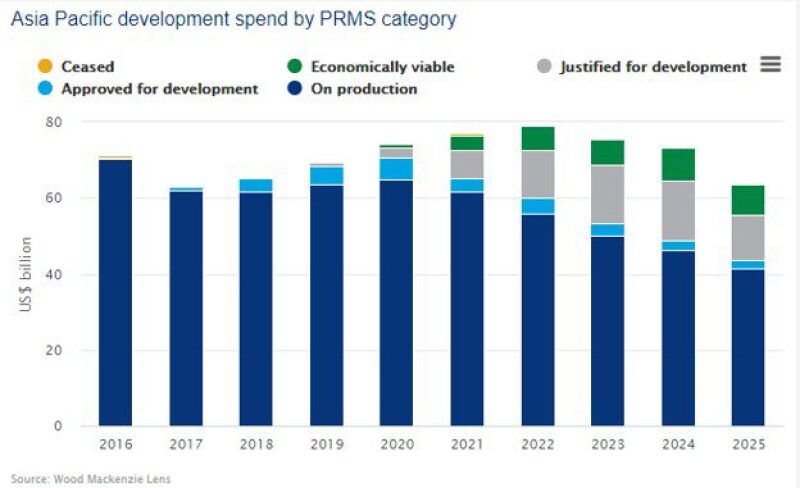

Looking closer at discretionary spend, pre-financial investment decision (FID) greenfield investments will be a key lever for companies to pull in an attempt to reduce upcoming commitments.

Australia will bear the brunt of these pre-FID deferrals, with key strategic LNG backfill projects now in real risk of being pushed back.

To illustrate how quickly things have changed, at the beginning of the year, we touted Woodside’s Scarborough and the Santos-operated Barossa development as the biggest FIDs to look for in 2020, accounting for more than 50% of the new upstream investment expected to be sanctioned in Asia Pacific this year.

However, with Santos estimated to require $60/bbl to fund growth without increasing debt levels; and 2020 revenues at Woodside set to fall by almost 40% if prices remain at current levels—neither of these companies are in a position to push the go button on these projects until there’s more clarity in the direction of the oil price.

Elsewhere in Southeast Asia, several pre-FID projects were already facing delays due to complexity and regulatory hurdles—we no longer see Petronas’ Kelidang Cluster in Brunei, and the Limbayong development in Sabah going ahead any time soon.

Only the most robust projects are likely to go ahead; Repsol’s Sakakemang development and the Jerun phase of SapuraOMV’s SK408 development benefit from low breakevens and close proximity to infrastructure. They still have a chance of being approved in year 2020.

Cuts to the Core

Now if we turn away from growth projects, cutting spend on assets already in production will become a key decision for many operators. Development drilling is one of the most obvious areas to cut. It accounts for 50% of upstream investment over the next 2 years on assets already producing.

However, many of the largest producing oil fields in Asia Pacific are mature, legacy fields requiring continued development drilling, or extensive investment in enhanced oil recovery.

Heavy investment is required to reduce production declines at the likes of China’s Daqing oil fields, Indonesia’s Rokan PSC, or even the offshore fields in the Gulf of Thailand that supply much of Thai gas demand. Reducing production declines at these projects while cutting spend will be nothing short of herculean.

Turning to exploration and mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activity, it is difficult to see it being anything other than a very difficult outlook. We expect the number of exploration wells drilled in Asia Pacific in 2020 could be 30% lower by the end of year, compared with what we had anticipated in January. Next year it could fall further if low prices persist.

Some wells, where a rig has been contracted, and partners found, could still go ahead. But in the latter part of the year, we’ll see more deferrals, including some of our 2020 key wells to watch in Indonesia, Myanmar, PNG, and Australia.

M&A activity will also be hit hard. We already saw a huge amount of oversupply as the number of assets available outnumbered the number of potential buyers. However, what has been a buyer’s market over the last year or two, is set to become a no-buyer’s market.

Small, nimble aggressive acquirers we have seen in the last 18 months will find it very difficult to raise debt in the current environment, while the financially strong operators with cash available to acquire spend didn’t get into that position by making rash decisions.

We’re likely to see much more distress in both the asset and the exploration farm-in markets—for the bold, it may pay to hold off for a few more months and find out what bargains surface.

What Does it All Mean for Oil and Gas Output in Asia Pacific?

Given the lag between investment and production, the impact on output will be muted at first.

But, if we assume all pre-FID projects are deferred indefinitely, Asia Pacific could see a 2 million boe/d reduction in supply by 2025—a reduction of more than 10% on pre-crash forecasts.

But the reality is likely to be an even bigger reduction, depending on how much operators cut investment on producing projects.