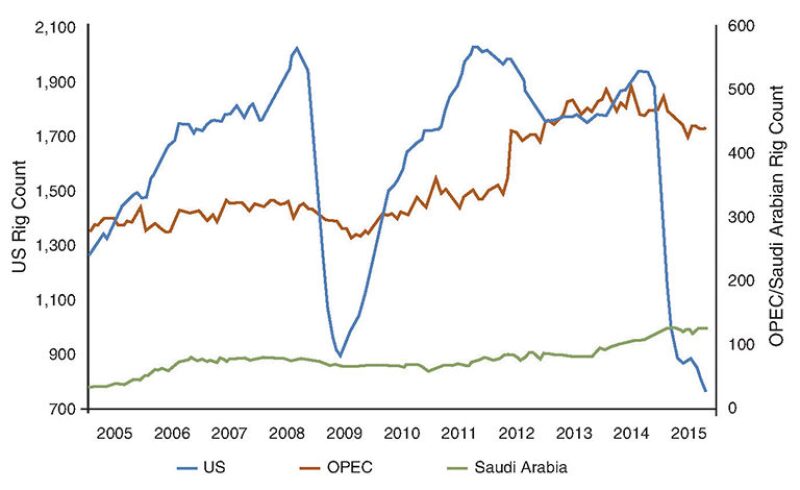

Plunging oil prices led to a drastic drop in drilling rigs working in most places in the world, with a notable exception. Baker Hughes’ widely watched weekly report on drilling rigs shows activity has remained steady in Saudi Arabia and the Middle East.

Those countries possess rich conventional, onshore oil reserves, where the cost of lifting a barrel is still solidly profitable at prices below USD 20/bbl. These countries have millions of barrels a day of capacity and plan to produce it.

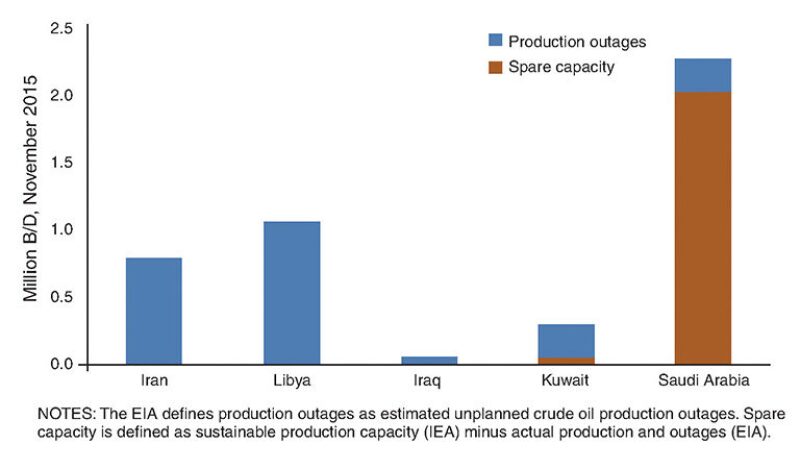

Iran has said it plans to export 500,000 BOPD of oil as soon as it is allowed back in the market, which depends on its compliance with an agreement to dismantle its nuclear program.

Libya’s warring parties recently announced a fragile truce with a goal of forming a national government, which might allow it to increase exports that could rise to 1 million B/D this year, according to Nouri Berouin, chairman of the Libyan national oil company. The comment was in a report from the Middle East Policy Council that said the company is working to ramp up its output from 350,000 B/D to 600,000 B/D.

Despite conflicts in Iraq, Iraqi production reached 4.5 million B/D in November. It has added more than 1 million B/D of production over the past 12 months, nearly twice the added output of Saudi Arabia, according to the US Energy Information Administration. Iraq plans to continue increasing production, and Saudi Arabia has about 2 million B/D of spare capacity if there is a need for it.

Even the United States is exporting crude oil again, with a law taking effect early this year eliminating a long-standing ban.

One indicator of the changing geography in oil production is the disappearance of the spread between the value of the US benchmark crude, West Texas Intermediate (WTI), and the international standard, Brent crude.

