Critics occasionally dismiss the potential of unconventional oil and gas reserves as a flash-in-the pan trend that will pass, but a panel of experts said the reserves are a lasting resource, one that promises oil and gas production for decades to come. To make that happen, however, the industry needs to focus on the technologies that enable the development of those reserves.

Stephen A. Holditch, professor emeritus at the Harold Vance Department of Petroleum Engineering at Texas A&M University, said that most of the world’s production to date has focused on a traditional reserves base that is relatively easy to extract. The conventional resources, where oil has migrated to high permeability reservoirs, are harder to find, but easier to develop. “Once you find a high permeability reservoir, you just have to drill a vertical well, perforate it, and it produces at … economic rates,” he said.

Speaking at a webinar sponsored by SPE’s Reservoir Description and Dynamics Advisory Committee, “New and Emerging Technologies for the Oil and Gas Production of Shale,” Holditch said that much of the future production will focus on unconventional reserves, including coalbed methane, shale, and heavy oil. Unconventional resources are often the opposite: in good supply, but harder and more expensive to develop. To develop unconventional resources, the industry needs more advanced technology, higher oil and gas prices, or both, he said. Horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing are two of the technologies that allow the industry to develop unconventional resources. “Low-quality reservoirs can be enormous,” he said.

To cite an example of the progression of conventional to unconventional reservoirs, Holditch pointed out that 20 or 30 years ago, the industry was developing the Austin chalk, a reservoir that was considered large by the standards at the time. The industry knew that the Eagle Ford Shale was the source rock for the Austin chalk. Today, the industry is aggressively drilling into the Eagle Ford.

Based on the assumption that all natural resources have a log normal distribution, the industry will be kept busy in unconventional resources for decades to come. “We should expect that in the next few decades, we are going to see a lot of unconventional oil and gas development in virtually every basin in the world,” he said. “This is going to be a global phenomenon, not just something confined to the United States.”

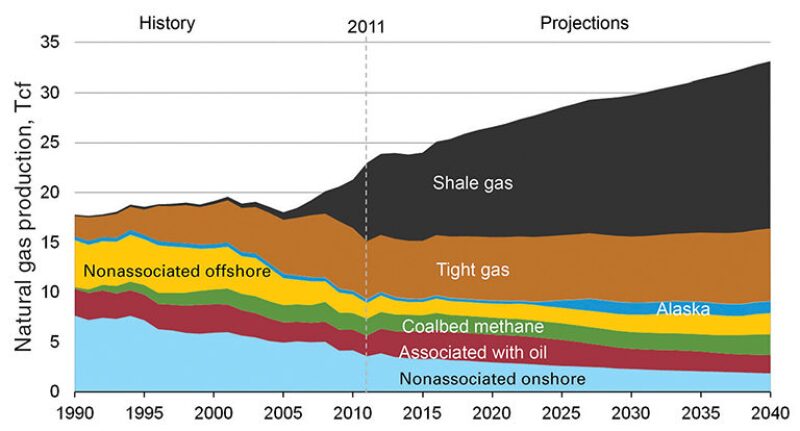

The expected production of hydrocarbons in North America is expected to increase dramatically in the coming decades. “Fully 75% of the gas we will produce in the US will be from unconventional reservoirs,” he said.

Based on maps of North American shales, Holditch and his graduate students at Texas A&M have modeled the potential for world oil and gas reserves based on worldwide shale formations for development over the next 30 years. Using this methodology, researchers have estimated that there are about 57,641 Tcf of technically recoverable natural gas reserves in place worldwide. Within North America, researchers have estimated that about 8,614 Tcf of natural gas reserves are technically recoverable (Fig. 1).

The term “technically recoverable” means the industry knows the location of the reserve and has the technology to develop it. It does not necessarily mean it is economical to produce, he said.

“The bottom line is there is several hundred years of gas production in tight gas reservoirs and shale gas reservoirs for the world that is technically recoverable,” he said.

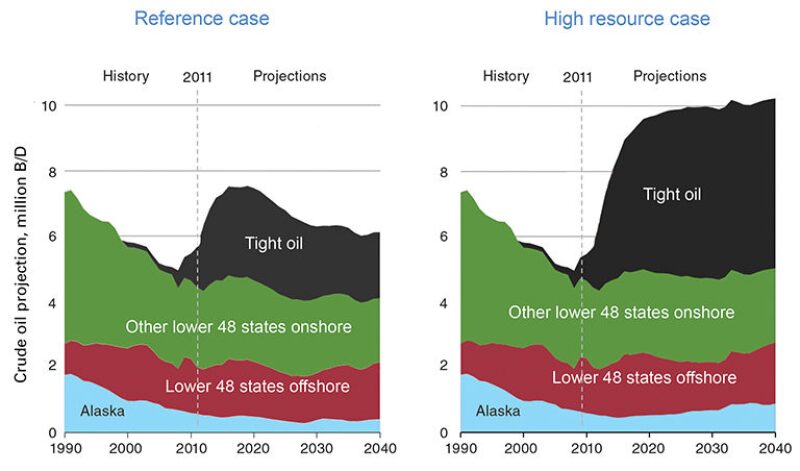

The outlook for oil is similar. The US Energy Information Administration has published estimates that North American production of tight oil is projected to rise from 5 million to 10 million BOPD over the next 20 years (Fig. 2). “Things look very bright in terms of resources,” Holditch said.

One of the barriers to developing these reserves is the high cost of finding and developing them. “These wells just cost a lot of money to drill and complete. We’ve got to come up with a way to reduce those costs. The new technologies that we should expect over the next few years are those which solve some or all of the problems with developing tight oil and shale gas,” he said.

Hydraulic fracturing, measurements of horizontal wellbores, remote sensing, reservoir analysis, and reservoir modeling are areas that will help the industry pull operating costs down. Geosteering is another area of research that will help operators control their costs. “We need to look ahead of the bit and we need technology, which will help us keep the horizontal hole in zone,” he said.

George King, an engineering adviser at Apache, and George Moridis, a staff scientist at the earth science division of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, described some of the challenges to the emerging technologies used to develop these resources.

The development of unconventional resources will require some unconventional thinking that was not applied to conventional reservoirs, King said. The design of hydraulic fracturing for unconventionals differs from conventionals. “In conventional reservoirs, we were used to looking at all of the reservoir being able to produce relatively uniformly,” he said. That is not necessarily the case in unconventional reservoirs. “We know that the flow is going to be very slow,” King said.

To cope with that problem, researchers are looking for ways to reduce the viscosity of crudes. “We need to understand where to put the hydraulic fractures that would give us the best economic and recovery response for the money and equipment we are using. We need a much better understanding of how fluids flow through the formation,” King said.

Moridis said much of the current research in the oil and gas industry is to maximize production and recovery from unconventional resources, including shale, tight oil, tight gas, and coalbed methane. One area of research is the ability to accurately estimate reserves from unconventional reservoirs. In addition, researchers continue to stress environmentally sensitive ways to develop these resources.

A recoding of this webinar can be viewed here.