Project management in the oil and gas industry comes with a unique set of challenges involving the management of engineering, technology, science, cost, schedules, procurement, risk, safety, personnel, and communication. Generally, companies’ approaches to “training” engineers to become project managers consist of mostly informal mentoring and the individual’s acquisition of lessons learned through his or her own work experiences.

Is the current method of developing project managers effective?

Anecdotal evidence from operating and service companies, contractors, and consulting engineering firms confirms a not-so-hidden secret: The oil and gas industry’s performance in executing megaprojects is dismal. A recent study of offshore megaprojects (Merrow 2011), reported that from 2003 to 2011, only 22% of offshore megaprojects could reasonably be called successful as measured by the fulfillment of promises made at the time of the financial investment decision. Real cost overrun was 33%, and execution schedule slipped 30%. In comparison, nonoil and gas development projects achieved a success rate of approximately 50%. Although not a stellar performance, it trumped the oil and gas industry’s performance.

Shortfalls in project management are pushing companies to seek ways to improve their project performance. Putting aside significant bottom line considerations, the industry’s growing complexity in projects, shortage of skilled people, and the expected crew change in the next decade signal the need for new approaches in improving the capabilities of project management.

Building on Management Successes

Wintershall, a subsidiary of BASF and Germany’s largest crude oil and natural gas producer, set up a project management support group in 2011, Operating in Europe, north Africa, South America, Russia, the Caspian Sea region, and the Middle East, the company’s growing portfolio of projects spurred its efforts to develop new methods of supporting and building a project management culture.

The support group—an identified, designated unit responsible for answering questions and providing guidance—was the result of a deliberate decision to strengthen the company’s project management for its increasing numbers of international and intensive capital expenditure projects.

“The main drivers for the initiative were the desire to facilitate communication and the exchange of knowledge across the generations, disciplines, and locations,” Patrick von Pattay, head of project management support at Wintershall, said.

Previously, each project manager worked in his or her own way, following best practices. “This might have been sufficient for the very experienced project managers, but definitely not for the newcomers to the discipline. Today, the tools and support that we provide combine the best practices in one fully integrated approach aligned with the company’s business processes. This allows getting up to speed quicker, improving project management quality, and aligning the projects for the company’s growth strategy,” von Pattay said.

Project Initialization

The company board’s commitment to project management and the setup of the support group was critical to the success of the project. Considering the group’s goal of “developing the support group with its future clients for its future clients,” definition of the objectives, and the scope of work were critical and included the cultural and organizational aspects of the company.

Mike Morrison, senior project management adviser at Wintershall, said, “Developing one common reference system for the company and promoting one project management language for worldwide application were the main objectives of the project. Conveying the support group’s goal of adding value in day-to-day operations was a key to acceptance of the program."

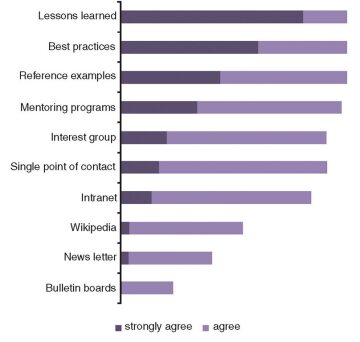

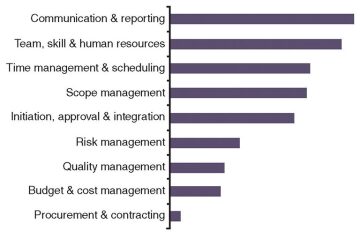

The project team interviewed 40 project and line managers to identify their expectations of and concerns about the project support group (von Pattay and Morrison 2012). The majority of the interviewees agreed that project management had a high strategic relevance and that the initiative would add value. The input from the interviewees resulted in a focused approach for the development of useful tools and best practices (Figs. 1 and 2). Identification and use of the existing solutions that had been proven to work, instead of reinventing the wheel, was important to gaining the acceptance of the most experienced project managers. The assurance and proof that the project’s intent was not to “teach old dogs new tricks” or “steal their know-how” lead to the realization that their knowledge was used to the benefit of the organization.

