Stories about the future of the North Sea oil business often talk about this pioneering offshore basin in the past tense. A recent one from the Petroleum Economist, headlined “Growing old gracefully,” described the future there as “squeezing out the last drops.”

The global oil and gas industry is feeling the pain of the oil price plunge, but the UK feels it more acutely. Exploration drilling is at rock bottom levels, the offshore UK Continental Shelf is one of the world’s most expensive from which to produce a barrel of oil, and investment spending is expected to drop sharply in coming years. When it comes to new technology development, the North Sea is known as a global testing ground for advances in well plugging and platform removal.

The pessimistic talk has served as a rallying cry for much needed change. “Do not waste the crisis,” said John Pearson, who chairs the Efficiency Task Force created by the industry group, Oil & Gas UK, to seek ways to lower the cost of North Sea exploration. “We have got a golden opportunity. Let’s not waste it.”

He delivered his call for action at a presentation at the recent SPE Offshore Europe Conference & Exhibition in Aberdeen where Oil & Gas UK released its 2015 economic report that showed the problems there go deeper than the oil price collapse.

“If there was no action, it [North Sea output] would shrink. But the plan is to take concerted action,” said Angela Seeney, director of technology, supply chain, and decommissioning at the Oil & Gas Authority (OGA).

The authority was created this year by the UK government as part of an effort to revive North Sea exploration and production. The actions also include significant tax reductions, and free, high-quality seismic images of frontier areas. The OGA has a dual mandate of regulating the business and maximizing the ultimate recovery of the country’s oil and gas reserves.

The call for change began before the collapse of oil prices with the release of the Wood Review early last year. The report warned that the UK offshore industry could face “irreversible damage” if prompt action was not taken to address its problems. Since then, the government and the industry have taken a rapid series of actions to follow the report’s recommendations to ensure the maximum economic recovery of North Sea reserves.

“You tend to think that regulators regulate, and we do,” Seeney said. Its mandate also calls for promoting cooperative efforts to maximize the ultimate oil production by reducing operating costs, driving innovation, and promoting exploration.

Gloomy Report

A close look at the state of the industry underlines the gravity of the situation. While there are projects now putting fields into production and increasing the output of older ones, the long-term indicators are negative.

Oil & Gas UK said last year there were 14 exploration wells drilled, the lowest number “since exploration on the United Kingdom’s continental shelf began in 1964.”

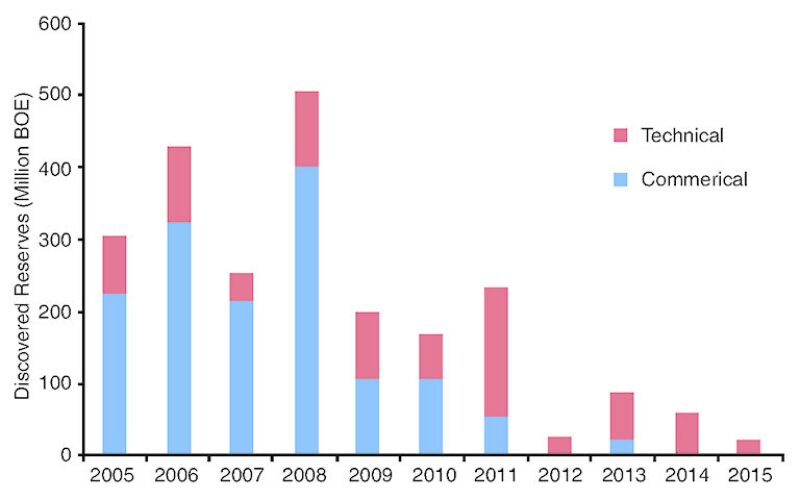

“We are not drilling many wells now and what is more alarming is the lack of exploration success,” said Adam Davey, economics and market intelligence manager for Oil & Gas UK. In the past 7 years, the size of the fields discovered on the UK Continental Shelf have been less than 100 million BOE.

The outlook is better in the short term. During the first 6 months of the year, production was up 3%. This year is expected to be the first in 15 years to show an increase with a handful of major field development projects in progress.

The rise in production is a product of a 4-year-long surge in offshore investment spending fueled by oil prices that regularly exceeded USD 100/bbl. That run peaked in 2014 at USD 22.5 billion for development projects, which will add 15 new fields this year and next.

Spending this year is expected to drop to between USD 15 billion and USD 17 billion, and fall further from there. Past experience has shown that low investment leads to declining oil and gas output several years later.

The big spending years are now described as a period of excess. A chart from the Oil & Gas UK shows that while spending surged from 2010 to 2014, cash flow slid every year, slipping into negative territory over the past 2 years. Deirdre Michie, chief executive of Oil & Gas UK, offered that fact as evidence that “we need a major reset in the industry’s collective thinking.”

The largest ongoing North Field development projects according to Oil & Gas UK are listed below.

Quad 204

BP

A USD 4.6 billion project to rejuvenate the Schiehallion and Loyal fields west of the Shetland Islands with an extensive drilling program; replacement of an aging floating, production, storage, and offloading (FPSO) vessel, and upgrading the subsea equipment.

