Eighty percent of megaprojects in the oil industry fail, but the practices that lead to success are fairly well known and include

An effective stage gate process (doing the right things at the right time)

Honesty when setting the schedule and budget

Effective interface management (including external interfaces)

Management of change

Inspection, quality management, factory acceptance tests

Commissioning

As an industry we know what we need to do to succeed in our complex projects. So why don’t more projects follow those practices?

An important new book from Neeraj Nandurdikar and Ed Merrow addresses this question. The answer surprised me at first, but like many epiphanies, it seems obviously correct.

This article is a book review of Leading Complex Projects: A Data-Driven Approach to Mastering the Human Side of Project Management.

The Missing Piece—The Nature of Project Leadership

A key to project success is choosing an effective project leader. The leaders of megaprojects are usually selected from the pool of project managers who have successfully led small (less complex) projects.

The authors conclude that the skills and traits that make a manager successful on small projects, are not the skills and traits that lead to success on more complex megaprojects. We should not expect successful small-project managers to be successful at managing megaprojects—indeed it may be reasonable to expect the opposite.

The main theme of the book is that “management” of a megaproject is more an exercise in leadership than an exercise in management. Hence, management of a megaproject is a different kind of task than managing smaller projects, and successful management of smaller projects does not prepare one for leading a megaproject.

Management includes such tasks as efficient organization of tasks, rational assignment of team members and contractors, monitoring performance, and getting work accomplished.

A megaproject generally comprises multiple subprojects, each of which needs to be managed.

But the project must be led. The overall project manager (project director) needs to be a leader of leaders rather than a leader of doers. As a leader, he or she must focus on a different set of tasks such as stakeholder management, communication, and people management.

A leader who focuses on technical and management tasks to the exclusion of leadership tasks is likely to fail.

Leading is a fundamentally different role than managing. Success in managing small projects does not lead naturally to success at leading larger and more complex projects.

This is the most counterintuitive finding in the book. Management of small projects is not very good experience for leading large projects. But management of smaller projects has to be a prerequisite to leading a megaproject. What is to be done?

Impact of Complexity

Managing/leading a megaproject is a fundamentally different task than managing a small project because megaprojects are generally more complex. Complexity, rather than size, triggers pathways to failure. Megaprojects are not necessarily complex and small projects are not necessarily simple, but large projects are much more likely to be complex.

Complexity can be described in various ways. The authors chose three dimensions to define complexity (these are not independent)

Scope complexity—many distinct elements drawing on distinct technical skills

Organizational complexity—scope complexity leads to organizational complexity

Multiple teams required, organization by function, teams spread around the globe

Shaping complexity—shaping is the process by which the benefits of the project are allocated to stakeholders (consider local content requirements, for instance)

The key difference between simple and complex projects is interconnectedness. In a complex project, a minor change in one part of the project may have a significant impact in another part.

Impact of Leadership

The authors provide anecdotal evidence of how critical leadership of a project is.

“Turnover of leadership in complex projects is devastating to the economics of the project. The projects with no turnover of project leadership lost about 50% (median) of their promised net present value (NPV) between authorization and realization, but about 60% were still profitable. The projects with turnover lost 105% (median) of promised NPV and less than a quarter were still profitable.”

Methodology and Data

The authors identified 100 recent large projects and sent questionnaires to leaders of those projects. Fifty-six responses were received; 40% of those were from failed projects.

The questionnaires were designed to identify/measure the project managers’/leaders’ personalities, emotional intelligence, and leadership style. These traits were then compared to the success/failure of their projects.

The questionnaire was based on:

- The Five-Factor Model (Big 5)

Openness

Conscientiousness

Extraversion

Agreeableness

Neuroticism (emotional stability)

The Emotional Intelligence Scale, which measures how a person recognizes and uses their own emotions and how well they identify the emotions of others

The hedgehog-Fox Index (from the metaphor popularized by Isaiah Berlin; foxes are big-picture thinkers and hedgehogs are specialists who focus on one big thing)

Leadership Style Index (based on Primal Leadership)

Visionary

Coaching

Democratic

Pacesetting

Commanding

In a previous study the authors studied managers of smaller projects, so they have data to compare the traits of successful and unsuccessful small and large project managers.

Unique Demands on Leaders of Megaprojects

As project complexity grows, line-of-sight management becomes increasingly impractical. The manager of a complex project is a leader of leaders. Leading leaders is a very different undertaking than leading doers.

Scope complexity requires that the project leader be a generalist with knowledge of the major project functions, including reservoir, wells, facility, operations, and commercial. The central shaping activity is stakeholder management. Shaping complexity adds new realms of work in politics, diplomacy, negotiation, and economics. Surprises in shaping can render a project much more complex.

