The new era of Mexican oil exploration has officially begun, but not quite as the government had hoped.

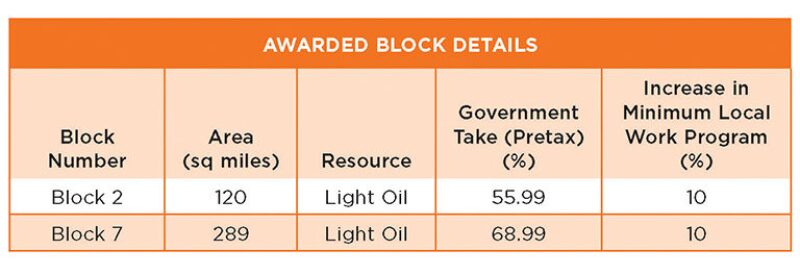

Only 2 of 14 shallow-water blocks offered in the country’s first public tender were awarded in mid-July. Blocks 2 and 7 went to a consortium led by a Mexican-based startup, Sierra Oil. Its partners are Talos Energy of Houston and United Kingdom-based Premier Oil. Just seven firms made bids in the auction that Mexican officials predicted would be significantly more competitive.

The auction was conducted by the National Commission of Hydrocarbons (CNH) in Mexico City and served as the country’s historic return to the privatization of oil and gas exploration since the industry was nationalized in 1938.

The Mexican government believed at least four or five blocks would be successfully awarded and independent estimates were as high as seven. Juan Carlos Zepeda, president commissioner of the CNH, acknowledged that the government fell short of its goal to award 30% of the blocks.

“Round One did not show the results we expected,” he said at the conclusion of the auction. “Without any doubt, an underlying factor is low oil prices, which have resulted in lower investment capacity from companies.” He added that the blocks on auction also had a higher degree of geologic uncertainty compared with blocks set for subsequent auctions. The blocks not awarded may be restructured and auctioned off in a later round.

In defending the auction results, Zepeda said the government is taking little financial risk to gain big rewards. When factoring in taxes and royalties, and assuming discoveries are made, the government will collect at least 74% of the profit share for Block 2 and at least 83% for Block 7.

“Both contracts were awarded under very positive terms for the state and that is the objective of this—to seek the highest possible income for the state,” Zepeda said.

Block 7 was the most competitive, attracting four qualified bids and one that fell below the revenue-sharing minimum. Bids on three other blocks were disqualified because they fell 5% below the government’s threshold for revenue sharing. The minimum profit share with the Mexican government was set at 40% for most blocks and 25% for heavy oil and wet gas blocks.

Sierra shares a 45% working interest in the awarded blocks. Because of technical requirements, the company partnered with Talos, which will be the operator with a 45% working interest, and with Premier, which own a 10% share.

Read Taylor, executive director of upstream exploration and production at Sierra, said the company spent a year-and-a-half working to secure the assets and was happy with the results. “These are our first set of assets, so now we have the foundation and the question is how can we effectively leverage that unique position,” he said.

Taylor added that the company was willing to be more aggressive in the auction by bidding on two additional blocks. In the end, that push proved to be more than the consortium’s other partners were willing to accept.

With regards to the outcome in general, he said the auction reflected a “weird time in the industry” where many companies are making more conservative decisions than they would have before oil prices fell.

“What we heard many times from many different players as we talked with them about potentially partnering was that the current environment was affecting them and what their boards were willing to do in a new country,” Taylor said.

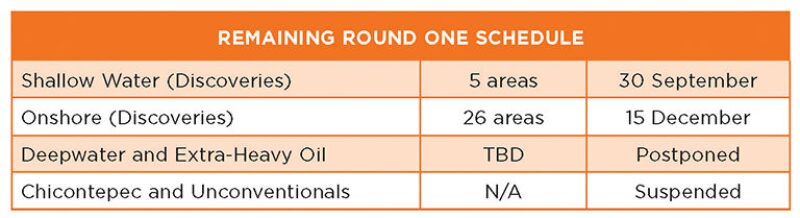

The company will participate in the next two auctions, which will include five discovered fields in shallow water and 26 discovered onshore fields. If awarded onshore assets, Sierra intends to be the operator since the qualification standards are lower. Taylor said the company is working toward becoming a shallow-water operator, which will involve sending its personnel offshore to work with Talos. “We have a lot to do to get there and that is going to happen over a couple of years,” he said.

Based on the weighted average of the Mexican government’s share and work program increase, Statoil lost out on winning Block 7 by half a percentage point. It was the company’s only bid of the auction. Helge Hove Haldorsen, Statoil’s vice president of strategy and portfolio for North America and 2015 SPE president, said the single bid reflects the fact that the Mexican opportunity is in competition with the company’s other opportunities around the world.

“If somebody bids higher, then they see more value in the block than we did and good for them. But this type of discipline is necessary if you want to have a competitive portfolio down the road,” he said.

Haldorsen praised the Mexican government on its transparency and professionalism in how it held the auction. He said that despite the lackluster results, judgment should be withheld until more auctions are held and as the drilling begins. “I do not think you can define success for Mexico based only on the opening act,” he said. “It takes more rounds and activity before you can say that this worked or did not work.”

Pablo Medina, a Latin America upstream research analyst at Wood Mackenzie, said that the figures set by the government for its share of the production profits proved to be the key differentiator. “At the end of the day, it was very close to being a success,” he said. “I think there is a lesson to be learned in terms of where they want to be putting their minimums.”

In August, CNH did revise some of the rules for the second auction to entice more bidders. The changes mainly centered on lowering the financial requirements for companies and to make it easier to form a qualifying consortium. And companies will also be allowed to make a second bid if the first one is below the minimum profit sharing threshold.

Several companies pulled out of the auction at the last minute and only seven companies and consortia submitted bids out of an expected 25. Up until the morning of the auction, as many as 18 companies and seven consortia were slated to participate.

Chevron, ExxonMobil, BG Group, and BHP Billiton were among the no-shows at the event. Several other prequalified companies announced their withdrawals less than a week before the auction. Among them were Noble Energy, Ecopetrol, and Pacific Rubiales, the largest privately held oil and gas company in South America.

A consultant, who attended the auction and asked that his name not be used because of his ties to the Mexican government, said while the results of the auction were disappointing, they were not surprising given the sentiments expressed by operators in the lead-up to the auction. He said companies were unhappy with the financial terms, including the government’s nondisclosure of the profit sharing requirements prior to the auction. “I don’t blame them,” he said. “Not only was there a threshold, which isn’t so bad, it was the secrecy of it.”

He explained that the rationale for not revealing the percentage of the government’s take until the bids were unsealed was to prevent companies from merely shooting for the minimum. CNH was pressured to pursue a high percentage of the profits largely because of the domestic unpopularity of the energy reforms that have reprivatized the industry, he said.

“These guys will be able to say ‘Hey, we didn’t give it away, and in fact, we turned away three bids,’” he said, referring to those bids that fell just shy of the profit sharing terms.

Rory Johnston, an energy economist for Scotiabank, said in his report that among the disappointing aspects to July’s auction was its failure to attract more international experience and capital. “One silver lining is that the blocks on offer in this auction were considered those least exciting for industry, allowing for changes to be made before the much more attractive deepwater blocks are tendered early next year,” Johnston said.

Just how early next year remains in question. Two weeks after the shallow water auction, the government postponed the deepwater auction without specifying a date. The government also suspended the auction for unconventional fields which was already planned to be curtailed in terms of areas on offer.

The deepwater blocks near the US-Mexico maritime border are found in the Perdido area of the Gulf of Mexico and are expected to be the most competitive because of the major discoveries made on both sides of the border.