The global nature of the workplace in the petroleum industry has introduced a new challenge to our competitive business landscape: the development of soft competencies as a critically important element in driving productivity. Soft skills as an element of sustainability brings success to individuals and organizations in a variety of workplace activities, such as forging alliances, creating a team harmony that produces collaboration and innovation, and managing and using the human and system components to influence outcomes and achieve business goals. As the nature of workplace engagement shifts, soft competencies provide individuals with the ability to manage the social, cultural, technical, and environmental expectations of both the individuals and their organizations.1

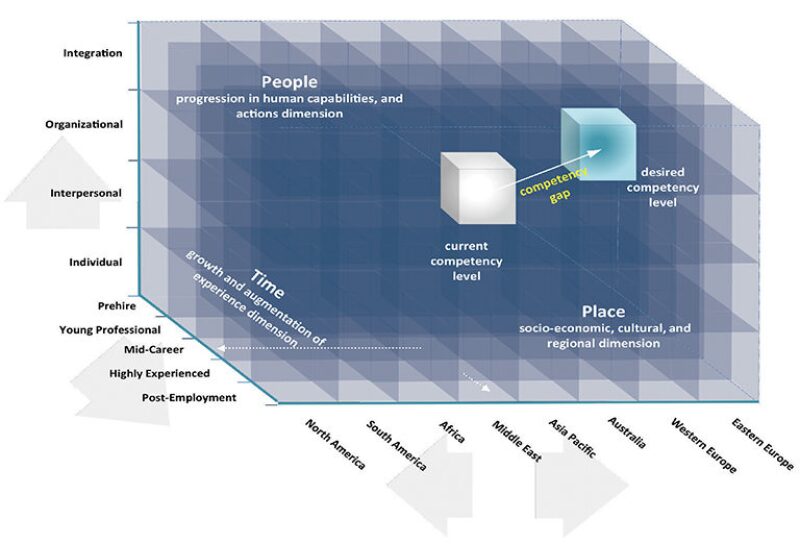

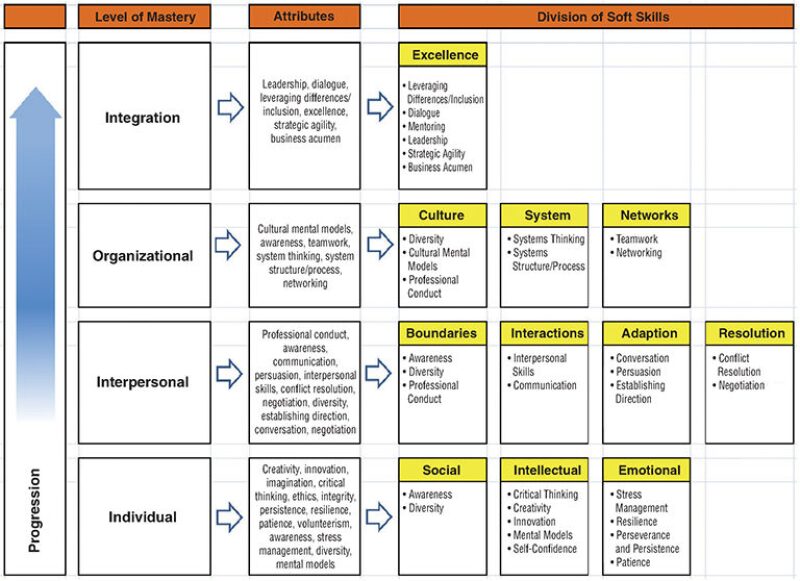

In an October 2013 JPT article,2 the Soft Skills Committee of SPE introduced the Soft Competency Matrix, which is governed by attributes stemming from progression in people capabilities and actions; growth and augmentation of human capabilities with age and experience; and socioeconomic, cultural, and traditional dimensions (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 above). The authors noted that while the first two elements were governed by a continuing journey through time and personal maturity dimensions, the changes in the third element could be abrupt depending on the attributes needed for the new work assignment.

Global Challenge for SPE

The use of the matrix allows individuals to measure their soft competency level against the expectation to identify current gaps and chart an improvement path. This is obviously a starting point for engagement to better manage and prepare for the ongoing changes and to save time to autonomy for our industry professionals. Moving from a world primarily defined by the location business needs and technical capabilities to one that also emphasizes soft competency as a requirement for success allows the employers to assess the competency gaps in their employees’ soft skills.

There are two major challenges for SPE to help these professionals achieve the expected levels of soft competencies:

- Applicability of the identified attributes at the global level

- Effective expansion of soft skills discussions and training around the world

It is recognized that the methodology described in Figs. 1 and 2 will have to be refined for various regions in the world based on regional cultures, traditions, and ways of life. We must emphasize that the intent of the Soft Skills Committee is not to standardize soft competency best practices globally, but rather to create a framework whereby productive conversations can start. The committee understands and adheres to the idea that soft competencies are practiced according to regional cultural traditions and preferences, and their best practices are determined only by the people from each culture.

