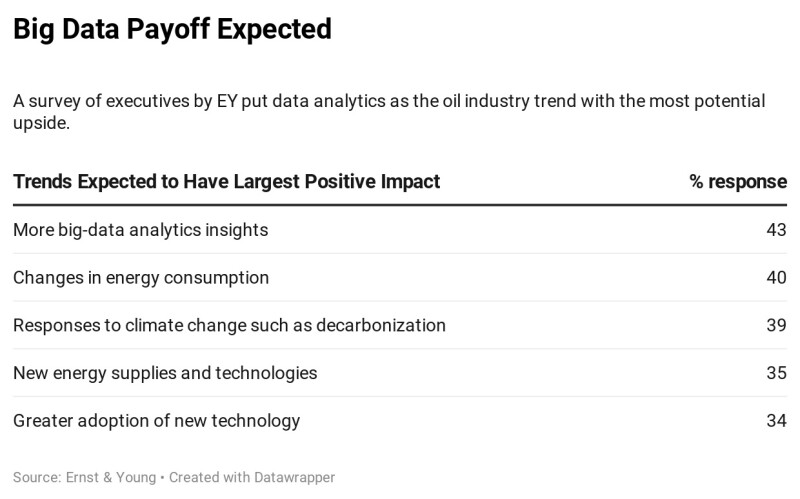

Oil industry executives surveyed last year ranked the potential positive impact of big data analytics at the top of the list of trends, higher than even changes in oil demand.

That bold conclusion was from a survey by accounting firm Ernst and Young (EY), putting big data analytics among the top trends that could aid business growth in the next 3 years, even above the demand swings that move oil prices.

The survey may have reflected the mood last summer when the outlook for oil consumption looked so weak that cost saving was the only path to better results.

“The survey speaks to a high-level ambition across the operator community to use digital as a mechanism to drive down costs,” said Toby Summers executive director for EY. The promise there is that digital can allow them to scale up operations with fewer hires in good times and scale back with fewer layoffs when the cycle turns down.

These projects also cost less than other cost-cutting options.

“Digitization is one of the cheapest ways to get the business more resilient,” said Patrick von Pattay, a vice president for Wintershall Dea, a Germany-based independent, and chairman of the Digital Transformation Committee of SPE’s Digital Energy Technical Section.

Process changes supported by digital analysis can cost a couple hundred thousand dollars; that is not a lot of money in a business where a single offshore well often costs hundreds of millions.

What is not obvious is who does the work.

The rush to digital has scrambled traditional relationships with oilfield service companies and brought in new players, from Silicon Valley giants to a flurry of startups in the oil business, a few of which have become established players.

As a result of the change in the technology, and the business models of the upstarts, oil company technical teams can and do play a more active role in digital technology development and use than in the past.

Changes began in 2014, when the sudden end of $100/bbl oil forced oil companies to drop their long-time reliance on owning their own computer systems. Oil companies finally joined the decade-old shift to buying data storage and processing as a service from giants such as Amazon and Google. That facilitated digital innovations by centralizing their data, eliminating splintered storage systems that hindered analysis.

The giant looming over the service business now is Amazon Web Services (AWS). The cloud storage arm of the online retail and logistics giant has grown exponentially, doing everything from selling an array of digital tools to promoting a list of preferred energy providers.

Digital newcomers disrupted relations with service companies that had built software solutions and sold equipment programmed using proprietary coding.

Increasingly user-friendly tools for visualizing and analyzing data, plus the ability for smaller companies to buy data capacity, allowed engineers to do more and allowed midsized companies to act like big ones.

“There has been a shift now; the independents have access to the same tech as the big guys,” Summers said.

Those big players, as well as smaller names from the tech and oil sectors, eagerly courted oil companies, selling things based on widely used software languages such as Python.

“What we get from young fresh companies with a great vision, with a great drive to deliver, they are giving us the opportunity to grow beyond the classic service companies,” von Pattay said.

Having a Say

A big difference in these newcomers is that they offer a palate of tools for problem solving rather than selling solutions, von Pattay said. Those tools offer users a greater measure of control over diagnosing and treating problems.

From the time that desktop computers started appearing on engineer’s desks in the 1980s, companies sold reservoir modeling programs and performed seismic interpretations.

Now equipped with tools that allow them to do more, technical teams can insist on having a say in the digital methods used for interpretations that play a critical role in determining exploration and development success.

“Five years ago, oil companies sent seismic data off to service companies for interpretation. Now, they are working with third parties to create special capabilities that allow them to do that on their own,” Summers said.

Third-party experts in the drilling and completions sector, from the giants to smaller competitors such as Corva and Well Data Labs, are jockeying to establish a competitive advantage in a sector where the battle to survive can be Darwinian.

