Even before a pandemic changed the course, the oil and gas industry was destined for big change, thanks to pressure coming from a number of different fronts.

The asymmetric challenges include the industry’s dire need to get caught up on the digital transformation while also figuring out how to embrace the separate arena of low-carbon technologies.

Representing the human embodiment of this juggling act is another new challenge: Generation Z.

Born between 1996 and 2010, Generation Z—or Gen Z, or the plural, Gen Zers—represents one of the clearest signals that the great crew change has come and gone. Yet, big questions remain about whether oil and gas companies and the academic programs that feed them talent have fully adapted to this reality.

Three new technical papers recently presented during the 2020 SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition (ATCE) suggest that the answer is no.

However, what the papers also suggest is that there are clear steps that industry can take to become a more attractive one to the youngest generation of workers.

The most common thread between the papers is the call for major reforms in how petrotechnicals of the future are educated at school and trained at work.

Putting the scope of the generational gap into clearer context, one of the papers from professors at the Australian College of Kuwait found that Baby Boomers (those born from 1944 to 1964) make up only 6% of the current industry workforce. Meanwhile, about a quarter of all employees are Generation Z.

The following is a selection of the actions upstream companies and petroleum engineering departments are being told will help them adapt to the technological and generational shifts that are redefining the business.

To Lead Gen Z, Think Like Gen Z

To appreciate Generation Z, one must first understand why they are different from generations of past. Two chief characteristics that stand out to Maria Capello is that Gen Z is driven by community and dialogue.

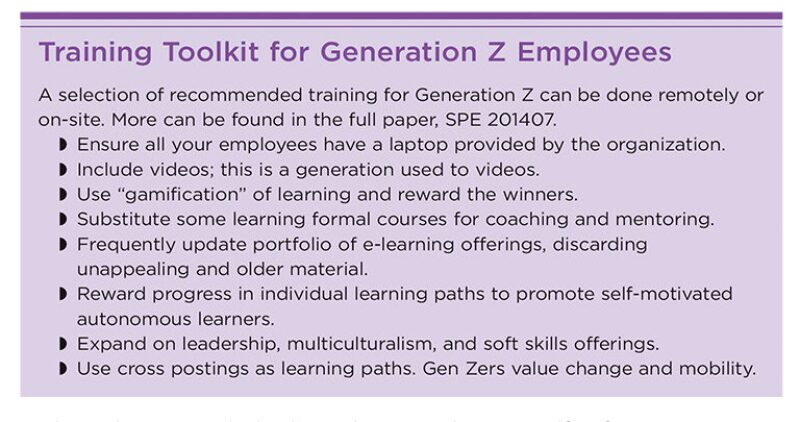

Capello, an industry consultant and former executive advisor at the Kuwait Oil Company, notes in her new paper (SPE 201407) about the industry’s talent development of Gen Z that lacking such awareness risks creating “yet another unconscious bias that could affect hiring, onboarding, training, performance evaluation, and motivation workflows at work.”

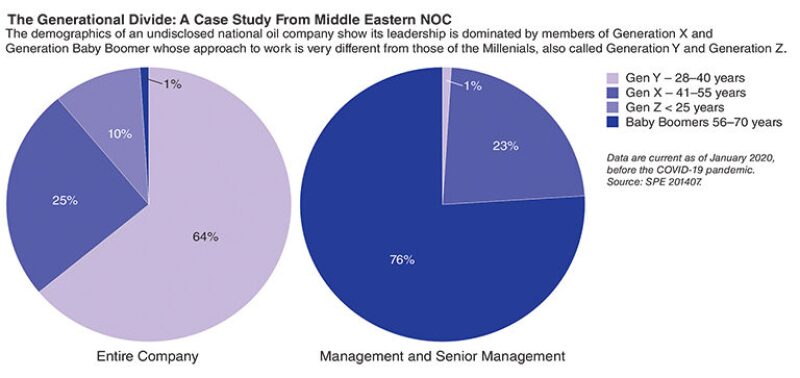

Her paper features a case study that explores the generational shifts taking place at an unnamed national oil company (NOC) in the Middle East. The operator’s name has been shielded, but Capello and her coauthor believe its experience draws parallels with other NOCs and international service companies.

Done in January, before the global pandemic caused industrywide contractions, the study showed that just under 10% of the NOC’s employees were part of Gen Z. Combined with Generation Y—or millennials—nearly three-quarters of the company was 40 or younger.

Another 24% belong to Generation X, while only 1% were classified as Baby Boomers.

Employees from the latter two age groups accounted for 99% of the company’s management.

“That means, as expected, the whole of management has a different mentality, approach to life, values, and styles than the very workforce they need to lead,” said Capello, who included in her paper a list of recommendations on how leaders can adapt.

Since Gen Z are the truest digital natives, having never lived a day without the internet, many of the recommendations reflect a need for the industry to improve its digital appeal.

This includes simple steps such as ensuring every employee has a laptop. And when it comes to social media, on which Gen Z is omnipresent, it’s not just companies that should have active accounts, but its leaders should too, Capello recommended.

She also stressed that companies need to invest in replacing their libraries of training videos and e-learning programs since they risk appearing dated to the tech-savvy Gen Zer. “Discard those at all times, they will not be useful even if they have valuable content,” she said. “The style had to be modern, the delivery method has to be updated.”

This all feeds into the central argument that it is critical for older generations of leaders to connect with Gen Z by finding ways to not just relate to them, but to trust them.