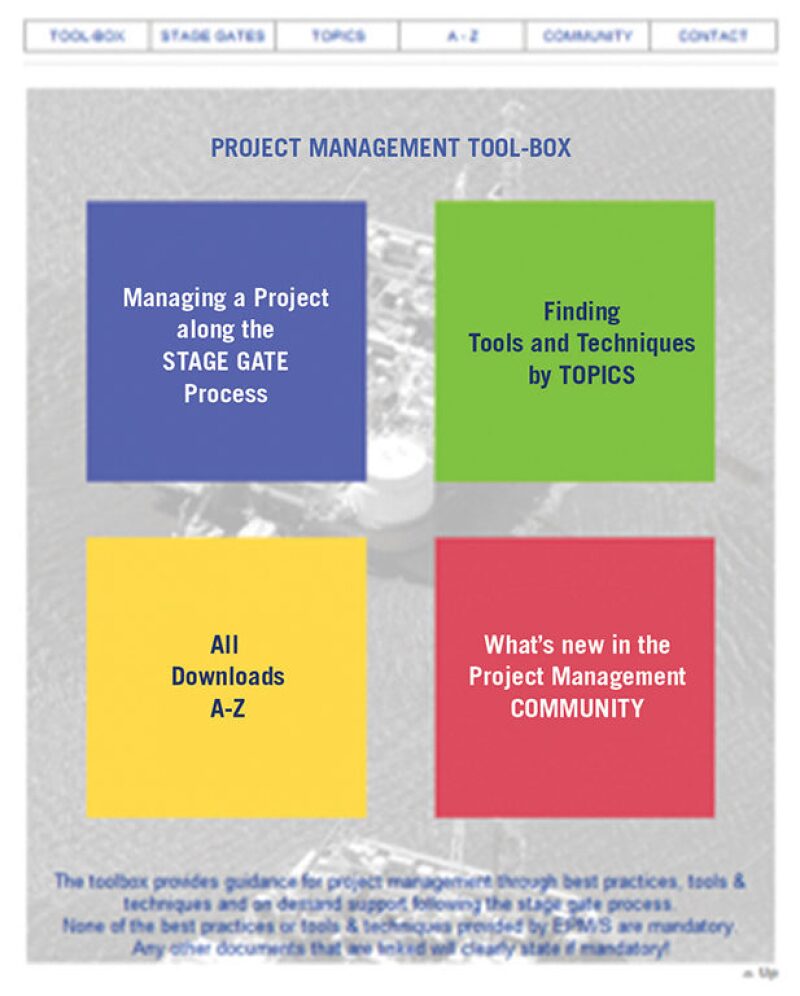

The use of an online toolbox (Fig. 3) and a social network for knowledge exchange was paired with on-demand coaching for competency management. Every project manager needs tools to manage risks, tract costs, or plan a project. According to von Pattay and Morrison, the more these tools are tailored to the project manager’s needs and made consistent throughout the organization, the more effective and efficient they are.

The project management toolbox was developed with tools presented in pairs—one for simple applications, and the other for complex applications. No “one size fits all” solution was found. The tools were kept generic and provided reference cases for their application in different projects. The emphasis was placed on the project methodology common to all projects, rather than on the differences in scope of projects. Tools were selected based on usefulness by different people from different projects and locations. The online toolbox includes a collection of examples of the tools applied in real projects as a reference and to provide guidance.

Networking and Knowledge Management

The interviews completed during the initialization stage showed that personal networking is the main means of knowledge management within the company. Von Pattay and Morrison reported that the personal networks would grow naturally through personal experiences over time and, therefore, be limited.

“You would learn project management as you went along and experienced it. That might have been great in some cases. In others, some aspects of a project may have been a useful learning experience, while others might have been a disaster. People may have been running projects with great schedules, but no organizational structure. Or projects may have had outstanding cost management, but lousy communication approaches. People just did it the way they experienced and learned it,” von Pattay said.

Enhancing and expanding the networking beyond the boundary of locations and disciplines was the goal of the creation of a Web-based community.

BASF’s existing online community for networking, knowledge sharing, and collaboration was used to set up “project management@Wintershall,” using the community options, blogs, and discussion forums for the exchange of experiences and knowledge. Morrison said, “Generally, 1% to 2% of the people on a social network are active. Therefore, you need more than 100 people to get a conversation going between two people. Ninety-eight other will just read a blog, but not comment.

“We now have more than 400 people involved with the social network, including BASF people. Our [Wintershall] community of project managers would not be large enough to sustain an active, engaged group. Opening up the social media to BASF helped us achieve critical mass and engage people with different ideas. Many of the BASF managers come from a facilities or research and development background.”

|

Progress of the Program and Looking Ahead

The program was introduced with a road show visit to all of Wintershall’s international locations. More than 600 people working in day-to-day operations were made familiar with the approach. All newcomers to the company are introduced to the program to make them aware of the available resources.

The online toolbox, which had 200 to 300 hits per month in the early phases of the program, now has 1,500 hits per month.

Training and development in project management continues to be a priority. The company’s goal is to have a certain number of project management professionals certified by the Project Management Institute by the end of the year.

Mentoring and coaching is a component of the overall initiative. Provision of project management coaches for kickoff of a project, workshop, or lessons learned is a goal set for fulfillment by the end of the year.

Von Pattay said that because project management is not treated as a discipline, the role of project manager was often “dumped” on someone. “In the past, the industry’s project managers were lead engineers, and not specifically project managers. People did not understand that project management is a job in itself. If you are a project manager, you should not be the chief geologist.

“As a result, people who were great engineers, adept at organization, or had a clear picture of what a plan should look like were selected as project managers. Although they knew exactly how the plan was going to work, that did not mean that they could communicate it. Generally speaking, engineers may not be the group identified as the best communicators. You become an engineer because numbers are closer to you than lyrics.” With the tools, techniques, mentoring, and coaching made available to facilitate communication, the field widens for those interested in project management.

Morrison said the transition to project management as a discipline is yet to come. A dedicated training perspective is crucial for building the career paths of project managers, thus providing the potential for climbing the career ladder from junior to senior project manager to program manager.

For Further Reading

SPE 162076 Multiplying Project Success for Future Growth Through a Dedicated Project Management Support by P. von Pattay and Michael Morrison, Wintershall.

SPE 163729 Social Computing in an Exploration and Production Enterprise: Achieving Community Learning and Knowledge Transfer by C. Jenkins, T. Lowe, and Frederick Mjema, Devon Energy.

IPTC 16574 Knowledge Management in Engineering Activities of an Operating Company by G. DiLiddo, G. Gabetta, F. Ponti, et al., Eni E&P.