Some breathless product announcements make it sound like oil company engineers can do it all themselves. A release from Lloyd’s Register said its low-code asset-optimization program “removes the cost of outsourced technical expertise.”

There is some truth to the hype. Savvy engineers are capable of doing more with applications from companies such as C3.ai and Tibco, which makes Spotfire, a sort of Excel for the big-database age plus artificial intelligence add-ons.

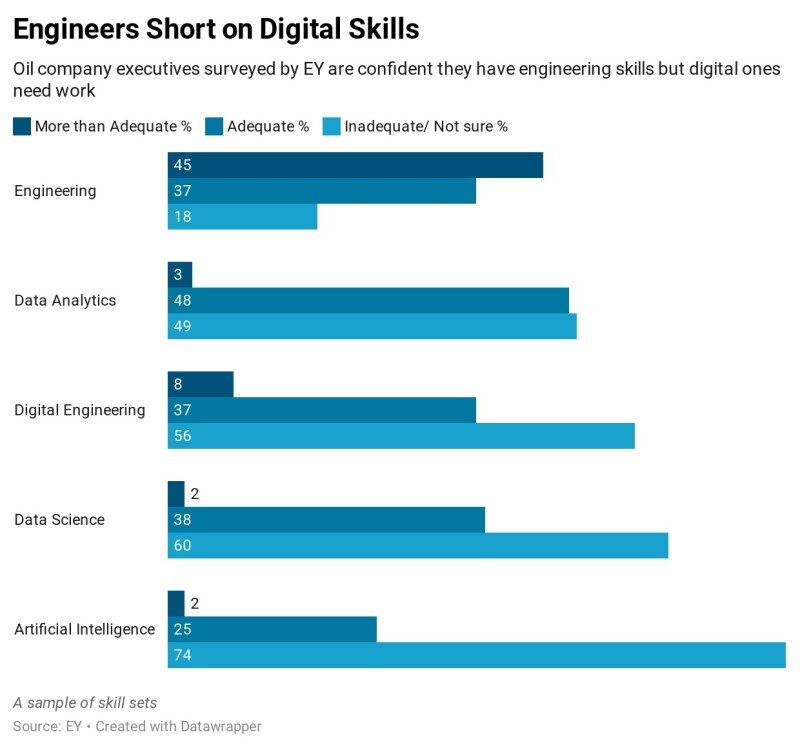

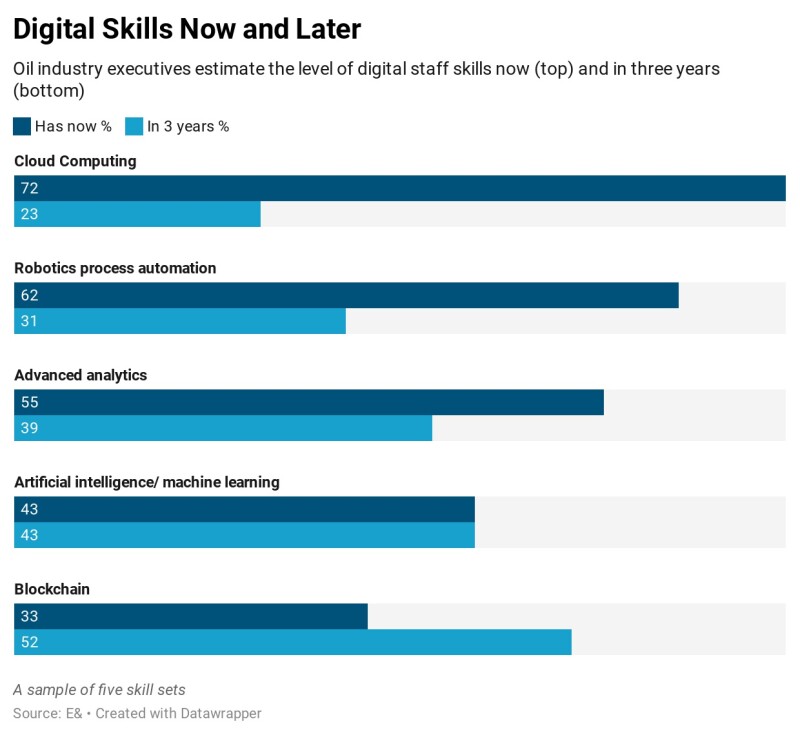

But those executives who put digital at the top of the list also told EY that their in-house skills fall well short of the expected need in critical areas such as artificial intelligence.

Since then, those human resources have shrunk with mass layoffs in some of the biggest oil companies and mergers in large US independents designed to increase profits by allowing fewer staff members to manage more acreage.

Operators are looking to third-party suppliers for ideas and analysis to support efforts by staff members focused on problems with the greatest effect on production and the bottom line.

Neptune Energy has an adviser ecosystem. Those invited have access to meetings where they share “challenges we have and the opportunities” for partners, said Kaveh Pourteymour, chief information officer for the London-based independent.

