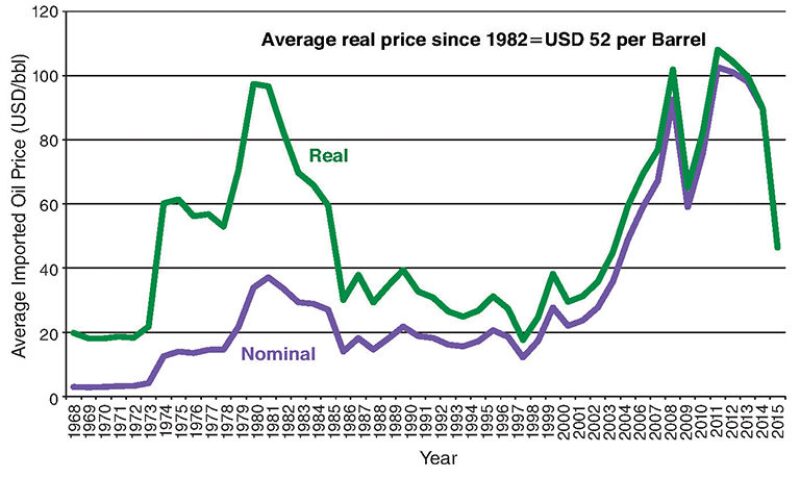

Since 1982, the year oil prices were deregulated in the US, the import oil price to the US has averaged USD 52/bbl in 2015 dollars. It is volatile, having a monthly standard deviation of 9%, although volatility ebbs and flows. The global oil price, like the price of any commodity or security in a free and open market, incorporates all available information almost instantaneously and follows a random walk pattern.

With the above factors in mind, what can today’s oil and gas professional expect for the near- to mid-term oil price? Although the answer may not be welcome, a fairly stable set of conditions coalesce to make a strong reason to expect the oil price to generally range between USD 30/bbl and USD 60/bbl for the foreseeable future.

The Global Macro Situation

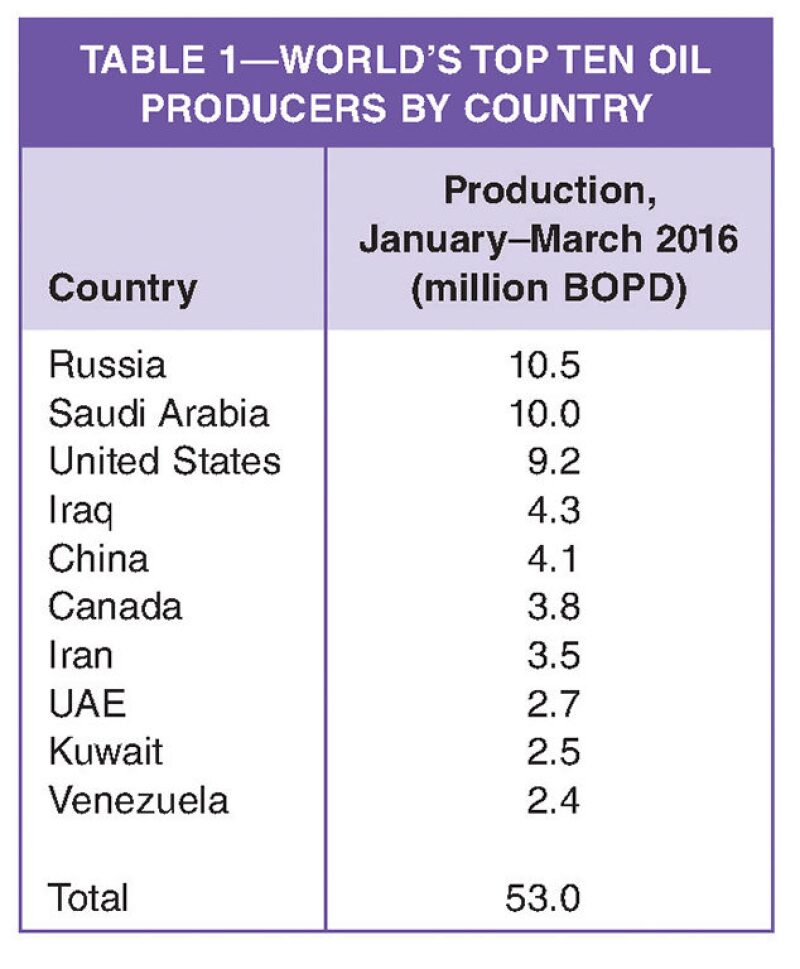

To understand the situation, it is helpful to first look at two global macro factors. First, the world consumes approximately 90 million bbl of oil every day. And second, three countries, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the US, are the largest suppliers, with each producing between 9 and 11 million BOPD (Table 1). Beyond these three countries, production drops precipitously.