That may mean accepting nontraditional work styles. For example, older generations may prefer to hold brainstorming sessions at the conference table or over a coffee in the break room. Gen Zers tend to opt for online collaboration that can be done anytime, anywhere.

“We need to get used to Slack, to WhatsApp, and to other platforms that enable this kind of modern communication,” emphasized Capello. “It’s not informal anymore, it’s the very essence of communication nowadays.”

In case all this sounds a little one-sided, older generations still have plenty to bring to the table. Capello remarked that Gen Zers are “surprisingly old school” and still place great weight on the industry’s “classical, prestigious certifications” because they know these are universal qualifiers of their talent—a characteristic oil companies should seek to foster.

The youngest group of workers also values the expertise of those who came before, something Capello said should encourage companies to “not shy away from bringing in retirees as coaches or mentors, especially those who are revered.”

Petroleum Engineering, Plus Something Else

Many of the other problems facing the industry’s generational shift stem from the universities, which by and large, are much further behind in technology adoption than oil and gas companies.

The traditional route to a petroleum engineering degree starts with taking a mélange of basic college courses that include everything from history to biology. Only after 2 years are most students ready to move onto the core disciplines.

Upon graduation, only 20% of the coursework will have focused on nontraditional topics, which these days includes machine learning, sensor fusion, and advanced robotics.

Robello Samuel, a technology fellow with Halliburton, said in his paper (SPE 201755) that this classical pathway to an engineering degree is “outdated.”

“Current petroleum engineering students have little idea about how the business is carried out [or] how the industry is getting evolved,” he said during ATCE, adding that his estimation is that petroleum engineering programs have changed little over the past 25 years.

This has left many programs out of step with the digital transformation that is sweeping through much of the industry. Without a corresponding modernization of the industry’s educational core, Samuel believes the industry risks finding the talent required to modernize itself. “If we’re not assimilating, we end up falling flat,” he said.

In the wake of the 1980s oil bust, the industry emerged with new tools such as measurement while drilling that soon proved critical to ushering in the age of the horizontal well. Likewise, the 2014 price crash resulted in the industry’s headlong dive into the digital transformation which has demonstrably lowered the number of people oil companies require to produce each new barrel.

Samuel said the next bifurcation point will lead to the maturity of automated drilling. However, as he noted, this is not guaranteed since most drilling engineering courses continue to ignore recent advances in automation, robotics, or intelligent downhole tools.

Among the top recommendations offered is that university programs flip the curriculum pyramid to leave more room for the nontraditional but increasingly relevant subject matter.

Without compromising the teaching of engineering fundamentals, Samuel said petroleum engineering departments should take “the digital transformation approach and infuse a lot of information and a lot of topics” into their programs to make them more practical and integrated.

By adopting a multidisciplinary focus that builds atop petroleum engineering, new graduates would bring more value to the industry and stepwise benefit from being more attractive hires, Samuel added. For instance, in addition to graduating as a petroleum engineer, more students in the future could at the same time become proficient in building cyber-physical systems to drive innovation in automated drilling.

The Energy Engineering Degree

An increasing number of oil and gas producers around the world are seeking to offset their role in climate change by investing in technologies that can help curb it, such as emissions-mitigation systems, integration with renewable-energy systems, and CO2 sequestration.

This has increased demand for people with “new competencies to develop cleaner production processes and to take advantage of existing more environmentally friendly energies to create a symbiosis capable of improving greenhouse-gas emissions at a reasonable price,” explained Herminio Passalacqua, an associate professor of industrial practice at the Australian College of Kuwait.

Demand may be there, but he points out that the supply is not.

Passalacqua said while presenting his paper (SPE 201593) that as oil and gas companies look for people who can help make their operations a bit greener, so too are other big industries, which means the hiring competition will only intensify in the years to come.

Portending more difficulties, most petroleum engineering departments around the world have been shrinking since 2015 due to a lack of jobs and falling starting salaries. Passalacqua concluded that enrollment will continue to suffer due to “the growing environmental awareness among young people.”

One way to address these issues is to consider turning a petroleum engineering degree into an energy engineering degree—or at least big pieces of it. Other options include offering more business skills like teamwork, project planning, and corporate communications.

Despite becoming increasingly important, Passalacqua said most petroleum engineering curricula are devoid of courses on environmental sustainability, the wider energy system, or business administration. There are a handful of exceptions he would like to see expanded, including the Colorado School of Mines which offers petroleum engineering as a minor in energy engineering. The research university describes the program as one that “not only addresses the scientific and technical aspects of energy production and use but its broader social impacts as well.”

In the end, a more diverse educational background may prove to be equally advantageous for petroleum engineers who are entering the industry at a time when peak demand is predicted to be only 10 to 20 years away.

The paper highlighted that the opportunity to indulge in broader energy system courses “offers more flexibility and options when looking for a job, especially in those periods of low fossil-energy prices.”

For Further Reading

SPE 201407 Considerations and New Approaches for Talent Development of Gen-Z in Oil and Gas by Maria Angela Capello and Bashar Al-Khashti, Kuwait Oil Company.

SPE 201593 Energy Transitions: An Academia Take on Shaping the Future Professionals of Oil and Gas by Herminio Passalacqua and Mortadha Turki I Alsaba, Australian College of Kuwait.

SPE 201755 Rise of Machines: Time to Change the Petroleum Engineering Curriculum by Robello Samuel, Halliburton.