Last summer, while being moved from one well pad to the next, a rig in the Delaware Basin of Texas was updated with some new software. It took 11 hours to complete, and after the rig was powered back up, it went on to drill the vertical section of a horizontal well almost 3 days ahead of schedule.

Aside from boasting an impressive stat line, that well represents an important milestone for National Oilwell Varco (NOV) because it is the first to be drilled using the company’s closed-loop automated drilling system in conjunction with a recently launched rig operating system, which the company technically refers to as a process automation system. NOV is telling customers that this technology not only lowers the cost of field development, but delivers higher quality and straighter wellbores through its consistent performance.

That automated program in Texas has concluded, but the combined technology package is now being used to drill shale wells on four rigs in the US and one in Canada. There are 16 separate orders for the new process system. These contracts for NOV follow more than 5 years spent using the hardware kit, which includes wired-pipe and a weight-on-bit controller, to drill through more than 2.5 million ft of conventional and unconventional formations.

Going forward, the oilfield technology developer is offering a more complete product: automation controlled by highly capable software. This integration means that the digitally connected surface and subsurface machines working on an automated rig now have a digital driller to take orders from.

“Our mantra is that the rig of the future is here today—just add software,” remarked Tony Pink, the vice president of strategic sales at NOV. Pink has been involved in the automation initiative at NOV since its genesis and coauthored a recently published technical paper (SPE/IADC 184694) detailing the Texas project that it carried out with Calgary-based Precision Drilling and an unnamed oil and gas explorer.

He described the tandem of NOV’s automated hardware and software as “a sophisticated autopilot for rigs” that takes many routine tasks out of the driller’s hands—literally. With the process system in control, drillers can lay off the joystick, stop pressing buttons, and also quit staring at screens in order to maintain their drilling direction.

Instead, with key rate-of-penetration parameters such as weight on bit taken over by the system, drillers become overseers of the well construction process. This frees them up to pay attention to improving crew productivity and safety. Pink put it this way: “You are moving them from being a machine operator—a crane driver effectively—to being a driller again.”

Small Gains Add Up

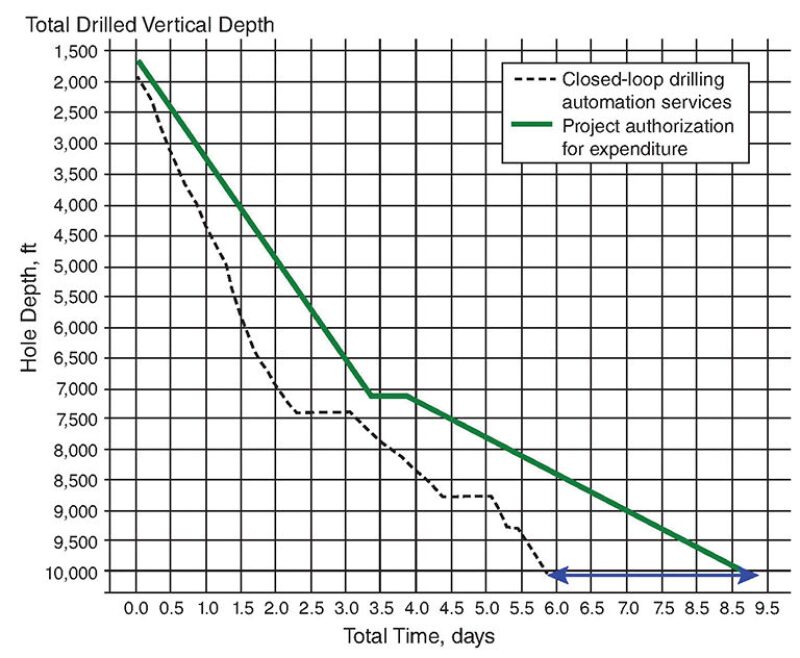

The paper focuses on a single well that had an approved drilling schedule for the vertical section of 8.7 days but reached a total depth of about 10,000 ft in 5.9 days, saving 2.8 days of rig time. This performance gain was the result of multiple automated elements, and includes efficiencies that were only realized by using the process system.

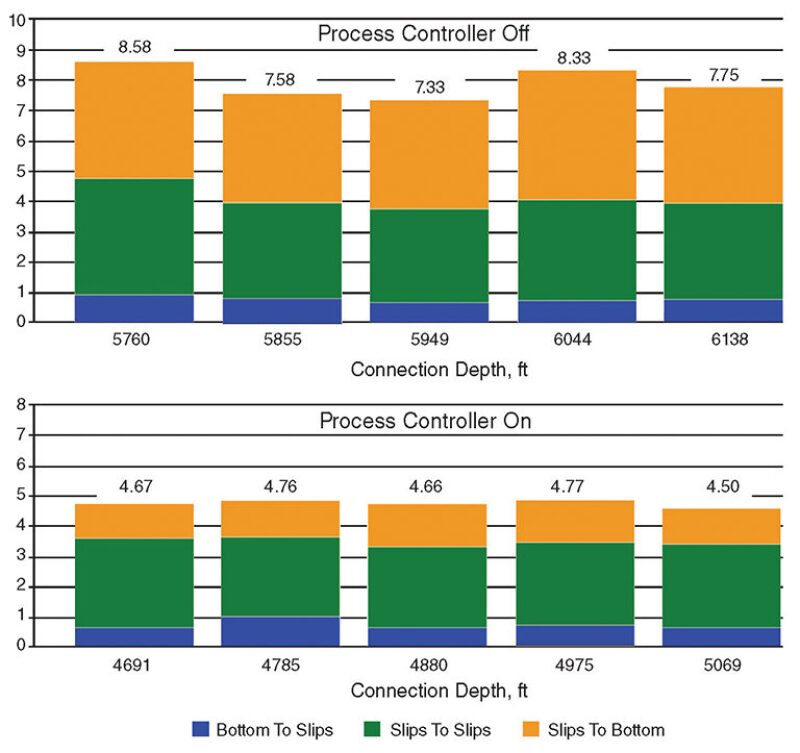

One of them was a reduction of drillstring connection times by an average of 3.24 minutes compared with manually controlled times. With an average of 80 connections made for the intermediate well section, the only section the paper covers in this regard, the saved time adds up to more than 4 hours. Though in total, there may be more than 300 connections made for the entire length of a modern horizontal well.

