The words “UK North Sea” do not engender much more than cautious optimism these days when talking about oil and gas production, with dropping production and high decommissioning costs dominating the conversation.

The reality is more complicated. After 14 years straight of production declines, and particularly sharp production declines from 2010 to 2014, the UK continental shelf (UKCS) saw production increases from 2015 to 2017. While it is a mature basin in the midst of overall decline, the UKCS has shown potential. Production in recent years has been boosted by a number of large projects coming online such as BP’s Schiehallion and Chevron’s Rosebank. Future production numbers may see a boost from discoveries like BP’s Capercaillie and Achmelvich, and Hurricane Energy’s discoveries at Halifax and Lincoln in the West of Shetland area. Companies and government regulators also see opportunities.

Whether those opportunities will lead to anything beyond a temporary reprieve remains a question. Even if the decline resumes next year, as some have forecast, managing the assets still active in a way that avoids double-digit losses will be a challenge for all the stakeholders in the area.

The Value of Infrastructure

In discussing decommissioning and abandonment’s place in the North Sea conversation, Oil and Gas UK economics and market intelligence manager Adam Davey said he has seen little evidence of a massive pickup in activity, with more stories coming about operators trying to extend field life and defer decommissioning.

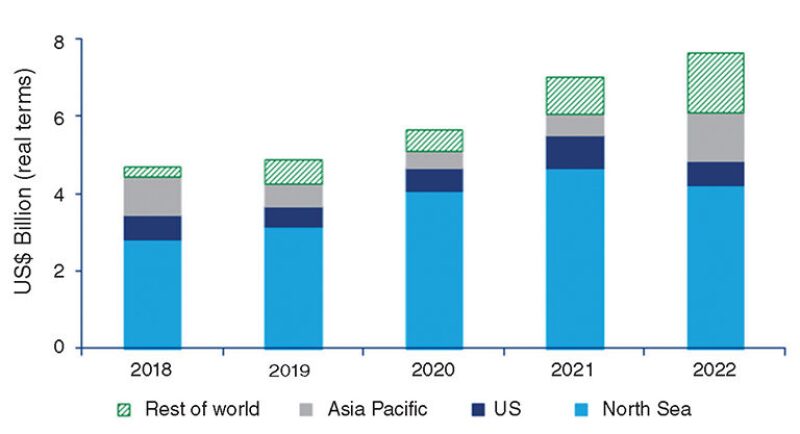

However, the massive cost of decommissioning is still the most pressing issue facing companies operating in the region. The North Sea makes up the majority of global offshore decommissioning costs, and while the region is forecast to comprise a smaller share of the global total over the next 4 years, the overall costs of North Sea decommissioning should still rise from 2018 to 2021 (Fig. 1). Wood Mackenzie predicted that decommissioning spend will overtake capital expenditure by 2022.

In the UK, decommissioning costs are expected to remain consistent at $2.3 to $2.7 billion annually over the next 5 years, compared to $532 million to $1 billion on the Norwegian continental shelf and $864 million to $1 billion on the Dutch continental shelf. Oil and Gas UK said it is an indication that there is no need to rush decommissioning efforts.

While decommissioning activity on the UKCS is much greater than in the other sectors on the North Sea, the consultancy said this reflects the total amount of infrastructure in the basin, as well as the fact that an increasing number of mature assets are naturally reaching the end of their productive lives. Wood Mackenzie said it is not necessarily an indicator that the UKCS is entering a steep decline.

Subsea tieback technology has long been a valuable resource for maximizing production in the region, and moving forward Davey said the Oil and Gas Authority (OGA), the UK’s regulatory body, is working on area plans to help protect infrastructure that may have significant tieback potential. This may include the adoption of a cost-sharing model where the operator of a valued decommissioned asset may not have to pay for much of the cost to keep that asset running.

“If [OGA] can identify particular key pieces of infrastructure that carry value greater than the production that goes through them—i.e., there’s a lot of tie-in prospects in the nearby area—they will work with the stakeholders to try and keep that piece of equipment running,” Davey said.