Clair Ridge

BP

A USD 6.9 billion project to develop Clair Ridge, north of the previously developed Clair Field. Two linked platforms will be installed. It will be the first use of BP’s low-salinity enhanced oil recovery method to maximize production in a field which that has an estimated 640 million bbl of recoverable resources.

Mariner

Statoil

Offshore platform installation has begun on the more than USD 7 billion project to produce heavy oil from a North Sea field holding an estimated 250 million bbl of reserves. The field was discovered 30 years ago but was not developed because of the difficulty of producing the viscous crude.

Laggan-Tormore

Total

A USD 5.4 billion project is developing two fields producing gas and liquids in the deep waters west of the Shetland Islands using a subsea production system connected directly to an onshore processing plant by a 143-km pipeline. Total’s Edradour field will be tied in as part of the plan to add production from other nearby fields.

Catcher

Premier Oil

Construction has begun to develop the Catcher field and two nearby fields. At a cost of approximately USD 2 billion, the project will use an FPSO designed for rough sea conditions as a production hub. First oil is expected in 2017 and there are plans to tie in other nearby fields.

Kraken

EnQuest

A USD 4 billion project to develop three heavy oil fields holding an estimated 140 million bbl of reserves east of the Shetland Islands. First oil production from the 1985 discovery is expected in 2017 using an FPSO, which will offload the crude into tankers.

The problems and the required treatment are not unique to the North Sea. Offshore explorers around the world are having to adjust their businesses to profitably develop ever smaller discoveries, often in lower-quality reservoirs that are more difficult to produce. Low oil and gas prices add to the pressure to cut costs.

“There has been a radical cost increase not only in the UK, but globally,” said Tove Stuhr Sjoblom, senior vice president in charge of Statoil UK, during an Offshore Europe panel discussion.

The issue is more of a concern in the UK North Sea because it is, by far, the highest-cost offshore basin among 10 measured by Oil & Gas UK, based on the average cost of lifting a barrel of crude.

“The problem is not the oil price, though it is deeply unhelpful. This was a problem we were looking at a year ago before oil prices fell. We have become very inefficient,” said Pearson, group president for Northern Europe and the CIS (former Soviet republics) for Amec Foster Wheeler.

One way to lower the average lifting cost is to find more oil and shut down the least efficient facilities. The lifting cost per barrel on the UK Continental Shelf ranges from less than USD 8, for generally newer fields, to more than USD 90, for often older platforms that are costly to maintain and produce a fraction of what they are designed for, according to Oil & Gas UK.

Higher costs make it hard for the UK to compete for a piece of reduced exploration budgets. “Our costs in Asia are lower in every aspect compared to here,” said Robin Allan, director of North Sea exploration for Premier Oil, an independent based in the UK with a large stake in the North Sea.

Operating costs in the basin are expected to drop by 22% by the end of next year, according to Oil and Gas UK. But this decline is largely a product of concessions by suppliers responding to operator demands, which are happening worldwide.

“We have not reduced costs in this basin to where it is economically viable going forward,” Allan said. “Unless collaboration goes to a whole new level, I do not see a particularly optimistic future in the North Sea.”

Pearson said cost cutting is now in the first, and easiest stage. There is a limit to supplier discounts, and those will disappear when business comes back. Deeper, lasting cost reductions will require years of work. Building in efficiency will require difficult adjustments, such as simplifying the contracting systems, standardizing equipment designs, changing how projects are managed, and introducing new technology to improve results.

“These things can be done, but they are a personal choice. If we do nothing, then the future is really bleak,” Pearson said.

Pushing Change

The rapid action to reduce taxes on offshore oil and gas and create the Oil & Gas Authority is an indication of the critical role the North Sea oil production plays in the UK economy. The industry supplies half the oil and gas used in the country and creates 375,000 jobs directly and indirectly through its spending.

The agency’s name proclaims it is an authority, and it does have the power to levy large fines. But when asked how the OGA will use its power, staffers respond by discussing its role as a catalyst for change.

Production growth is a top priority, but the authority cannot order companies to drill. To encourage exploration, it is spending USD 30 million for a massive seismic survey of two little- explored areas. It needs to coax the industry out of its exploration comfort zone near operating hubs. While the cost of bringing production on line from nearby wells is modest, so has been the size of the discoveries.

Technology development is also a part of the plan to change the perception of the basin by commercializing new ways to achieve “maximum value at lower cost and risk” at each stage of a field’s life, Seeney said.

Doing so in the North Sea will require working a puzzle with multiple interrelated variables. Many fields are clustered in a relatively small area of the North Sea where solving one problem can create others.

For example, one of the OGA’s biggest challenges is dealing with the massive structures on fields where operators are losing money because oil and gas production has slowed to a trickle. Removing those facilities, though, could block new development. The Wood Review warned that removing old platforms would leave gaps in the pipeline system that runs from platform to platform.

The authority’s powers include the right to sit in on company meetings and obtain operating data. An important job is resolving disputes between the companies that want to remove money-losing production platforms and smaller players whose future depends on their ability to connect to existing platforms.

