In January of 1949, a new publication jostled for its place amidst the sudden abundance of titles devoted to technical professional associations. The publishing marketplace, like every other, was evolving daily in a world that hoped technological leaps never before imagined would not only leave behind recent global tragedy but also make its recurrence impossible.

Volume 1, Number 1 of the Journal of Petroleum Technology—then the official publication of the Petroleum Branch of the AIME—wore an efficient but striking clover-green-and-cream cover, its 92 pages containing sections devoted to editorials, AIME-wide developments, upcoming meetings, feature articles, and technical papers (including, famously, a paper on a new technique that author J.B. Clark dubbed “Hydrafrac”).

The teaser text for Branch Chair I.W. Alcorn’s inaugural Editorial Comment framed the new magazine as “the kingpin of a broadened branch program and a real force in strengthening the profession if members will but use it to carry opinion and incite action.”

As JPT celebrates its 75th anniversary, a brief review of the global petroleum landscape during its first year of publication casts new light on the magazine itself—and the lofty expectations attached to the industry it supported.

Europe: The Wall and the Well

Before a rebuilt world could be fueled by petroleum, the conditions of its peace had to be defined, and thus its eyes were on Europe in 1949. The Marshall Plan had enabled a major uptick in European oil production, such that Western Europe produced just over 11 million bbl in 1949 in countries such as the Netherlands, France, and the just-established Federal Republic of Germany.

More than a decade distant were offshore discoveries that would revolutionize Europe’s role in global petroleum, but at the time of JPT’s launch, Europe remained a potential trigger for a war that all were desperate to avoid—indeed, in the UK, wartime rationing had not yet ended, and in the year of JPT’s debut, the petrol ration was increased to allow a generous 180 miles per month.

While the globe remained in upheaval as anticolonial rebellions were launched—mostly against European empires—and attempts were made to fill power vacuums, the showdown between the West and the Soviet Bloc had solidified into a dangerous reality that cast a shadow over every nation. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization was ratified in April, and the following month, the blockade of Berlin came to an end in what was seen as a major symbolic victory for the West, evident proof that its reliance upon technology could safeguard humanity.

The Middle East: Awakening Giant

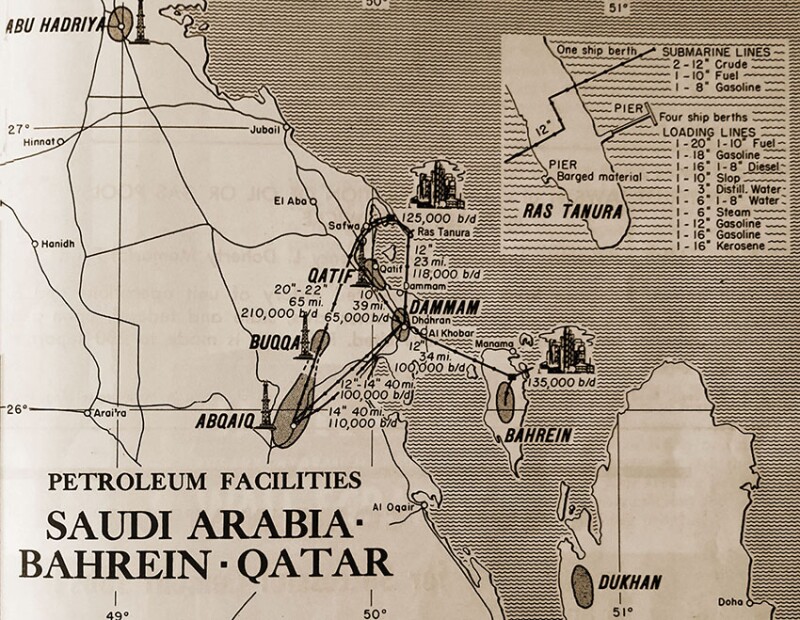

JPT wasted no time, however, in drawing attention to another part of the world that had already been positioned as the industry’s next focal point. The January issue featured the article “Middle Eastern Oil and Its Importance to the World” by Standard Oil’s John R. Suman, in which the author described the inevitability of the region’s economic ascendancy as the result of its oil reserves (35 billion bbl at the time of the article’s writing). While avoiding specific discussion of the political strife that the region had already experienced since the end of the war, Suman, like so many other analysts of the time, explicitly connected its powerhouse potential to the dream of a stable future: “The present program for European recovery makes it (the Middle East) the key to avoidance of another early war. I don't know of anything that could be much more important than that.”