West of Shetland

The UKCS saw 12 new field startups in 2017, and Oil and Gas UK estimates four to six new field startups this year. These will be a mixture of floating production, storage, and offloading (FPSO) developments and subsea tiebacks. These startups will be among the largest in the region over the past decade.

One of the more interesting prospects in the North Sea is the West of Shetland field, one of the largest undeveloped oil fields in the UKCS. Located west of the Shetland Islands at the boundary of the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, the area has seen a slate of new discoveries over the past year that may help breathe life into UK production.

In May 2017 BP produced first oil from the redeveloped Schiehallion field. The field produced nearly 400 million bbl of oil since its initial startup in 1998, with peak production rates of 190,000 BOE/D. After 15 years of operation, BP suspended field production and decommissioned the FPSO. This was not an abandonment of the field: BP announced that it expected to unlock an additional 450 million bbl of oil and extend the life of the field to 2035 after the construction and installation of a new, purpose-built FPSO. The Glen Lyon arrived in Norway in April 2016 and took its permanent place in June of that year. Kevin Reynard, senior partner at PwC’s UK Oil and Gas Center of Excellence, said Schiehallion will help double BP’s UK North Sea production to 200,000 BOE/D.

BP is also planning to complete Clair Ridge, the second phase development of the Clair field, this year. The project involves the installation of two bridge-linked platforms, 26 producing wells, 10 water injection wells, and a tieback to the Clair Phase 1 export pipeline system located south of Clair Ridge. BP said it was targeting 640 million bbl of recoverable resources, and the facilities are designed to continue to produce until 2050, long after most existing North Sea fields will have been decommissioned.

Davey said BP’s activities in the region are just the tip of a potentially fortuitous iceberg. Oil and Gas UK estimates that Total’s Laggan and Tormore gas condensate fields figure to be among the biggest-producing fields in the UKCS over the next several years. The Chevron-operated Rosebank FPSO is expected to handle 100,000 B/D of crude oil, though the final investment decision is not anticipated until 2019 and first oil will likely happen in 2022. Davey also mentioned Hurricane’s Lancaster field and Siccar Point’s Cambo development as areas with potential.

“The West of Shetland is really exciting,” Davey said. “It’s the least developed, it’s very immature, there have only been something like 30 or 40 exploration wells ever drilled there. Compared to the rest of the UK it’s very lightly drilled, and we’ve had some big success there. There is no doubt that the proportion of production that comes from the West of Shetland is going to grow.”

Favoring the Supply Chain

While cautious optimism dominates the outlook of the UKCS and other parts of the North Sea, one area remains in a stagnant pattern: oilfield service companies. The supply chain is still focused on reducing costs, managing reasonable employment numbers, and integration through deals such as the Technip-FMC merger and the combination of Baker Hughes and GE Oil and Gas.

The UKCS has benefitted from the UK government’s response to industry concerns over economic policy that companies felt had created an obstacle to late-life asset transfer. Two years ago, the government lowered headline tax rates of profits related to production from 50–67.5%, depending on field age, to 40% across all fields.

The government also dropped the Petroleum Reserve Tax rate from 35% to 0 and the Supplementary Charge rate from 20 to 10%. Starting in November, HM Treasury will allow the tax histories of oil and gas fields to be transferred upon sale, allowing buyers to claim additional relief should the field need to be decommissioned. The government hopes this move will remove a major deterrent for new investors looking to buy assets in the North Sea.

“There’s been a limited history of collaboration between operators, but now the OGA is encouraging greater collaboration in an effort to reduce costs,” Reynard said. “We are seeing progress in this area. The government views the oil and gas industry as a helpful revenue-generation source for the national economy.”

These moves are expected to foster a more favorable fiscal regime, but service companies will still be under pressure to maintain financial diligence, he said.

“The oilfield service companies need to maintain their focus on keeping costs down and remaining competitive in an environment which saw a dramatic decline in oil prices and saw operators reducing their costs,” Reynard said. “Yes, the oil price is recovering, but service companies still need to remain competitive vis-à-vis costs through standardization and collaborating with operators.”