The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) produces approximately 30 million BOPD. Although OPEC may attempt to collude and control oil prices, world history has repeatedly proved that global cartels generally cannot control markets for any sustained period of time.

This article is not about geopolitical forces, but one can quickly see that OPEC members have distinct cultures, governments, customers, and priorities, as well as different production and reserve replacement costs. Hence, it is unlikely, and perhaps even unrealistic, for OPEC members to uniformly agree on production quotas and then expect each member country to behave accordingly. Therefore, it is probably a good assumption that global oil prices will submit to global market forces; i.e., oil prices will likely continue to depend on the supply and demand equation of competing producers and consumers.

The Reasons for a USD 30–60/bbl Range

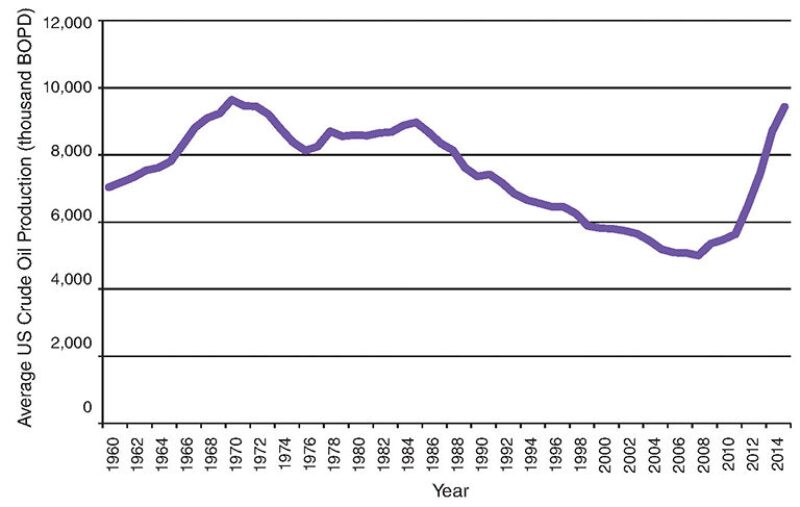

Why can one expect prices to fall in the range of USD 30–60/bbl as previously suggested? The biggest reason is the supply trade-off between conventional and shale oil production, combined with fundamental investment economics. To first understand this one needs to look at the domestic oil production of the US vs. time (Fig. 1).

Although oil prices spiked from the late 1970s into the early 1980s (Fig. 2), domestic production for the US moved minimally. However, during the strong oil price period from 2006 to 2014, US oil production increased from 5 million BOPD to 10 million BOPD due to shale oil. Moreover, it is now widely known that the US has 78 billion bbl of technically recoverable shale oil.

The investment economics of US shale production is easy to describe in terms of option pricing. Simply put, when the break-even, or option “strike” price, moves above where it is economically viable, the acreage owner can exercise its option to make a profit by drilling. This situation begs a few simple questions that can be easily answered.

First, what strike price is necessary to add shale oil production in the US? From a wide variety of sources and dependent on acreage location as well as other factors, the strike price of US shale oil ranges from USD 30/bbl to USD 50/bbl. Therefore, when the oil price moves above the particular producer’s break-even point/strike price, that producer can be expected to drill.

Second, how much production can US producers add as the oil price increases? Although all 78 billion bbl of technically recoverable shale oil may not be financially viable at USD 30–50/bbl, it takes only 0.365 billion bbl, or 0.5% of the 78 billion bbl, to add 1 million BOPD of production in a year.

Third, are an adequate number of drilling rigs and fracturing crews available to exploit the shale oil in the US? The answer is a simple “yes.” Specifically, the US has a total inventory of 1,600 drilling rigs, a sizeable percentage of which can drill shale wells, and the current number of active domestic rigs is approximately 400. Therefore, the US has ample rig capacity to seize drilling opportunities as conditions warrant.

This raises the question: “How many drilling rigs does it take to add, for example, production of 1 million BOPD?” The answer to this is straightforward and simple.

