Meet Sandy, Nesh, and Ralphie. They are newborn chat bot programs that have been designed specifically to seek out the answers to oil and gas professionals’ tough questions.

These bots, also termed virtual assistants, stem from a branch of artificial intelligence (AI) known as natural language processing (NLP), which has quickly entered the mainstream thanks to the efforts of tech giants Amazon, Apple, and Google.

Their software innovations have enabled many millions of people to engage in dialogue with laptops, smartphones, and speakers. Consumers are using NLP mostly inside their homes for simple requests; music and weather reports round out the top two uses in one recent survey.

But there is now a push to get this technology into the world’s offices where it has the potential to increase worker efficiency. This market test is just barely under way in the oil and gas business where adoption will hinge on a virtual assistant’s ability to quickly generate reliable assessments of complex issues involving reservoirs, seismic data, and well logs.

And like many nascent developments in the digital arena, the technology’s capabilities will also depend on the amount of training it receives from its earliest users.

These first movers are among those vying for the chance to make chat bots an essential part of the upstream sector’s future.

Nesh

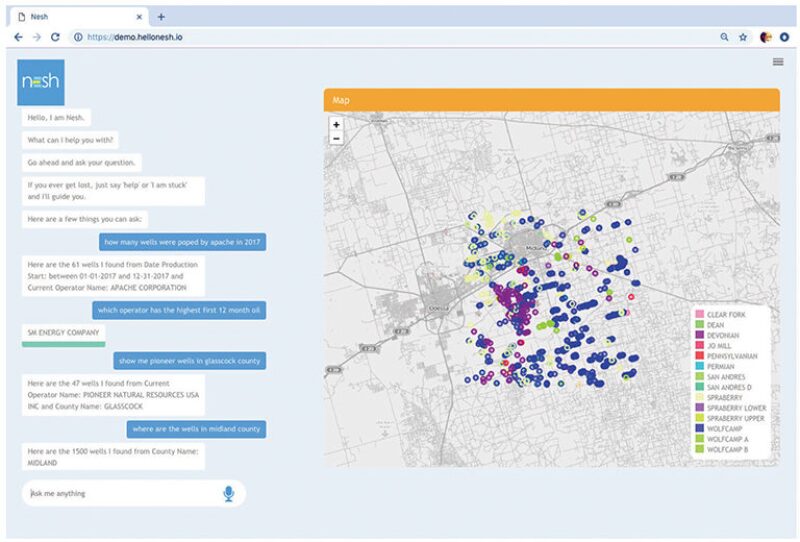

Houston-based startup Nesh has created a virtual assistant by the same name to help industry analysts and engineering techs build intelligence reports. The firm is in the middle of pilot projects with a European operator and one of the largest US shale producers.

Sidd Gupta is the chief executive officer and started the company last year after spending most of his career with Schlumberger, including a stint on one of its software teams. Gupta acknowledged that chat bots have been criticized in the past for being “dumb things” that can only complete a rigid set of pre-programmed steps.

Next-generation chat bots like Nesh aim to reverse this perception with more advanced programming that fetches data for inquisitive users from multiple, usually disconnected, sources.

Gupta drew inspiration for the new venture from a few sources, but one in particular exposed the need for a chat bot technology that could make using complex oil and gas software a more intuitive experience. After a friend was laid off during the recent downturn from his role as a reservoir engineer, Gupta said he was turned down for a job that seemed like a perfect fit, with just one exception: the friend was trained on a different reservoir simulator than what was used by the prospective firm.

“I thought that was a very weird reason to reject someone for a technical role,” he said. “I realized that this was a very systemic issue in the oil and gas industry—we judge people’s technical capabilities based on what software they can use.”

With Nesh, the goal is to remove this learning curve so that anyone—from a CEO to an analyst—can leverage the capabilities of a company’s software programs simply by asking questions. This can be done through speech, or Nesh can be communicated with via the keyboard—likely to be the most common avenue since most office workers will be keen not to announce their every request.

Queries might involve prioritizing infill drilling locations, finding optimal well spacing, or building type curves of other operator’s assets. The latter types of reports are common in the North American upstream sector where companies are constantly analyzing each other for acquisitions and land swaps.

“But we’re also giving insights that you didn’t ask for,” said Gupta, explaining that in the course of putting together a comparative benchmarking report, Nesh might autonomously run a quick modeling exercise to detect nuances such as well-to-well interference patterns. Based on the relevancy of this issue, Nesh could then offer a suggestion to drill a specific section sooner than planned to avoid potential interference with an offset operator’s development plan.