Petroleum development was seen not merely as a key to prosperity, but to peace itself. Recognizing that petroleum infrastructure and production would be vital to the success of the Marshall Plan, Suman and his colleagues understood that the oil-producing nations of the Middle East would soon be “transforming an area of great and almost universal want into one of general prosperity and comfort.”

Indeed, the period was transformative for the Middle East; the very next year, its crude petroleum exports would increase by almost 50%, and it would surpass the Caribbean as the world’s largest crude-exporting region. While most activity at the time was centered in Iran, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia, E&P efforts would soon lead to gigantic leaps in production in neighboring nations as well.

Central Asia: Caspian Crude

Such growth was not, of course, only occurring in areas politically or economically dominated by the West. Behind the Iron Curtain, the coast of the Caspian Sea had long been an important source of oil for the Soviet Union, whose Azerbaijani republic produced 75% of the country’s oil during the war and which had been the target of a failed German offensive to starve the Red Army of its fuel.

But in November of 1949—the same month that JPT published a column by AIME President L.E. Young cautioning vigilance against the infiltrations of socialism even as the organization reaffirmed its official policy of nonparticipation in all things political—Soviet engineers operating from a shed atop a small Caspian island struck oil 1000 m under the seabed. The discovery, soon named Oil Rocks, would lead to the world’s first offshore oil platform and an infrastructural investment that would bloom at its peak into a network of 2,000 drilling platforms, an otherworldly floating city the Soviets long upheld as a technological feat to rival anything constructed by the West.

Asia Pacific: The Perils of Rebuilding

In the Pacific Rim, petroleum production had begun to regain strength after the cataclysm of Imperial Japan’s expansion and defeat; by mid-1950, 195,000 B/D would be produced in the region, an amount that may seem extremely modest until one considers the violence that had scorched its islands and mountains for much longer than the official duration of World War II. The importance of petroleum to the economic and social development of East Asia had long been recognized, and in fact much of Japan’s wartime strategy had been motivated by its need to secure petroleum resources in the Dutch-held East Indies.

The geopolitical vacuum left by Japan’s surrender was quickly filled by the Allies; in what would become South Korea, for example, a trio of American oil companies reached agreements with the new nation’s US-backed government in 1949 intended to stabilize its future and guarantee American influence. That influence, and the creation of a new American ally, was to be secured at a terrible price only months later.

Oil was certainly not a primary cause of the Korean War, but the zeal to create a global economic network locked into industrialization, and the petroleum that powered it, mirrored the geopolitical course of the Cold War. Throughout Asia, as elsewhere, populations long under the domain of colonizers and invaders saw the end of the war as a moment of long-sought freedom but did not always anticipate that these freedoms might be delayed, and indeed sometimes opposed, by a new order that saw technology as the most-important agent of personal liberty.

Africa: Peace Brings Struggle

The colonial quest for Africa’s resources and land may have been centuries old, but the acceleration of that quest into the historical “Scramble” at the close of the 19th century was hardly ancient history in 1949. With the end of the world war, these colonial empires faced growing pressures they could not withstand. African troops had fought with distinction on every front of the war in the Allied cause of freedom, and many, upon their return or demobilization, saw the resumption of colonial dependence in peacetime as an impossibility.

At the time of JPT’s debut, Egypt, a kingdom that remained firmly in the sphere of British influence, was responsible for 99% of the 16 million bbl of African oil produced that year. In terms of the new petroleum-centric world, Africa was seen primarily as the neighbor of the Middle East’s abundant fields—but that would change dramatically in the next decade, when vast discoveries in Algeria, Angola, Libya, Nigeria, and elsewhere would transform the continent and its role on the international stage. As oil was discovered and produced in massive amounts, nascent independence movements discovered new leverage, and Africa quickly became arguably the most inflamed of Cold War battlefields.