To develop a better understanding of the nature and extent of the global variations, the committee conducted a workshop attended by 18 international professionals from a variety of oil industry disciplines including engineering, geology, and information technology. The participants were selected from among those who were born and raised in Asia Pacific, South and Central America, western Europe, eastern Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. They came to the United States as adults for advanced studies or to work. The participants were asked to examine the relevance and validate or modify the soft skills attributes listed in Fig. 1 for their regions. The conclusions from this exercise were:

- Although the majority of the attributes listed in the soft skills matrix were common among regions, there were a few unique attributes to be added for each region.

- Some of the attributes tend to have different connotations in different regions.

- Same attributes may be practiced in different ways.

- The degree of emphasis for some attributes is different for different regions.

- Even within the same region and often within the same country, background and cultural differences do exist, which in turn and to various degrees result in variations noted above.

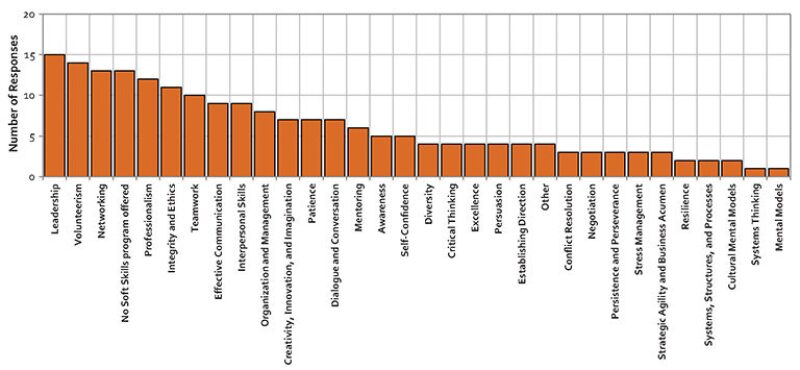

An effective global expansion of soft skills discussions and training throughout the industry is another important challenge for SPE. An effective expansion means reaching a critical mass in the number of discussions and training of soft competencies to create a continuity and momentum in such a way that individual events around the globe become interconnected, relevant, meaningful, and consequential to others. Early this year, the committee conducted a survey of officers in SPE sections and student chapters worldwide to gauge the status of soft skills programming. Although the survey is still under way, the preliminary results indicate that while there is a demand for SPE programming on soft skills (Fig. 3), there is a lack of substantial and organized process by the Society to make such programming available to members as an important element of professional growth.

To build the momentum needed to propel soft skills to an equal footing with technical competencies, activities, discussions, and participation in soft competencies need to start at the members’ level and within SPE sections and student chapters. To achieve success, the discussions and training in soft competencies cannot be top-down driven. Bottom-up initiatives will be necessary to create the critical mass needed for effective global expansion. The committee’s role1 will be that of a facilitator to assist in coordination of these activities, provide ideas, enable access to regional experts, and energize and maintain the activities within the soft competency world.

Path Forward

With the development of a soft skills matrix, the next step will be studying the issues critical to our industry professionals including gender diversity, professionalism and leadership, and ethics. Organizing discussions on soft skills topics in conferences, establishing a distinguished lecturers program, and in particular, the development of a robust training platform will be part of this effort as well.

The need for a robust soft competency training program is in line with SPE’s identified strategic priorities3 of capability development (to support the industry in dealing with the “big crew change”), knowledge transfer, promoting professionalism and social responsibility, and public education about the petroleum engineering profession and industry issues. The Society has already taken important first steps in establishing the SPE Leadership Academy, with a number of pilot short courses under development.

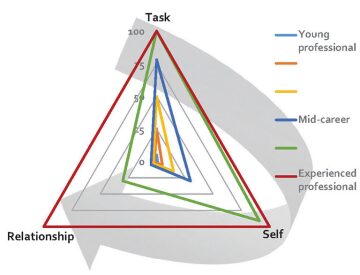

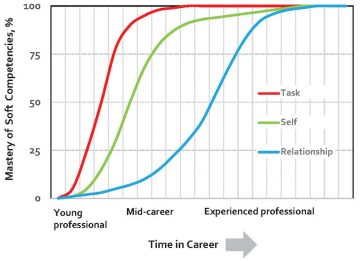

The design and implementation of a training program will have to be compatible with members’ demand. For an industry young professional, the road to achieving autonomy starts with developing task proficiency, followed by gaining self-awareness as a secondary capability, and eventually developing proficiency in later years to build and manage a complex array of relationships. These are necessary appropriate adaptive capabilities that leverage technical know-how in completing more complex tasks. To use a petroleum engineering analogy, if technical professionals are limited in their development of soft skills, it might be compared to a skin effect, which limits a well from achieving its full potential. The sequence and the pace of soft competency growth and its trend are shown in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5.