Those in the ecosystem benefit from a symbiotic relationship, like sharks offering protection and food for pilot fish that aid the shark by eating irritating parasites, some of which are found in the sharks mouth, where the pilot fish safely feed on scraps of meat stuck between teeth.

An ecosystem also makes problem-solving easier by ensuring the third-party providers are already familiar with a company’s people and its way of doing things, said Meindert Dillen, a member of the digital team at Wintershall Dea.

“We’re much more about a collaborative effort with partners/vendors to create platforms and tech rather than relying on others to do it for us,” said Gavin Roberts, head of communications for Neptune.

Digital People Development

Companies form ecosystems that allow them to direct the process, but the result often comes from the outside.

“Whether you buy it or develop it … take the best solution,” Dillen said.

Defining what is best requires building a technical staff able to identify ways to improve performance and the digital steps they could take that will help address them.

That human element is critical because digital analysis of what goes on in a well is fundamentally different than analyzing retail sales data.

Skilled people are needed because petroleum engineering requires interpreting data from a narrow tunnel deep in the ground. The errors in a sales report are small compared with the possible mistakes based on data from a well where sensors often fail, the point of measurement is often far from the point of interest, and the data is often not a direct measure of the property estimated.

The mix of skills needed for a digital engineer, according to von Pattay include the ability to code, to break down a complex problem logically and translate the problem out of domain knowledge into the mathematics of modern digital solutions.

Humans able to do all those things are rare, so staff members at Wintershall Dea created a cooperative network of 100 to 200 technical staff members to help people with a wide range of backgrounds to combine their digital and engineering skills.

The program assumes that challenging technical staff members to solve critical problems facing the business will motivate them, and, the company hopes, that will help the company retain top talent.

Wintershall Dea’s results over the past 3 years have included things that were ahead of the curve, but Dillen said they need to keep looking to do better.

“We don’t know what will be available next year, and we want to be ready for the next technology. We want to have the capability to apply it,” Dillen said.

Getting Easier

The independent companies that pioneered the shale oil business by mass producing wells were a natural proving ground for new digital providers.

Corva grew rapidly to as high as 300 rigs before sinking with the rig count last year. Its strength was its ability to create networks of screens displaying real-time drilling information, and later fracturing data, in the field and in the office. The clients ultimately included ExxonMobil, which used it to support its aggressive Permian drilling program and has since added the screens to offshore rigs as well.

Data Gumbo demonstrated to an industry consortium how it could automate the process of tracking wastewater shipments to disposal wells, using the real-time data gathered to generate an invoice and payment. The process can be applied to a wide range of goods and services.

Well Data Labs, which started out cleaning up fracturing data so it could be processed, has built a staff of approximately 40 data and fracturing experts to steadily upgrade its fracturing analysis tools.

Small data service firms, along with everyone else in the shale business, had a rough ride in 2020. But they all expanded what they do and are still talking tough.

“In the future, there will be a lot of smaller companies; they will be different from the companies you traditionally bought from,” said Ryan Dawson, founder and chief executive officer of Corva. The “ideas that will drive down the cost of wells will not come from Schlumberger and Halliburton.”

Those big names would say otherwise and have been making changes to back that up.

“I feel like service companies are adapting well under as much or more pressure as anyone else,” Summers said. He added they “have been forced to reconcile what they do well … to focus on solutions that help the operators through this.”

All of them are jockeying for the insider access needed to know and help solve the problems that operating companies have decided to address.

“You do need to get embedded into the fabric of the industry,” said Andrew Bruce, CEO of Data Gumbo, whose business has created a network of oilfield buyers and sellers who use its paperless, automated logistics payment system built on blockchain, with rules laid out by smart contracts, agreements that define the workings of a digital system.

The thinking behind his business model is that it offers a check to the potential barriers to entry for those selling services to oil companies—from data access to solving problems—where the financial payoff is not obvious to an accountant.

Well Data Labs’ history can be tracked based on its increasingly sophisticated use of technology. It began with cleaning data and, over time, developed ways to label each stage and determine when pumps turned on and off. This step-by-step process has made it possible for it to attack problems directly related to fracturing efficiency, such as looking for pressure signals that indicate casing damage.

Unlike pilot fish, whose place in the ecosystem is based on surviving the same problem over and over, oil data services providers need to keep finding new ways to change how customers work.

“It is about change management. Software has no value without change and a transition of the culture around process. Without those things, backed from the top down, a digital effort will not work, period,” said Joshua Churlik, chief executive officer for Well Data Labs.

Who Does What?

In the oil business, sometimes the shark bites.

An example came from a video of a presentation by a digitally savvy drilling engineer with a US independent explaining how he used easily available tools to clean up fracturing data.