Latin America: Advancements and Alternatives

Latin America was central to the world oil scene at the time of JPT’s launch, mostly because of its star performer Venezuela. The nation was the world’s second-largest producer of oil that year at nearly 1.6 million bbl, and the world’s largest exporter of crude.

A brief period of democracy had ended the previous year, and the new military government was determined to take firmer hold of the national oil industry and its profits. It thus extended a fateful invitation in 1949 to four other major oil-producing nations—Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia—to consider formation of a body that would represent the interest of oil producers as a counterbalance to the US and its corporate “Seven Sisters” that dominated the world’s oil industry.

While the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries would not be chartered officially until 1960, it would not be long before the effect of Venezuela’s initiative would be felt globally. In the meantime, Colombia, Argentina, Trinidad, and Peru were building their own industries throughout 1949, with Colombia in particular, despite struggling through a bitter civil conflict that had erupted the previous year, showing great promise for the future.

North America: New Directions, New Resources

Unsurprisingly, JPT’s focus during its first year was on North America. The magazine’s content was, then as now, member-centric, and most members were in the US; thus, its pages brought readers news of the establishment of the new Petroleum Division of AIME, branch activities and growth, spirited exchanges about the desirability—or lack thereof—of engineering specialization within the industry, and technical programs for upcoming meetings in San Francisco, California, and San Antonio, Texas.

But momentous industrywide events also were unfolding in North America. The Spraberry Trend had begun to produce, heralding a shift to the Permian Basin in domestic production that would endure until the offshore boom.

And in that domain, 1949 saw a critical technological development as the Breton Rig 20, the first offshore (specifically, out of sight of land) drilling rig, began operations in the Breton Sound of the Gulf of Mexico (GOM). More than 40 wells were producing in the GOM by year’s end. Mexico itself, long a top world producer, made agreements with US drilling contractors in March to handle operations for the first time since the nationalization of its oil industry a decade earlier. Finally, the December issue of JPT featured an article by Imperial Oil’s J.C. Gustafson highlighting the fact that 45 rigs were then active in the increasingly important Devonian pools of Alberta, Canada.

Conclusion: Peace, Progress, and Petroleum

In the wake of World War II, the industrialized nations of the world, riding the momentum of technological accomplishment and cooperation that had destroyed the Axis, took it as their right to organize the globe’s recovery and label its identity. Often failing to consider the realities and desires of the hundreds of millions of people affected by their policies, they believed that an optimistic embrace of technology would prevent a recurrence of what had just been endured. Viewed the better part of a century later, such optimism can present an easy target: quaint if not naïve, the result of an all-encompassing consumerism bursting forth from a resurgent US and, as told in the West at any rate, sweeping all before it.

But one can hardly begrudge optimism, whatever its strain, in a global population emerging from the darkest years in recorded human history. Certainly in our own time, we, too, doggedly link technological progress with the betterment of human civilization—and, just as in 1949, hope that prosperity brings peace.

Crediting the debut of JPT to these impulses may seem grandiose, but it is clear enough from a review of the magazine’s first year, and the industry to which it was devoted, that its creation was born of more than merely a committee vote. It was, in fact, an attempt to chronicle an unmistakably new era.

For Further Reading

Petroleum Developments in Europe in 1949 by F.E. Von Estorff, AAPG Bulletin (1950).

Summary of Recent Economic Developments in the Middle East United Nations World Economic Report (1952).

Forbidden City of Oil Platforms: The Rise and Fall of Stalin’s Atlantis by Arno Frank, Der Spiegel (2012).

Petroleum Developments in Far East in 1949 by F. Barnwell George, AAPG Bulletin (1950).

The Secret of September: The 1949 Oil Agreements Between the United States and South Korea by Ohsoo Kwan, Modern Asian Studies (2023).