Contractor Embraces Automation

The inclusion of this technology in Precision Drilling’s premium services on its tier-one rigs reflects a new priority for what is one of the world’s largest drilling outfits. Duane Cuku, the vice president of sales for rig technology at Precision Drilling and coauthor of the paper, said the firm is able to embrace automation on a commercial scale for the first time because of the way the new process system works.

In earlier experiences with automation, he said the company saw clear challenges in expanding its use of the technology because the number of native operating systems, and different versions of them, installed on its rigs made reprogramming them too laborious and impractical.

“The real change for us today is having a standardized platform, one that gives us leverage to effectively deploy software improvements across the entire fleet,” said Cuku. “Historically, to upgrade software, you would have to go out to each drilling rig, take it out of service for a period of time, and have a technician work on its base control set.”

This is no longer the case with the new process system, which requires no changes to the rig’s existing operating system. Rather, it sits on top of the native system and works within the rig’s technical limits. It is also able to identify which automated components are available to work with, which, importantly for uptake, may be ones developed by NOV or other companies.

This agnostic approach makes it possible to use the process system on all types of rigs without concerns over compatibility issues. And as Cuku pointed out, it also benefits drillers by giving them a user interface with the same look and feel regardless of which type of underlying control system is in use.

Capturing Lessons From Downhole Data

Pink noted that though the hardware has a longer track record—and much more is known about it through several published papers—the automation software was being designed in parallel the whole time. In those past case studies, of which only the automation hardware was used, operators did see some significant performance gains but they also faced problems in dealing with the amount of raw data streaming out of the system’s different components.

“Not only were they getting a firehose of data,” Pink said, “but they had no structured way of taking those lessons learned, capturing them, and then passing them out into the field.” With the process system, he added, drillers and operators now have something that helps them use the technology more effectively, and at scale.

In the upcoming automated drilling projects all the downhole data will be organized by formation and loaded into the rig’s process system. That information will be used to optimize the software-controlled drilling of subsequent wells facing similar geologic conditions.

Pink emphasized that this does not involve emerging artificial intelligence or machine-learning techniques. “This is about humans learning,” he said, explaining that the drillers will be responsible for providing the input needed to update new learnings into the process system.

Mention of the human role raises another point on the degrees of automation at play here. This system is considered semi-autonomous because it relies on skilled people to improve its abilities, and if a correction is ever needed, it can be superseded by the driller by simply grabbing the joystick.

One key part of this data initiative will depend on the success of NOV’s app store approach to the process system. Just like smartphone makers, the firm is allowing third-party developers that could include majors, service companies, and startups to add value to its product with their own add-on features.

So far, there are five core apps that come preloaded on the control software to handle basic routine tasks such as controlling the speed of “tagging bottom” with the bit. Two outside apps are also under development. The company is also making an effort to drive down the cost of its wired drillpipe, long seen as a barrier to the wider use of downhole automation. Pink said the aim is to reduce the price differential with conventional pipe enough “to where it’s no longer part of the discussion.”

Consistency and Cadence

As has been seen in other heavy industries, the consistency of automated machinery has the effect of lifting the performance of workers by making their jobs more predictable. The improvement in connection times achieved with the process system is one example of this.

On most automated rigs today, a new joint of pipe is still added to the drillstring by hand, which introduces room for unavoidable randomness in the speed at which they can be screwed together. But Cuku said, “If the machine sets the stump at the exact same height each time, the wrench doesn’t need to be adjusted and the crew knows how long that will take, because the time spent coming-off-bottom and into the slips is now standardized.”

He added that as the “crews on the floor get into a cadence with the machine,” that the consistency in such routine tasks becomes clear to see in the data. One chart comparing the best five connection times made by the process system and those made by a driller Cuku described as “very competent” does not even have to be labeled to tell which is which. The process system’s set of times are very even, while the other times are noticeably uneven and significantly longer.

Such examples represent only the low hanging fruit of potential drilling efficiencies, Cuku said, who added, “With a platform like this, you can deploy any number of optimization applications.”

But new tricks will require more downhole data and that could be coming soon. Earlier this year, Precision Drilling announced that automation upgrades will be part of a USD 52 million capital expenditure program. Dozens of rigs will be included in this plan; however, the number to be equipped with automated technology was not specified.

In a separate project, and unrelated to the NOV partnership, Precision Drilling is aiming to de-man its directional drilling service with an automated advisory system (SPE/IADC 184682). Cuku said that this technology was tested in passive mode on hundreds of wells and has recently been used in active mode to drill the curve on several wells.

For Further Reading

SPE/IADC 184694 World First Closed Loop Downhole Automation Combined with Process Automation System Provides Integrated Drilling Automation in the Permian Basin by T. Pink, D. Cuku, S. Pink, NOV et al.