The online presentation was part of an online offering from Tibco, the maker of Spotfire—a program used to analyze and visualize massive spreadsheets—which was one of the tools he used to turn raw spreadsheets from a fracturing site into data that can be easily digested by computers for analysis.

It covered work done last spring, when drilling was on hold because of the oil glut. The work took 6 weeks, using tools available on AWS plus Spotfire. He said it cost less than $1,000 to set up and run—a tiny fraction of the annual cost of having the work done by a third party. He was looking forward to a chance to field test the program developed using historical data.

The engineer in the video could not get permission to answer questions about the presentation, which had become a point of contention between his employer and the third-party provider, Well Data Labs.

It offers a case study of this big, messy transition in progress where companies with digital needs must decide what capabilities they should build in house and when they should pay others to do it.

While the money saved by building a data-cleaning solution looked big to any normal person, it would not be a lot for an oil company that would be spending millions per well on fracturing.

The cost estimate in the video did not include the value of 6 weeks of an engineer’s time. A rough estimate based on the SPE salary survey would be approximately $20,000 for an experienced engineer. It also did not offer a guess of what an engineer could have accomplished if the time were spent on a project directly related to more effective fracturing.

Churlik declined to comment on a problem resolved with a customer. But he recognizes his business’s future can be altered by oil company decisions on what to buy and what to build.

Other programmers have created systems to clean up fracture data, some of which led to startups to sell the service. It is not that hard to create a program to clean up the data from a single well generated over a few days. It gets considerably harder when the program is used on many wells with many differences in labeling and formatting that are predictably unpredictable.

“For the most part, these applications are at a prototype level. They will not stand up to scaling up to 200 wells with four or five service companies,” which can mean differences from shift to shift, Churlik said.

Data cleaning helped Well Data Labs build up a customer base and revenue, making it a platform—a vaguely defined label for a company that customers depend on based on its unique strengths.

To maintain that status, Well Data Labs is looking for new services that customers value that will be hard to replicate. Fracturing data cleanup is a difficult problem to solve, but low-cost competition is inevitable, so Well Data Labs’ staff is regularly adding new services for customers.

“The ones that are going to survive are the ones that will continue to innovate,” Summers said.

Last year, Well Data Labs presented the first of a series of papers on its search for ways to use fracturing pressure data to detect events during fracturing, such as casing damage. That project grew out of a collaboration with Chesapeake Energy and has since incorporated input from other operators.

It has also begun selling a service that allows users to use a process developed by Devon Energy to measure pressure changes in wells during fracturing using data gathered in a sealed wellbore nearby.

A common theme in its work is using its expertise to allow a machine to objectively identify patterns in massive databases, a theme it had identified while working closely with oil company engineers.

“We collect so much data. It’s not that users are not looking at it … they just don’t have the time to examine closely four or five wells in a pad with 50 or 60 stages each,” said Jessica Iriarte, research manager for Well Data Labs.

Code Assembly Required

During the past year, Corva has become a competitor in the fracturing analysis business, with a real-time monitoring service and a growing list of applications.

The company has always played up the value of its applications, emphasizing the quality of its displays, which its customers can select to display on its screens

For ExxonMobil, that view included its own programs. What drew it to Corva was its ability to quickly create a network of screens that provide a common view of drilling on all the rigs it leased as well as on the laptops of its engineers.

“We could run it for one rig on a laptop, but there is no easy way to push it out to the rest of the fleet at one time,” said Brad Barton, the wells digital and automation manager at ExxonMobil.

The major requires drilling contractors to use its proprietary code because, he said, “IP ownership is important to use as a differentiator.”

Barton spoke at a Corva webinar last August, where it rolled out its new offerings that are designed to make it easier for its users to build their own applications in its development center and sell or share them if they wish in its app store.

Dawson said several large oil companies are interested in finding a way for their engineers to turn their ideas into applications.

The process of creating a program has gotten easier for those familiar with where to look for useful bits of code and ready-made tools found in online hubs that are cut and pasted together with a minimum of code writing.

Corva has code to offer and expertise on problems to address scaling up programs, from making sure they do not harbor bugs or viruses to limiting who has access.

Creating and supporting software for users will remain a priority. Companies have some ideas they want to turn into apps, but there is a limit. Dawson said even ExxonMobil has more suggestions than Corva can handle for software improvements in areas that it does not consider proprietary.

Dawson has ideas as well. He would like to see someone use vibration data gathered during drilling and create an application showing how the actual vibration during drilling compares to the limits set by manufacturers.

Application creation can also be a way for service companies to connect with customers on screens by making them more aware of how specific products perform downhole. The challenge will be finding data that is sufficiently useful to be chosen on these crowded displays.

And Dawson said someday the app store might provide a market for “two guys in a garage in Houston who probably have some amazing ideas.”