These interactions are made possible by a backend that uses several AI techniques that enable Nesh to interpret the questions and then invoke the right computation to generate an answer. Sourcing the information relies on Nesh being connected to a company’s internal and external data sources, e.g., IHS Markit, a regulator database, or SPE’s OnePetro.

To help its commercial efforts, Nesh has joined an Austin-based accelerator called Capital Factory, which is also the largest venture capital firm in Texas, and a Houston-based accelerator called Eunike Ventures.

Belmont Technology

Belmont Technology is another Houston-based startup developing a chat bot program it calls Sandy. It represents the digital face of the company’s new reservoir modeling software that sits on top of another set of AI programs that interpret seismic data and speed up numerical simulations.

Jean-Marie Laigle, the chief executive officer of Belmont, characterized Sandy as a “shortcut to the traditional workflows” of the industry’s exploration and production process. Early testing has shown that the program can complete some simulations and interpretation tasks 10,000 times faster than the legacy products it intends to compete with.

“When you have a trained, physics-based AI, then you can change your seismic interpretation and have instant updates of the model,” said Laigle, who has more than 15 years of industry background as a geologist and engineer. Some of the things that Sandy is designed to answer quickly include details around faults or the average porosity of a reservoir, which Laigle said is a “simple question to ask, but quite complex to answer.”

In January, BP invested $5 million in the young company to help its upstream unit achieve a 90% reduction in the time its engineers spend on data collection, interpretation, and simulation.

Behind Sandy are a number of programming elements that have been proven for years in the consumer sector. This includes the knowledge-graph technique that is core to Google’s ability to link relevant but unconnected pieces of information together with its search tool. In addition, the startup is creating a suite of intelligent agents to carry out domain-specific tasks with the data. “You can see Sandy as the brain and the agents as its skillsets,” explained Laigle.

One of the other tech firms that Belmont is trying to emulate with its user interface is Slack, the Silicon Valley developer of a popular business collaboration software by the same name. The idea is that by sharing a common interface, the typically isolated exploration disciplines, e.g., geology, geophysics, reservoir, and petrophysics, will be able to see and access all the work each are doing in real-time.

This feature cuts down on emailing and reduces the chances someone will be caught off guard as one group makes an interpretation that affects the entire project team. But it also means that the team is all working on one software platform for the entire interpretation and simulation process—this is a departure from the piecemeal process that has historically involved handing off the results of several software to people who may not have them installed.

Last year, Belmont was recognized for its technology’s potential in startup competitions held at the 2018 Offshore Technology Conference and the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition. The company is currently running proof-of-concept projects with operators and expects to reach commercial mode by the end of 2019.

Earth Index

Earth Index is another pre-commercial startup from Denver that has joined the fray with its chat bot Ralphie—named after the founder’s father who helped build a framework of US well and log data that can be used to investigate a reservoir’s target zones.

Danielle Leighton, the chief executive officer of Earth Index, launched the firm to take advantage of that geologic data which she and her father, Ralph Williams, put together over a 20-year period while leading another business. She explained that the business goal is “to bring instant context to any oil and gas investment opportunity” by combining the basin-wide geologic data with public production figures.

Ralphie will allow users to search for prospective acreage or formations of interest and generate visualizations or written reports of how they are producing. The frontend of Ralphie, like the other chat bots in this space, is powered by a backend AI engine that parses through geologic and economic information.

“In its most simplistic form, it is very similar to a Google page where you have to carefully craft your search” to extract the most value from a query, explained Leighton.

One of those components is the same AI program used by the US Geological Survey’s earthquake information center to locate tremblors in real time. Earth Index has obtained the exclusive license to use the software in the oil and gas industry where it will find and cleanse data before serving it up to users.

There is a lot of competition in the reservoir evaluation space, most of which Leighton said comes from oil and gas company in-house teams. “The chat bot is actually the biggest way that we’re trying to distinguish ourselves,” she shared, adding that she thinks the technology will attract business by helping to remove egos and the ad hoc nature of the oil industry’s deal making process.

“It’s not just one geologist telling another geologist that they have this data set, and that it might possibly be better than what they have,” she said. “The computer is taking the data approach—so there is no personality involved. If it’s not in the data, then it doesn’t give you an answer.”

Earth Index is still developing Ralphie and expects to have a prototype for operators and venture groups to begin testing soon.