When US oil production was growing, the US export ban led to an oversupply of high-quality crude that depressed WTI prices. Not long ago WTI tracked for USD 10/bbl less than Brent. Now that supply is growing internationally, there were days in December where Brent sold for a bit less than WTI.

Another sign of the shift is that working rigs drilling in North America now represent less than half of the rigs working in the world, falling from 60% at the end of 2014 to less than 43% at the end of 2015, according to the Baker Hughes weekly rig count.

Saudi Arabia has established that it is once again the dominant force in the world oil markets, and it is planning for lingering low prices. Its 2016 budget reduces its sizeable deficit by cutting subsidies for everything from energy to water, and it assumes an average Brent oil price at USD 37/bbl in 2016, according to John Sfakianakis, a Riyadh-based economist at Ashmore Group, the Bloomberg news agency reported.

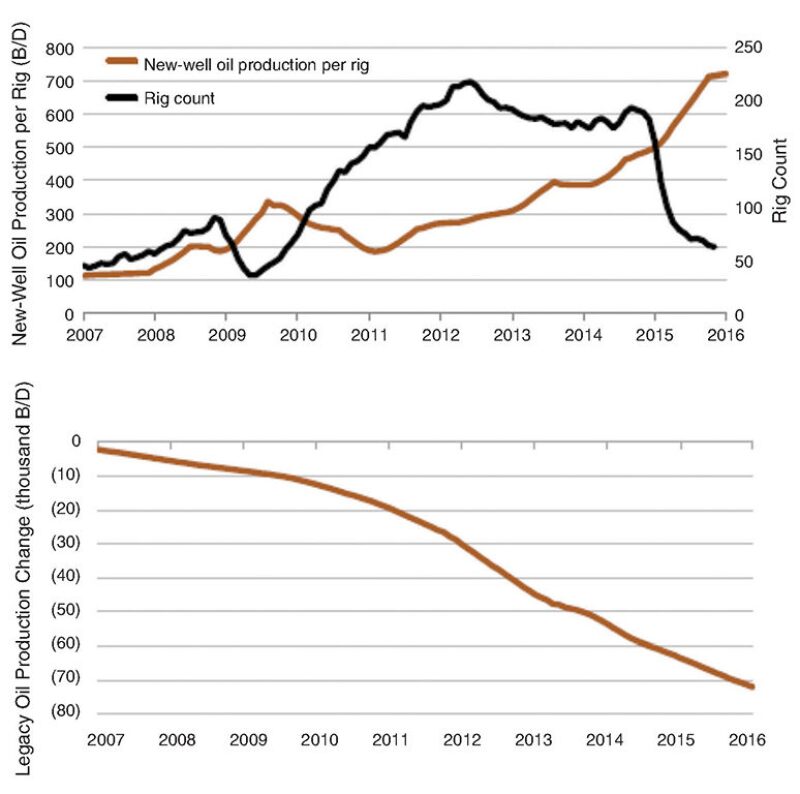

Prices that low will speed the decline of US unconventional oil production, which was only marginally profitable at around USD 50/bbl. Before the price decline, US producers were producing more oil per well drilled, but on the downside were the number of rigs working (down more than 60%) and the production decline rate in older wells.

For example, in the Bakken, there was a 40% average increase in the output of new wells, but a more than 60% drop in the number of new wells drilled to fill the gap left in output as older wells’ production declined. An EIA chart did not suggest any improvement in that rate.

Being the low-cost leader is a role change for Saudi Arabia, which long was willing to reduce supplies to sustain prices. But when US production surged and demand growth from China slowed, it shifted to defending its share of the market.

The current situation is similar to other commodity markets, such as the corn market. When prices go down, farmers commonly grow more to try to maintain their income. While the richest oil producers have a big price edge when it comes to lifting crude, national oil company profits are needed to pay for everything from energy and education to defense and desalination plants.

As prices drop, more production is required to pay for these politically vital programs, which can sustain an oversupply that depresses prices.

“There are a lot of similarities” with farm commodities, said Karr Ingham, a consulting economist for the Texas Alliance of Energy Producers. “They are all commodity markets for one thing. The market structures are much the same for agricultural commodities as petroleum commodities. The biggest producer in the world has little to say about what the price is,” which is set by the markets.