Energy development projects that affect local communities frequently face opposition. Industry insiders are often perplexed by this opposition and by the fact that their logical arguments seem to be ineffective at diffusing the opposition.

In the April 2013 Oil and Gas Facilities “Culture Matters” column, Jen Schneider addressed barriers to engagement, factors that make it difficult for industry insiders to communicate effectively with local communities. In this column, Jim Kent and Kevin Preister describe an approach to dealing with local communities that has proved effective.

— Howard Duhon, GATE, Oil and Gas Facilities Editorial Board

The takeover of a public park in Turkey to build a shopping mall. The raising of the public bus fare in Brazil. The government closing Greece’s major newspaper. What do these events have in common with the Keystone XL pipeline proposal? The authorities in these situations made a decision to impose a project solution without talking with the people who would be affected by the decision.

The Turkish government decided to take over a small public park to build a shopping mall without seeking imput/feedback from the community. In Brazil, raising the bus fares (mostly affecting poor people) seemed to be a reasonable approach to raise revenues for the upcoming 2016 Summer Olympic Games. In Greece, the shutdown of the government newspaper and the firing of a couple of dozen workers were done to demonstrate austerity to the European Union.

In the United States, the route of the Keystone pipeline, proposed to carry tar sand oil from Alberta, Canada, to Houston for refining, was planned to run across Nebraska’s Ogallala aquifer and sandhills, which are sacred cultural icons.

The problem? These decisions were made from the top-down on the basis of internal considerations, revealing a lack of capacity for dealing with emerging social realities across the globe. The decision makers neglected to understand that citizen engagement is a key to business success in today’s volatile world, where people are insisting on managing, predicting, and controlling their environments.

Small acts that seem inconsequential to government and industry can spark revolts and reactions that, in the cases of Turkey, Brazil, and Greece, have the potential to bring down the governments. The Keystone project could be lost because of the groundswell against the project stimulated by the routing mistake. Ten years ago, in a more formally structured world, these decisions would not have mattered. These days, when citizen resistance and mobilization are becoming routine and global, these decisions matter.

The JKA (James Kent Associates) Group has been tracking this emerging global trend for 30 years and has termed it “citizen-based stewardship.” It refers to citizens who claim ownership of geographic places and take it upon themselves, with or without government or corporate partners, to ensure that their families and communities are healthy and safe.

Transmission line corridors, alternative energy sites, and the proliferation of oil and gas development have improved our energy outlook, but have also affected people across the US. In particular, the hydrofracturing of wells for natural gas production has caused concerns in recent years. It is not difficult for a concerned public to find cause for alarm. For example, Jackson et al. (2013) recently published a study documenting the methane and ethane poisoning of a large number of wells within 1,000 ft of fracturing sites. The fracturing issue has now fused in national perception and become widespread throughout hydrofracturing areas, while also spreading turmoil to more traditional oil and gas activities.

Resistance has developed because much of the hydrofracturing is being done in geographic areas where citizens are not familiar with fossil fuel development. Their cultural experience and practices have done little to prepare them for the onslaught of drilling activity. When people have no mechanism in their daily lives to deal with intrusive change, their only avenue for relief is reaction and resistance. Studies such as the one cited earlier add fuel to the fire when the development company has no citizen connections or engagements to rely on for interpretation of the findings. With no mechanism for communicating, the company is vulnerable not only to local resistance, but also to national groups that will use these studies to benefit their causes.

The top-down approach to project design is still in place. Projects are designed by engineers from locations miles away from the site. It is common practice to expend extensive engineering effort early in a project during the front-end engineering and design (FEED) phase. This design process leads to only the technical issues being addressed. The engineering culture wants the design firmly in place, with all the technical details worked out, before going public for review (Schon 1983).

Companies prefer to hold their cards close to their chests to avoid revealing information to residents who they fear could stimulate conflict. For example, the people who negotiate the rights-of-way for projects have an incentive to keep things quiet while they interact with landowners. Public relations personnel recognize that failure to be transparent invites suspicion and mistrust, yet they are constrained by corporate cultures that emphasize control of the development process.

Such approaches are no longer productive or profitable. Corporate neglect of citizen engagement is a costly affair for everyone.

Clash of Two Cultures

The situations described illustrate cultural clashes between the communities’ horizontally organized systems vs. the corporations’ vertically organized authority—clashes of perceptions and practices. The community is oriented to caretaking and survival, and the industry is oriented to economic gain.

