The breakeven oil price is a rough, unregulated indicator for the jagged rhythm of the unconventional oil business.

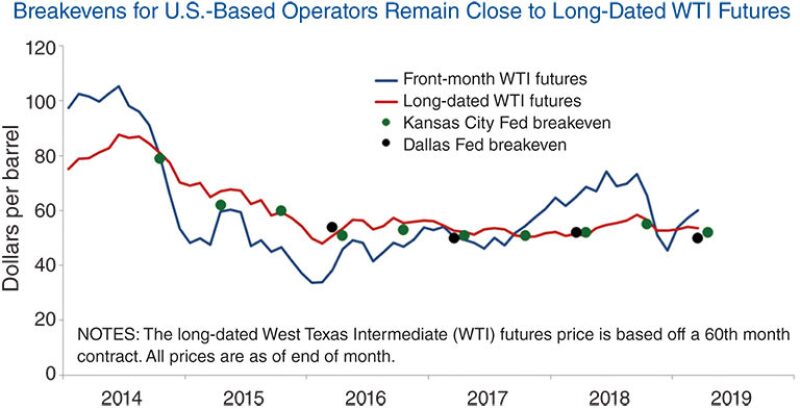

Interest in the price at which finding or producing oil becomes profitable spiked after the oil price crash in 2014 put so much production below the profitable zone.

One sign of the times was that the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas began asking oil and gas companies in and around Texas how high the oil price needed to be for them to make money drilling a well, starting in 2016.

“From our end, what we wanted is to get a feel for when a particular company will flip the switch and start drilling a new well or cut back on drilling activity,” said Mike Plante, senior research economist for the Dallas bank.

Once a year, the reserve bank asks operators to tell them what breakeven oil price is needed to justify continuing oil production from existing wells, and the price level needed to profitably drill a new well. Of the two, the drilling breakeven price has proved more useful for tracking the unconventional oil business, where constant drilling is required to maintain production.

There is a wide gap between the oil price needed to maintain production—which includes old wells in conventional fields—and the level needed to justify drilling horizontal wells with laterals that can stretch out 2 miles or more, nearly all of which are in unconventional plays.

Drilling breakeven is interesting to the bank because it is “looking for cutoffs where firms will be likely to dial up or dial down.”

When oil prices rose last year, oil and gas companies rushed to drill while profit margins were healthy. When prices fell late last year, drilling slowed. “What we are looking at now is modest growth and stabilization,” Plante said.

While these producers have benefitted from higher oil prices, productivity seems stagnant. The breakeven, which rises and falls based on production and cost changes, has shown little change in the median breakeven cost of production in the dominant US play, the Permian.

Some big expenses have gotten cheaper. Proppant prices plunged with the advent of local sand mines. The number of days it takes to drill a well has dropped and 2-mile long laterals significantly lowered the number of wells required.

But the breakeven cost “has been wiggling around $50. It has not changed much,” said Kunal Patel, associate economist at the Dallas Federal Reserve.

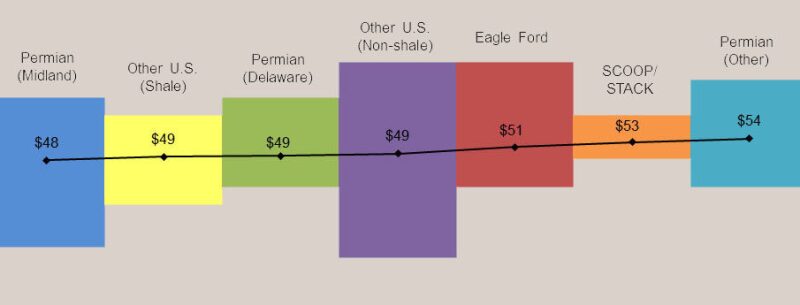

Since early 2017, the breakeven price per barrel is up $2 to $48/bbl in the Midland Basin of the Permian. To the west in the Delaware Basin, it rose $1 during that period to $49/bbl. When the survey began in 2016, it reported a $50/bbl average for the entire Permian.

Engineers seeking sustainable price reductions are up against rising day rates for services such as drilling or fracturing. Increasing production could lower the breakeven price but, on average, new wells produce less than old ones nearby and costs must be adjusted for having to drill longer laterals and fracture them more intensively.

And there is another complication: while the measure is based on the price of oil, oil wells can produce a lot of gas.

“The Permian is a bit more complicated than some of the other basins because of the high rates of associated gas and how they might be treated in well economics,” said Andrew Slaughter, executive director for the Deloitte Center for Energy Solutions.

Oil companies commonly deal with the mix by reporting production in the form of barrels of oil and its energy equivalent in gas, or BOE. In the Permian, the ratio of gas to oil rises over time, and some parts of the Permian are mostly producing gas. This matters because a company producing half oil and half dry gas is producing a BOE that is worth considerably less than the benchmark price of oil.

The volume of gas that is the energy equivalent of a barrel of oil is about 6 mcf, which in late May was worth about $15 compared with about $60 for a barrel of oil. The means that the value of a BOE that is half oil and half dry gas sells for about $38.

Many companies produce more valuable natural gas liquids, which could raise the revenue per BOE, but the shortage of gas pipeline access from the Permian means oil producers flare a lot of the produced gas because the main value is in the oil.

The Wide Range

The median breakeven price reflects a wide range. In the Midland Basin, for example, the range runs from around $20/bbl to nearly three times that price.

“There are a handful of people with really low responses that tend to be offset by a handful of people with really high numbers. There’s a lot of clustering around the average response too,” Plante said.

Some of that range is also based on the geology and engineering required to exploit it. Even within companies, breakeven prices vary significantly among the wells in a drilling portfolio.

“Every well is unique in its characteristics and flow rates,” Slaughter said. Adding to the complications is: “Breakeven estimates are dynamic over time as market and supply chain conditions change.”

Anyone collecting breakeven prices is up against a “lack of transparency as individual well costs are proprietary and not reportable” on financial reports. So while Slaughter said the numbers in this story are “completely plausible,” Patel added the qualification that they are a “little squishy.”

Squishy but Useful

The survey by the Federal Reserve Bank avoids the complications that come with breakeven calculations by simply asking sources within operating companies at what oil price it begins to make money.

Economists from the Dallas bank created the breakeven survey because they were looking for a link between current oil prices and drilling activity in the district that is the heart of the US oil business. To ensure they generated a meaningful response rate from oil and gas producers, which use a variety of breakeven methods, they did not specify how companies should define breakeven.

But a breakeven cost may not include all expenses when a company calculates its net income. It typically covers actual and expected costs as well as revenues from the moment a final investment decision is made, said Julie Wilson, director of research for Wood Mackenzie. This sort of forward-looking profit analysis does not usually include the prior sunk costs.

Top and Bottom

Since the Dallas bank’s first quarter survey, Occidental won a takeover battle with Chevron to acquire Anadarko. While the target in the bidding war has assets around the globe, shale assets in the Permian and other basins were a key piece. The takeover battle, and a round of speculation that followed about which big independent would be bought next, was fueled by the assumption that bigger companies are more likely to be profitable shale producers.

Company responses for the federal bank survey are confidential, so economists there would not describe the companies that are the low-cost producers. But they have heard that those with large holdings of contiguous acreage can drill longer laterals, reducing the number of wells, and the largest companies have more leverage negotiating service and supply contracts.

So is bigger better? “With the people we talk to, that certainly seems to be the case. Scale is important,” Plante said.