Petroleum Developments in Africa in 1949 by Hollis D. Hedberg, AAPG Bulletin (1950).

Petroleum Developments in South America and Trinidad in 1949 by Merrill W. Haas, AAPG Bulletin (1950).

US Group to Drill for Oil in Mexico, The New York Times (1949).

The World’s Nuclear Nation Assesses Petroleum Vulnerability

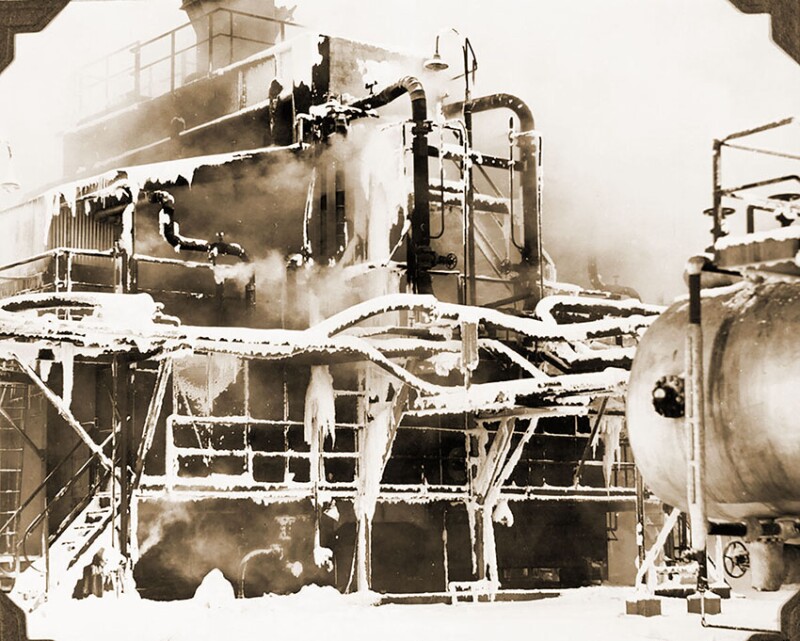

Every adult human would, in 1949, have been familiar with the notion of technology’s destructive potential. While petroleum had powered the Allied drive to victory, developments in aeronautics, metallurgy, chemistry, and a host of other sciences also had proved critical. The most universally identifiable of these, of course, was the creation of the atomic bomb.

When JPT’s first issue shipped, the “nuclear club” still counted a membership of one, but that member harbored no illusions about the inevitability of proliferation.

In Commander Robert C. Wing’s paper “Potentialities of Atomic Warfare Against the U.S. Petroleum Industry,” published in the September 1949 issue of the Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute, the positivist view of these devastating weapons that can seem so alien to modern sensibilities is evident but is tempered with the acknowledgment that the US’s all-important petroleum industry appeared deeply vulnerable.

“When war comes, and if with it comes the atomic bomb,” Wing wrote, “the refinery industry because of its concentrated nature will be in an unenviable status if it is selected as a high-priority target objective.” Despite the infrastructure’s potentially “unenviable status,” however, Wing predicted that US ports, because of their sheer size, would be able to endure a nuclear attack and continue their important functions. “It is unlikely that atomic bomb production can achieve, at least in our time, anything like mass production.”

Here, one sees an optimism that seems now at odds with the science it supports. But, as always, context remains critical, and in 1949, nuclear deterrence was viewed by many as a guarantor of peace rather than as a constant existential threat.

In any case, the apprehension of Wing, and others who foresaw the spread of nuclear weapons, was well-placed. On 29 August, likely only weeks after Wing had finished writing his paper, and a full 3 years earlier than American and British analysts had anticipated its ability to do so, the Soviet Union successfully tested its 21-kiloton bomb “First Lightning” in what is now Kazakhstan. The “club” was exclusive no more.

For Further Reading

Potentialities of Atomic Warfare Against the U.S. Petroleum Industry by Robert C. Wing, USN, Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute (September 1949).