Early in their careers, technical professionals focus on the development and acquisition of technical skills to solve problems and deliver results.4 The early work assignments are generally constrained in terms of complexity and risk to the team or business unit. This allows for individuals to develop and to test the use of technical knowledge in general problem-solving endeavors. Thus, the focus tends to be on the achievement of the task through technical know-how. With time and demonstration of technical competency, projects and assignments grow to evolve in complexity and wider system implication. The problem solving and implementation of solutions not only have greater implications for the overall performance of a team or a business unit, but also require the cooperation and engagement of other stakeholders.

The increased complexity creates a potential for larger and longer-term business results with a corresponding risk of failure. The failure with more complex projects is not only relative to immediate business results, but also in the sustainability of relationships and business performance. Thus, more complex problems require greater self-awareness and management of relationships. Practically, the sustainable outcomes now require not only technical competency, but are dependent on how a technical professional interacts with others. To complete the triangle, the development of two additional capabilities is necessary: self-awareness and relationship management.

Developing self-awareness and the capability of recognizing and developing longer-term aspirations as well as getting clarity of one’s fundamental beliefs that limit and expand options for solving complex problems is an essential starting point during the first 3 to 5 years of a career.

The capability of leveraging and managing relationships can be summed up in the following question: How can I understand and help the other team members meet their needs and aspirations so that I have a greater chance of getting my aspirations met while achieving the task at hand?

Conclusion

While technical competencies deal with impersonal aspects of the work environment, the soft skills domain revolves around the professional and personal relationships in pursuit of business success. Recognizing this fact, this article describes the progress on providing a path forward for closing the soft competency gap, and the committee’s focus on globalizing the soft skills matrix. To achieve these goals, several clarifications are necessary. The clarifications are viewed as opportunities and challenges.

Opportunities are:

- Because of its global presence, SPE has the opportunity to facilitate the development of soft skills competencies in ways that suit the cultural and social expectations of specific regions. SPE has a long history and experience of facilitating the development of technical competencies worldwide, while balancing the generally accepted technical standards and specific needs of regions and business conditions. This experience and capability can now be used for soft competencies in moving from a 2D competency measured local work environment to a 3D competency measured global work environment.

- The incoming contingent of industry professionals is more keenly interested in developing their capabilities not only in technical disciplines, but also in the soft skills arena.

Challenges are:

- The mixture of the emerging importance of soft skills and the inherent breadth of disciplines (communication, diversity, leaderships, ethics, cultural preferences, etc.) within the soft skills domain, combined with the variety of ways of application and valuation creates substantial complexity.

- The barriers that continue to divide and create conflict among people (diversity including gender, race, beliefs, etc.), and biases about our differences and similarities will affect the pace of expansion of soft skill competencies.

- A fundamental paradigm that we hold regarding soft skills is that both the individual and system need to exchange relevant information required for adaptation, delivery of desired results, and sustainability of both the individual and the system. As such, communication is an essential vehicle for learning and delivering the results we are seeking to achieve.

- Over its history, SPE has mastered the nuances of language differences in the technical domain; in the world of soft skills, these differences will require more special attention. Our languages contain and encapsulate the cultural norms and expectations and thus will require broader awareness and sensitivity. It is important to remember that SPE does not dictate the whats and hows of communication, but provides the means for raising the awareness of cultural differences.

- It is recognized that the soft skills matrix was initiated within the North American cultural system and thus requires adjustments for the nuances present in the various geographic regions. To do this, each region has to make it credible in ways that work for that region, thus emphasizing the critical importance of initiating through and engaging the grassroots membership in this endeavor.

- Unlike the general transfer of technical skills, soft skills require the interaction between social constructs and individual knowledge, which in turn inform each other. Wisdom and knowledge are not held by an expert but are created through the interaction of members in pursuit of shared objectives.

- There are regional constraints and variations in the cultural capacity to adapt, which clearly defines what is negotiable and what is not.

- Recruiting regional soft competency experts to assist with the development of short courses and training will be a continuing challenge.

References

- Fattahi, B., Howes, S., Milanovich, N., et al. 2012. Soft Skills Council: A New SPE Initiative. J. Pet Tech 64 (8): 52–55.

- Fattahi, B., Milanovich, N., Howes, S., et al. 2013. The Elements of a Soft Competency Matrix. J. Pet Tech 65 (10): 92–102.

- SPE Strategic Plan 2013–2017. March 2013.

- Milanovich, N. and Eagleson, G. 2014. Learning: The Ultimate Transferable Skill. The Way Ahead 10 (2): 22–23.