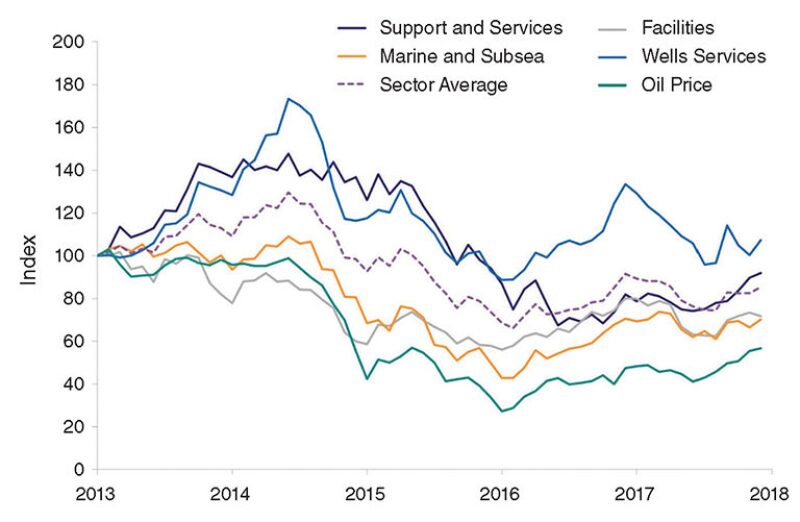

Oil and Gas UK forecast that supply chain companies will generate between $33 and $40 billion this year, which would mark the end of 3 consecutive years of decline, though that revenue spike will most likely come from the project development, maintenance, and subsea sectors. The agency expects oilfield services to make up the greatest share of price performance of any sector in the supply chain (Fig. 2). EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxation, depreciation, and amortization) fell by $2.3 billion on average from 2014 to 2016, a relatively modest amount that the agency said reflects the service company sector’s ability to adapt to a difficult environment. The average share price has recovered almost to pre-downturn levels.

Service Company Concerns

These numbers do not present the whole story, however. Free cash flow is still a concern. Oil and Gas UK said that service companies are dealing with longer payment terms imposed by their customers.

Supply chain companies that are most likely to survive the downturn are those that exported into new geographical areas, drove technological and digital innovation, merged with another company, or diversified into tangential industries.

Davey said that whether a company can accept lower margins with longer contracts depends on its business. Some supply chain companies have been willing to completely change their contracting models, taking on operational risk and delivery risk in a project in order to get higher margins if performance is strong. Other supplier service companies are not willing to do that because such a change in direction does not suit their investor mix or what the company is trying to achieve. Companies like that may move to other sectors, other geographies, and try to diversify from solely operating in UK oil and gas.

Diversification can be difficult for some service company subsectors because of the nature of services supplied—operators typically use local companies to provide most of their support services—but Davey said it is not impossible.

“A lot of those skills are transferrable,” Davey said. “At the end of the day, your core construction disciplines are required for that activity as much as they are for oil and gas. So, I think there’s a big focus as we move through the energy transition to make sure that some of the skills and competencies that we’ve developed as an oil and gas industry can be transferred to service the rest of the energy sector as and when it grows.”

In a January report released on the oilfield services industry, Ernst & Young (EY) examined UK service company performance vs. the Norwegian and Dutch sectors of the North Sea. While Norway has more service companies operating, the UK employs more staff, has a higher turnover, and saw a smaller turnover decline from 2015 to 2016, the last year of data included in the EY report.

The decline in the Norwegian service industry since the oil price downturn has been pronounced and has gone on longer than expected, with a 36% total revenue decline and a net job loss of 30,000 from 2014 to 2016, but the worst of the decline may be over. The EY report indicated a leveling of activity in 2017 and 2018, which may indicate increasing optimism as exploration and production (E&P) investments gradually go up. While a return to pre-downturn levels is not expected, EY predicts that oilfield services will remain the main value creator for Norwegian industry.

North Sea Acreage Awarded to 61 Firms in UK Licensing Round

Matt Zborowski, Technology Writer

Sixty-one companies ranging from supermajors to small, upstart independents were awarded 123 licenses over 229 blocks or partial blocks in the North Sea in the UK’s 30th Offshore Licensing Round in May.