The authority is also working with the industry to address a shared financial problem, the potentially huge cost of removals. The government pays from 50% to 70% of the cost of shutting down oil wells and removing platforms and pipelines. The OGA estimates the total expense at USD 47 billion to USD 71 billion, depending on how efficiently the work is done.

The nearly 35% cost reduction, if decommissioning is done at the low end of the range, is right in the middle of cost reduction goals for a variety of operational efficiency task forces seeking savings from 30% to 40%.

Operators will be required to engage in a long-term planning process aimed at maximizing the ultimate economic output. A lot can be gained by managing the process. One goal is to spread out the platform removals to avoid demand spikes that push up prices.

The OGA is asking companies to work together on campaigns to remove multiple wells and platforms. Eight operators in the southern North Sea area have agreed to share information on plugging and abandoning about 500 wells, which will hopefully lead to joint projects. The authority said the experience gained by companies that have done six or more wells can reduce the cost by up to 40%.

While it searches for ways to lower the cost of decommissioning and other aspects of offshore operations, any possible solutions must also lower the hazards associated with these operations, from workplace accidents to environmental damage. The authority, which is funded by an industry fee, will be backing a wide range of technology research and development projects.

“Decommissioning is only one part of the story. We have got to find ways to enhance exploration and production or there will be insufficient growth,” as older wells play out, said Seeney, who joined the authority after a career with Shell in a variety of technology and product development roles.

Growth Areas

The OGA’s strategy is to promote growth and maximize recoveries, not manage the graceful retirement of the North Sea. While the recent exploration results in UK waters have been meager, a large discovery nearby in Norwegian waters shows that drilling in heavily explored areas can still be rewarding.

Just east of the international boundary, Statoil discovered the Johan Sverdrup field holding from 1.3 billion bbl to 3 billion bbl of recoverable oil in a place that had not been drilled in decades.

“I still think there are areas to be found. It may not be as big, but they are out there” in the North Sea, said Øivind Reinertsen, a senior vice president for Statoil, at a conference briefing.

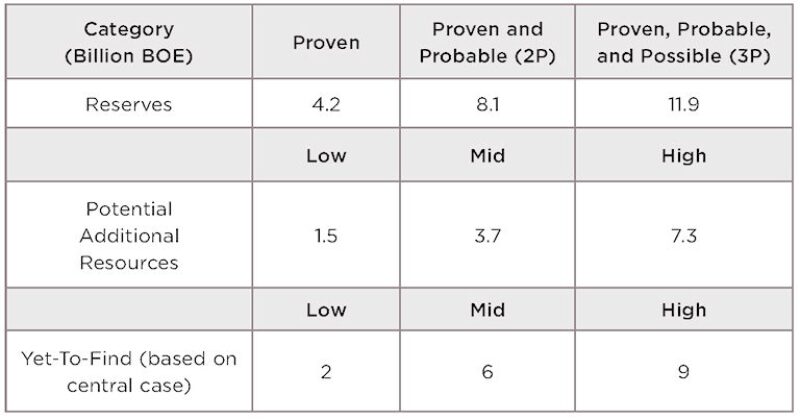

Gains can also come in small increments. Of the oil and gas left in the ground in the North Sea, which is estimated to be up to half of the 43 billion BOE produced since production began, a significant part of it is trapped in small pools.

There are 210 small pools with a total of 1 billion BOE, but the cost of developing pools containing from 3 million BOE to 15 million BOE and connecting them to production platforms is prohibitively high using current methods.

This fall, an OGA committee plans to hold two brainstorming meetings seeking new perspectives on how to unlock those fields from people inside and outside the industry.

Some of these are impossible cases, such as those holding heavy oil that is difficult and costly to produce. Others are now too small to justify the cost of development, but that could change for some if costs were reduced. A 50% reduction could open up the possibility of developing 150 pools, said Matt Nicol, director of nonoperated assets and production for Centrica Energy, who presented the work by a committee on small pool development.

The OGA is also trying to get the industry to think big, with a seismic survey covering 220,000 km2, which is nearly as large as the UK. It looks at two offshore areas where the most recent seismic survey work was done in the 1990s.

The goal of this wide area survey is to attract interest in a 2016 lease sale covering the following frontier areas:

- Rockall Trough in the Outer Hebrides west of Scotland. Since the 1980s, only 12 exploration wells have been drilled in the area, which includes the Benbecula gas field discovered in 2000.

- Mid-North Sea High off the east-central coast of the UK. While exploration in the 1970s and 1980s yielded nothing, new seismic methods will look at deeper formations.

The 2D seismic survey by WesternGeco combines new and old data with modern broadband processing to make the most of low-frequency signals not available in the past. It will be made available next spring for free, in hopes of getting the industry to think more positively about the North Sea.

“Seismic creates confidence, it creates opportunities. We are committed to creating opportunities at the front end,” Seeney said. “It is not confidence for the sake of it. It has to be evidence-based. There are growth opportunities on the UK Continental Shelf.”