In this article, we show that the cultural clash is not inevitable. The two systems must come into harmony if the oil and gas industry is to remain productive and profitable. When dealing with communities, it is essential to recognize that the adage, one size fits all, is not applicable. Just as each project is technically different, each community is different—with different histories, beliefs, and issues.

In any cultural system, life is predictable through routines and language. As change occurs, people need time to adjust within their cultural settings. People continually deal with emerging issues and solve them. It is when there is intrusion, without recognition of how the culture has previously handled change, that projects are at risk.

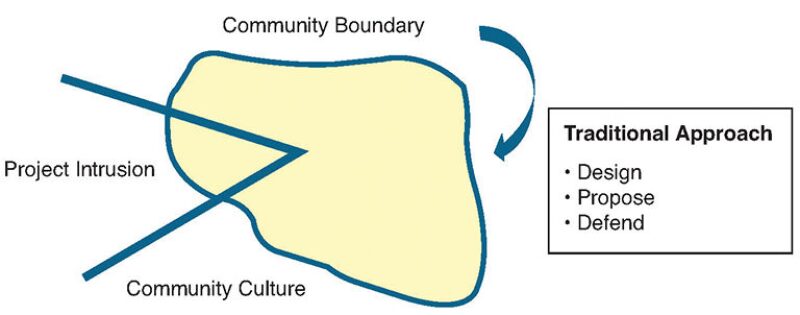

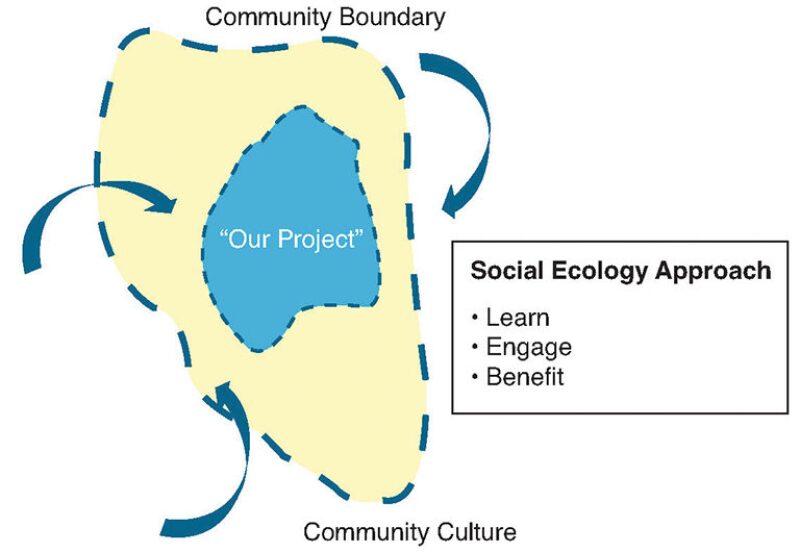

Figs. 1 and 2 show the old and new ways of doing business. The old (traditional) approach is to design in isolation, propose the design, and then defend it against opposition. This approach is depicted as a wedge into the community, fostering disruption and mistrust, and creating local issues. If these issues go unresolved, they offer outside groups the opportunity to take advantage of unresolved citizen issues in the pursuit of their own agendas, leading to formal opposition groups such as occurred with the Keystone XL pipeline project.

The new model gives residents a voice and emotional ownership, which in turn gives the company a social license to operate. If intentional efforts are made to resolve legitimate citizen issues early in the design stage and to optimize the local benefits of a project, citizen ownership through absorption will serve as a buffer for the project against outside forces.

Preventing the Escalation of Emerging Issues

The key to understanding culture from a practical point is to learn about the issues that are currently present in the community and/or that the project may create. Community issues do not begin as uncontrollable events that are guaranteed to stop projects. Instead, they emerge as legitimate questions that citizens have about a proposed project.

It is not the case that the local community has formed a steadfast or universal opinion. Rather, people are simply seeking answers to basic questions, including: What will this project do to my property value? Will it increase traffic? How will it affect air and water quality? How many people will be hired locally? Will the project enhance the growth of local businesses? Will community-based training programs or college curriculums be offered to prepare our citizens and youth for employment and advancement opportunities? Will the company ensure local benefits from the project, such as reduced electric rates? Will there be assistance for establishing businesses to service the project?

When the basic questions are not addressed, emerging issues can easily escalate to actual ones. By this point, people have formed their own opinions, and the community dialogue changes from seeking information to developing positions. The questions turn to negative statements, such as: This project will ruin our property values. The traffic and noise from this project will be unbearable. Children and seniors with asthma will suffer, and the incidence of cancer will increase. They will not be contracting or hiring locally. Local businesses will not benefit from this project and may actually lose revenue. The skills necessary for employment are beyond most of our citizens. The company just wants to exploit our community for profits.