The round, which primarily involved previously explored or mature areas, promises “to lead very quickly to activity, providing a welcome boost to exploration,” said the UK’s Oil and Gas Authority (OGA).

Shell led the way in overall licenses awarded with 12, seven of which it will operate. It committed to drill two wells and shoot 3D seismic. Equinor, formerly known as Statoil, took nine licenses spread across the UK shelf, eight as operator.

Other supermajors and big independents active in the round were BP with seven licenses, five as operator; Total with six operated licenses; Apache with four operated licenses; Eni with four licenses, half operated; Chevron with three operated licenses; and ConocoPhillips with two operated licenses. In May, ConocoPhillips was reported to be exploring the sale of its existing North Sea assets.

A number of UK-based independents also featured prominently in the round, including a pair of growing private-equity-backed firms. Zennor Petroleum gained the second-most licenses in the auction with 10, four of which it will operate. Chrysaor, which dramatically expanded its North Sea holdings last year with a $3-billion acquisition from Shell, gained six operated licenses and plans to drill its first well on the acreage next year.

Other UK independents taking five or more licenses were Cluff Natural Resources, Actis Oil & Gas, Nautical Petroleum, Parkmead Group, and Tangram Energy. Spirit Energy, the Oslo-based firm created through the merger of Centrica’s exploration and production unit and Bayerngas Norge, gained six licenses.

Quick Jolt to Exploration and Development?

The round included commitments to drill eight exploration or appraisal wells and shoot nine new 3D seismic surveys. Fourteen licenses involve immediate field development planning.

OGA said the newly awarded acreage may contain an estimated 320 million BOE from about a dozen previously stranded, undeveloped discoveries. Wood Mackenzie estimates the UK continental shelf (UKCS) has around 1.5 billion BOE in potentially commercial undeveloped discoveries, many of which were previously considered to be too small or technically challenging.

The UK last offered mature areas on the UKCS in the 28th Offshore Licensing Round in 2014, which was one of the country’s largest rounds ever. A total of 175 licenses were awarded just as the commodity price downturn was taking effect.

Set to launch this summer is UK’s 31st Round. It will focus on underexplored and frontier areas of the UKCS, covering the East Shetland Platform, North West Scotland, South West Britain, and the Mid North Sea High.

Ahead of the round, the UK has made available almost 19,000 km of newly acquired broadband seismic data, 23,000 km of reprocessed legacy seismic data and well data packages, and new geotechnical studies to investigate subsurface uncertainties in the areas.

The Role of Private Equity

North Sea investment has been historically dominated by major international oil companies (IOCs), but lately it has been focusing resources in other areas. Wood Mackenzie estimated that investment by the majors has fallen 60% from 2013 to 2017. In their place, private-equity (PE)-backed companies have entered the region with a desire to spend money. In a report released last August, Wood Mac estimated that there are around 20 PE-backed vehicles with a combined war chest of $15 billion for North Sea acquisitions.

The firm said that PE’s entrance into the North Sea has brought a different operational approach, with a focus on quicker project timelines. Davey echoed this sentiment. He said a lot of the PE activity in the region involves companies investing in assets with the intention of increasing their value and exiting with a decent profit multiple in a short timeframe (between 5 and 10 years) through cost reduction, improved efficiency, and increased output.

“There are things that need to be in place in order to add value to whatever you’re buying,” Davey said. “The No. 1 reason we’ve seen an increase in PE investment is the opportunistic side. A lot of it came when the oil price was very low, and some of it has come with oil at $50 a barrel. So there’s the thinking that they’ll be able to create some value by exiting when the price is higher. It’s safe to say that, whether it’s deepwater or anything, that principle applies.”