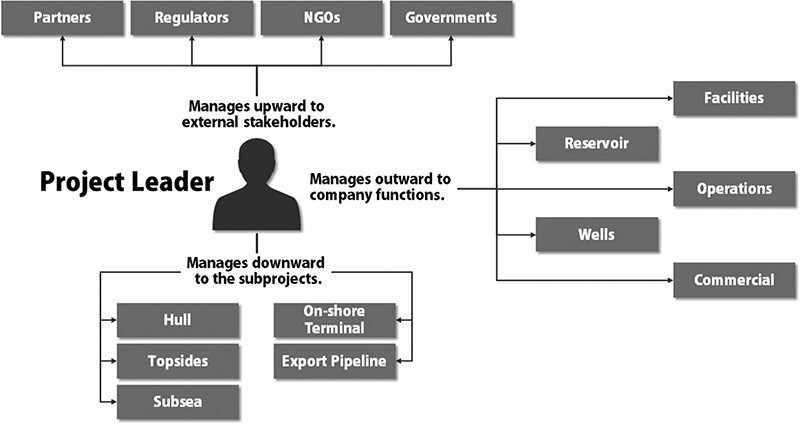

The figure shows the three distinct levels of management/leadership involved in shepherding a megaproject.

There is the usual challenge of managing downward. There will be subprojects, each with its own project manager. Each of these subprojects must be aligned to the overall goals.

The second level is managing outward to the internal stakeholders such as technical specialists.

The third level is managing upward to the external stakeholders. Stakeholder management requires a set of soft skills that would often challenge even an experienced diplomat.

Traits and Skills of Effective Project Leaders

Successful project leaders are foxes, not hedgehogs.The single question that most accurately separates successful from unsuccessful leaders is

When a significant problem occurs on a project would you rather

Identify a solution quickly and then plan its execution in detail (hedgehogs è failure)

Try to identify all possible solutions and then implement your chosen solution quickly (foxes è success)

Cost performance

Foxes: 0 % average cost growth, + 20% (std. dev.)

Hedgehogs: 30 % average cost growth, + 30% (std. dev.)

Most foxes started their careers as successful specialists and became generalists via varied experiences over the course of their careers.

Emotional Measures of Engineers

Respondents were rated on five personality scales: openness, agreeableness, extroversion, neurotic/stable, and conscientious. Engineers in general are more conscientious, but much less open than the general public. In particular, artists are much more open than engineers.

Only one of these scales was significantly correlated with megaproject success. Successful megaproject leaders are significantly more open than unsuccessful leaders. But openness is not significantly correlated with success at managing small projects. To repeat: Leading a megaproject is a fundamentally different task than managing a small project.

Emotional Intelligence Scales

Emotional intelligence does not play a large role in success or failure on smaller projects. But there are important differences between successful and unsuccessful megaproject leaders in four areas:

Recognizes one’s own emotions

Optimism

Social skills

Recognizes other’s emotions

What types of previous experience are beneficial?

Nonoperated venture. Experience representing a partner in a nonoperated venture is significant.

Hookup and commissioning experience is significantly correlated to successful project leadership.

Business experience is detrimental to success.

Leaders’ Views of Tasks

Summary of What Leaders Considered Important and Where They Spent Their Time

Task Category | Leaders That Consider Task To Be Important | Leaders That Spend More Time on Task |

|---|---|---|

Stakeholder Management | Successful Leaders | No difference |

Project Work Processes | Unsuccessful Leaders | Unsuccessful Leaders |

Project Controls | Unsuccessful Leaders | Unsuccessful Leaders |

Project management | No difference | No difference |

Communication | Successful Leaders | No difference |

People Management | Successful Leaders | Successful Leaders |

Contractors and Vendors | Successful Leaders | Successful Leaders |

Engineering/Technical Tasks | Unsuccessful Leaders | Unsuccessful Leaders |

Construction Safety | No difference | No difference |

Unsuccessful leaders are downward-focused, spending their time and energy on technical or hard-side tasks such as work processes, project controls, and technical problems. Successful leaders spend their time and energy on soft-side tasks such as stakeholder management, communication, people management, and contractor and vendor interfaces.

Personality, Emotional Intelligence, and Leadership Styles

Nandurdikar and Merrow conclude that we are choosing the leaders of megaprojects via the wrong metrics. Success in managing small projects is not sufficient; indeed, the traits that naturally lead to success in small projects management lead directly to failure in megaprojects.

Choosing project leaders with the right personality and emotional intelligence is critical to project success. In the words of the authors:

“The behavior of project leaders may be shaped somewhat by skills and training, but it is clearly modulated through personality and emotional intelligence. Those with more closed personalities and lower emotional intelligence tend to emphasize work process and technical tasks and shun the people-to-people tasks. That is just natural. But the people tasks are what generate success, especially in the complex projects where transactional management cannot work.”

For those who may be skeptical of the analysis, Part 2 of the book has seven leaders, who discussed on record their leadership journeys. They confirm the data and also show the stability of the hypothesis: There are certain personality traits, habits of mind, and tasks that drive success, no matter if you are a woman or man, from an international operating company, supermajor, or national oil company, be it from the Western or Asian world.

Howard Duhon is the principal engineering advisor at GATE. He is a former SPE Technical Director of Projects, Facilities, and Construction and is a member of the Editorial Board of Oil and Gas Facilities. He may be reached at hduhon@gateinc.com