For example, if the oil price is USD 40/bbl, the required payout time 18 months, the royalty 3/16, the cost to drill and complete a shale well USD 7 million, and the production cost USD 8/bbl after drilling and completing a well, it takes:

(1−3/16)×(USD 40−USD 8)×(average BOPD for an 18 month payout)×365×1.5=USD 7 million

Thus, with the above cost and price structure, the average daily production rate for 18 months required for one well to satisfy the above economic equation is 491 BOPD. To simplify the equation, assume one drilling rig can add 500 BOPD per well, with the initial production rate being higher and the 18-month end rate being lower.

If one next assumes it takes 6 weeks to drill and complete a shale oil well, and if fracturing resources are available upon demand, one rig can drill approximately 8 wells per year. Hence, one rig is capable of adding 8×500=4,000 BOPD in a year. Therefore, it takes approximately 250 drilling rigs to add 1 million bbl of oil per day to the production capacity of the US.

With 1,600 domestic rigs available and approximately 400 rigs currently running, it is easy to see that the US has hundreds of rigs that could be put to work, as conditions warrant, and quickly add substantial production, thus putting the resulting downward pressure on oil prices.

As prices move higher, more producers will pick up drilling rigs to add production, make a profit, and supply markets with oil. And as prices move lower, producers will release rigs, allowing production to fall with natural decline, until global production falls to a point where demand again drives prices higher.

One may ask: “Why is the expected range USD 30–60/bbl when the common strike price for shale oil is USD 30–50/bbl?” In short, the USD 50–60/bbl zone is a reasonable buffer range. Should one also add a lower buffer range of USD 20–30/bbl?

Probably not, because global reserve replacement becomes exceedingly difficult below USD 35/bbl. Again, one should look at the USD-30/bbl and USD‑60/bbl price marks not as absolute borders, but as the range that contains most of the bell curve for sustainable oil prices.

In summary, production capacity, natural decline, prices, and drilling will move together to supply market demand. The world, in totality, generally operates on a capitalistic market supply and demand equation that has significantly influenced all aspects of global life and economics for centuries, if not millennia. Of course, low-cost producers will always have an advantage.

Other Considerations

One may argue that oil is different because a small number of producers “control” prices. However, if one compares the oil and gas industry with other industries, it is not unusual for two suppliers, in this case Saudi Arabia and Russia, to have a 25% market share.

Another argument is that the production economics in the Middle East are far more favorable than elsewhere in the world. This is true, but it is nothing unusual for a small number of suppliers to have an economic equation that is better than their competitors. For example, a farmer can raise wheat in West Texas, but the farmer with land in western Kansas will have a significantly better economic equation for wheat production than the farmer in West Texas.

One may also wish to bring political stability into the discussion. But again, political stability, or lack thereof, has always been a factor in economic equations. From the government side, the possibility of economic gain will always be an incentive to promote political stability. And from the investment side, companies will pursue business in politically unstable regions if the reward is worth the risk.

Technological advances have made shale oil production viable, given an adequate oil price. And it is safe to assume that technology will continue to advance. However, a 1,500-millidarcy, 7,000-ft deep, 40-°API oil reservoir will always have a competitive advantage over a 1-microdarcy, 7,000-ft deep, 40-°API oil reservoir. Why? It simply takes more horsepower and resources to extract oil from the 1-microdarcy reservoir than from the 1,500-millidarcy reservoir. But this is not the whole equation, as it is evident the world does not have enough 1,500-millidarcy oil production to fully supply demand.

Conclusion

Summarizing, it is likely that oil prices will range from USD 30–60/bbl for the foreseeable future. Short-term excursions outside of this range should not be surprising, but will probably not last for a sustained period of time. The reason for the likely USD 30–60/bbl range is the global interaction of producers and consumers, with a large potential shale oil supply that can be rapidly tapped as conditions warrant. A diminutive 0.5% of technically viable US shale oil can add 1 million BOPD of production for a year. The global oil supplier makeup is similar to that of other industries. Technology and political stability will factor into the equation, but this is nothing new. As with other industries, different suppliers have different economic equations, but this is common with the constantly shifting global economic order.

Rodney Schulz, SPE, is president of Schulz Financial, a retail advisory firm, and is the founder and exclusive instructor for Oil & Gas Economics and Uncertainty, a 2-day seminar taught both privately and through SPE. His oil and gas experience includes a wide range of engineering, finance, and operational responsibilities throughout North America for both major and independent producers as well as gas processing companies. Schulz’s expert witness experience includes work for a major oil company, the Federal Bankruptcy Court in Corpus Christi, and an international law firm. He has also served as the financial director/chief financial officer for an organization with 150 employees in six states. He earned a BS degree in petroleum engineering from the University of Kansas and an MBA from Duke University.