These sentiments may not be based on facts, but without community engagement, perception becomes reality.

If the actual issues are not addressed effectively, events will only become worse. Community opposition is often joined by opportunistic ideological groups, followed by political positioning. Polarized positions are taken toward the project, and the opposition quickly moves it into a disruption. By this point, the project proponent has virtually lost the ability to resolve the individual and community issues. The issues that could have been resolved, had the citizens been engaged in the early phases, are taken over by outside forces who oppose development at anytime, anywhere.

The Solution: The Social Ecology Approach

The social ecology approach involves attention to the community on three concepts: a descriptive approach for understanding informal networks and their routines; understanding human geography, or the ways that residents relate to their neighborhood and community areas; and issue management, which creates alignment between citizen interests and company interests. Social ecology is a science of community based on cultural processes operating in any geographic area or in any resource company.

The following five rules help in gaining an understanding of local cultural issues:

- You, as a project proponent and an outsider and guest of the community, have a responsibility to learn about the community before acting.

- People know more about their environment than anyone else. It is the job of the project manager to bring forward this knowledge and perception to make use of it.

- The project proponent must ensure that citizens can predict, control, and manage changes in their environment so that the effects of the project are absorbed into the fabric of the community and the benefits are optimized.

- People trust day-to-day and face-to-face communication, which is essential if the project is going to fit the community.

- Whoever understands the human and physical geography that creates the community’s sense of place controls the project outcome.

Procedures to implement the five rules of culture change are:

- Contact and engage with citizens early to avoid surprises. Community engagement must be at parity with technical disciplines in tactical and strategic project decision making. For example, extensive technical work during FEED should be accompanied by extensive community engagement.

- The objective of early engagement with the community should be learning. Learn the informal networks of a community and its communication patterns as the basis for engagement. Learn the language that people use to communicate on a routine basis and use that in project development language.

- Engage the affected people directly. Do not rely on formal groups or stakeholders in understanding community interests. Do not use public meetings as a means of initial citizen contact. Use the gathering places of a community to foster effective project communication and as a means to become an insider to the culture.

- Understand human geographic mapping systems that reflect cultural boundaries, or the ways that people identify and relate with their landscape, to foster responsive siting of facility and corridor projects.

- Deal with citizen issues at the emerging stage of development when the costs of time and resources are lowest, rather than allowing issues to reach the disruptive stages.

- Make use of local company staff, when possible, at the design and implementation stages and provide management support in assisting them to create an approach from the bottom to the top.

Conclusion

The social risk to project success has become too great for the oil and gas industry to not formally recognize and systematically act upon the underlying causes of how citizens’ participation often moves from support to active opposition. Whether the project is on public or private land, it deserves this level of attention.

Since community relations are now linked to project success, upfront engineering should include upfront community assessment and the establishment of an informal word-of-mouth communication system. Knowing about culture and its influences on citizen behavior presents a creative and successful way for industry leaders to steer their projects around pitfalls and other surprises that cause delays or stop projects altogether.

Understanding the culture of a community facilitates collaboration in a manner that directly benefits the citizens and keeps a project on schedule, saving time and money. The true currency of the present and future is the sustained goodwill that a project creates and maintains with its communities of impact.

For Further Reading

Jackson, R., Vengosh, A., Darrah, T., et al. 2013. Higher Levels of Stray Gases Found in Water Wells Near Shale Gas Sites, http://www.nicholas.duke.edu/news/higher-levels-of-stray-gases-found-in-water-wells-near-shale-gas-sites (accessed 7 July 2013).

Kent, J. 2012. The Promise and Peril of Corridor Expansion, http://www.jkagroup.com/Docs/IRWA-Corridor-Expansion-2011-12-05.pdf (downloaded 7 July 2013).

Schon, D.A. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Basic Books.

| James A. Kent, president of JKA Group, is a global social ecologist and an advocate for using culture-based strategies when introducing site/corridor projects to local communities. He has expertise in crafting empowered partnerships between corporations, communities, and governments. He can be contacted at jkent@jkagroup.com. |

| Kevin Preister is the director of the JKA Group’s Center for Social Ecology and Public Policy. He has conducted issue management programs for corporate and government clients for 30 years and has specialized in natural resource management with the US Bureau of Land Management and the US Forest Service. He can be contacted at kpreister@jkagroup.com. |