Last November Aberdeen-based Siccar Point Energy sold its 26% equity interest across three production licenses covering the Jackdaw discovery to Dyas UK. The company is also reportedly looking to sell up to half of its 20% working interest in Rosebank. It is planning to focus its resources on its core assets in West of Shetland. Last year, it signed a deal with Baker Hughes, a GE company, to help develop Cambo, a field in which it holds a 70% operating interest. Siccar Point said the field, located near Rosebank on the border of the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, holds more than 600 million bbl of oil in place. Siccar Point also spent $1 billion to acquire the OMV Group’s UK asset portfolio.

The US-based Carlyle announced in January its plans to raise an additional $2.5 billion to buy oil and gas assets outside of North America, with the North Sea being one area of focus. Carlyle, which has said it aims to raise $100 billion by 2020, provided equity funds along with CVC Capital Partner to help start Neptune Energy’s oil and gas arm. In January, Neptune announced the acquisition of Engie, one of the largest E&P businesses in the North Sea with proven and probable reserves of 672 million bbl. The deal included Engie’s operating stake in Gjøa, the field off the southwestern Norwegian coast that contains an estimated 40 billion m3 of gas reserves.

Another US group, EIG, was the primary backer of Chrysaor’s $3.8-billion acquisition of Shell’s North Sea assets.

Reynard said PE will continue to play a major role in the North Sea moving forward, and that firms may begin focusing more on service company plays.

“The banks’ involvement in funding the North Sea has become more challenging as they face pressure to reduce investments in carbon transactions, so there is greater opportunity for private equity and debt capital markets,” he said.

What the Future Holds

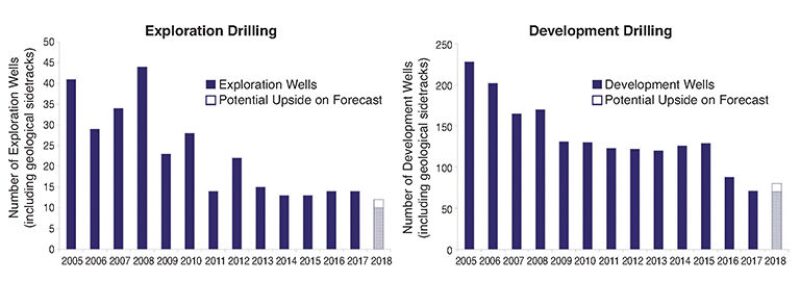

While the new discoveries have helped the region stave off a steep decline, all signs point to this uptick in activity being a temporary reprieve. The UKCS saw 14 exploration wells spudded last year. While this is in line with the 5-year average, it is still less than half the average of the number of exploration wells drilled from 2001 to 2010 (Fig. 3). Oil and Gas UK said industry will have to return to this previous rate to realize even the lower end of the remaining 3–9 billion BOE yet to be found. Development drilling has also fallen 45% in the past 2 years.

In addition, discovered volumes are well below the current UKCS annual production rate, which is approximately 600 million BOE. Even if all the reserves discovered in 2017 are developed, the region will still be producing more from existing fields at almost twice the rate that it is generating production from new fields. Exploration and appraisal has not kept pace with the progression of developments over the past decade, which means that the portfolio of economically viable development opportunities is shrinking each year.

So what is the best-case scenario for the region in the near future? Reynard said there may be a slight increase in production as certain development projects ramp up, and while long-term prospects are of a maturing basin in decline, the application of new technology, innovation, and collaboration will present new opportunities. Davey said to expect an increase in production ranging from 2 to 5% this year, with a possible similar increase in 2019. After that, though, he said the challenge will be the proper management of the production decline, restricting it to 3 to 5% per year and avoiding any years of double-digit production decline.

Oil and Gas UK said that E&P companies will focus on development drilling opportunities that provide the greatest return on investment, which may mean that only the most profitable wells will get drilled moving forward. Davey said successful exploration and development will play a significant role in finding the volumes that can mitigate the decline.

“If you had asked people 7 or 8 years ago that same thing, they’d have said no, but the reality is that the new projects that have come on stream have been sufficient to turn around the production decline. Whether that can happen again 7 or 8 years from now all depends on whether we’re successful with the exploration drilling and whether we can keep these critical pieces of infrastructure in place for long enough that companies are still looking to tie things in and bring more things on stream,” Davey said.