Fugitive methane emissions at shallow-water facilities in the US Gulf of Mexico (GOM) may occur at a significantly higher rate than what is typically documented at US onshore facilities.

This is according to a new study led by nonprofit organization Carbon Mapper, which said its recent findings underscore the need for further offshore emissions monitoring and the effect mitigation efforts would have in the shallow-water sector.

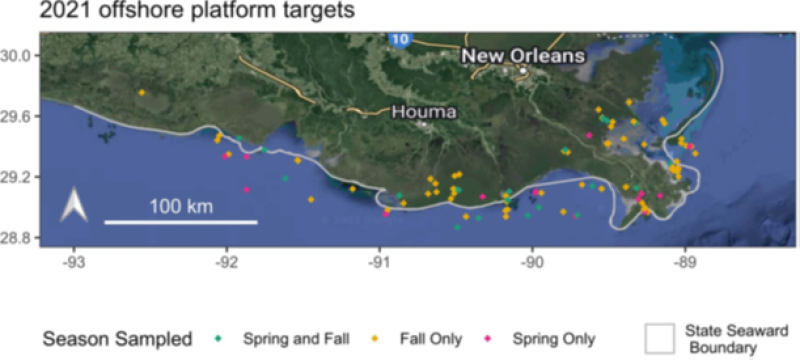

Conducted during the fall and spring of last year, the study used aircraft-based monitoring to survey 151 shallow-water platforms and hub facilities, or about 8% of all US shallow-water oil and gas assets.

The researchers found that many of the locations had methane loss rates—the observed emissions compared with reported natural gas production—of between 23% and 66%.

For comparison, other recent studies have calculated loss rates of 3.3% and 3.7% at onshore production sites and facilities in the Permian Basin, which spans Texas and New Mexico.

Other contributors to the study include the University of Arizona, Arizona State University, University of Michigan, and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Researchers from these institutions highlight that their study represents the first large-scale application of a new remote emissions-sensing technology that is able to quantify emissions over water and tie them back to specific infrastructure.

Traditional spectroscopy methods for emissions monitoring are difficult to execute offshore because of the darkness of the water. In this study, the researchers relied on using the reflection of the sun off the water, or the sun glint, to provide a sufficiently large signal of methane.

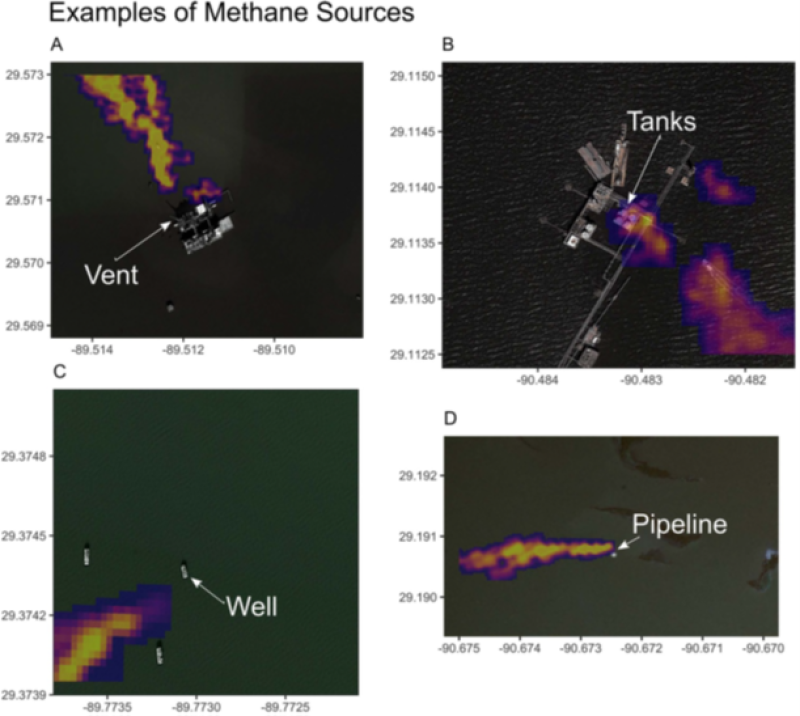

Also, the imaging spectrometer used was developed by Arizona State University’s Global Airborne Observatory and is able to detect methane sources to about 15 ft of their source from an altitude of 18,000 ft.

Shallow-Water Super Emitters

Among the big takeaways is that 62 of the 151 platforms in the offshore study appear to qualify for super-emitter status, which is defined as having observable methane plumes of at least 10 kg/h.

Carbon Mapper and its partners report in the study that, “The cause of the exceptionally high loss rate for this set of platforms at this time is unknown.”

There are, though, some common traits shared by outsized sources of emissions in the oil and gas industry. In the onshore sector, it is commonly discovered that low-production wells often have the highest loss rates; this new study suggests the same may be true for the offshore sector.

Carbon Mapper said the median production of wells it surveyed in the fall of last year was almost 19 BOE/D in US federal waters while just 3.26 BOE/D for wells in state waters. In the spring, wells surveyed in federal waters had a median output of 33.7 BOE/D compared with 4.6 BOE/D for wells in state waters.

Average rates for all GOM wells in the fall and spring were 50 BOE/D and 43 BOE/D, respectively.

Long-Duration Emissions Are a Problem

Most of the fugitive emissions observed in the Carbon Mapper study were found to be coming from storage tanks, satellite wells, pipelines, and vent booms. As the study points out, this underlines how a small number of sources tends to account for the majority of the emissions found in such studies.

The researchers also argue that the persistence of methane emissions further contributed to the super-emitter behavior observed. They calculated that, on average, the platforms and associated infrastructure that were leaking methane were doing so 63% of the time.

The figure is based on multiple surveys at many of the targeted platforms. In each of the fall and spring campaigns, researchers conducted flyovers at 40 platforms at least three times and found that 34 of them had a methane plume on at least one visit.

Researchers also selected 20 platforms to be surveyed during both spring and fall and found eight had methane plumes during each season. This suggested that those eight sources were likely emitting for at least 6 months while the other 12 appear to have had shorter-duration releases or are intermittently emitting.

The aspect of persistence is an important one because a single event that occurs infrequently could be less concerning than smaller leaks happening on a constant basis.

To this point, the study noted that 12 of the sources had methane emission rates that surpassed 1,000 kg/h. Then, upon subsequent observations, only seven of these sources were found to have sustained emissions above that threshold.

Those seven locations represented just 11% of the total number of emitting platforms in the study but more than half of the total emissions recorded. In citing an onshore study of similar scope, the researchers noted that only 1.3% of sources (18 of 188) were found to have sustained methane emissions rates above 1,000 kg/h.

“This illustrates how significant the high-persistence values are in the shallow-water [Gulf of Mexico] study,” the researchers wrote, adding that 2–3 airborne surveys a year might be adequate to properly estimate persistence.

Among the broader points that the study makes is that more emissions surveys need to be conducted offshore. It cites other airborne studies from the North Sea and Norwegian Continental Shelf that found emissions at offshore platforms tend to be higher than what is reported.

The study authors write that underestimating methane emissions from offshore production facilities, which account for 30% of the world’s oil and gas production, “could significantly impact” the global budget for methane emissions.

The researchers said the study will aid in future attempts to use sun glint to measure methane concentrations at offshore oil and facilities. Carbon Mapper said it also plans to follow up with the launching of a new hyperspectral satellite constellation that it is developing with Planet Labs and NASA’s JPL.