The deepwater US Gulf of Mexico (GOM) sector has struggled since the onset of the oil price downturn in 2014, but as costs settle and operators establish new standards for running efficient projects, this year may be a significant turning point for the industry in the region.

In January, Wood Mackenzie published a report predicting that production of oil and gas in the deepwater GOM will reach an all-time record high this year, with more than 1.9 million BOPD, surpassing the previous record set in 2009 by nearly 10% and representing 13% growth year over year.

William Turner, Wood Mackenzie’s senior research analyst and lead author of the report, Deepwater GoM: 5 Things to Look for in 2018, said that, more than 2 months into the calendar year, the level of activity in the region is still on track to meet expectations. However, recent developments may have an effect on that trajectory.

Policy Impacts

In January, the US Department of the Interior (DOI) announced a proposal to place more than 90% of federal offshore land containing oil and gas—including land in the GOM—up for auction between 2019 and 2024. In February the DOI’s Royalty Policy Committee issued a recommendation for lower royalty rates for offshore oil and gas drilling on seabed owned by the US government.

If approved, royalties from offshore drilling would drop from 18.75% to 12.5%, the lowest royalty rate permitted. The US Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) had already relaxed royalty rates to 12.5% for some shallow-water leases in August 2017.

With the WTI and Brent crude prices still hovering in the low $60s as of early March amidst relatively high supply, the recommendation could make it more attractive for operators to look at bidding for offshore oil leases in the GOM.

Turner said while the decision on the royalty came faster than anticipated, it is likely the US federal government wanted it in place before Lease Sale 250 on 21 March. At the time of this writing, it was scheduled to be the largest regionwide sale in US history, with 77.3 million acres offshore Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida available for exploration and development. The sale includes approximately 14,700 unleased blocks located in the GOM’s Western, Central, and Eastern planning areas. The BOEM estimated that these blocks contain about 90 billion bbl of undiscovered technically recoverable oil and 327 Tcf of undiscovered technically recoverable gas.

The royalty rate may have a bigger impact on operators’ decision making in the coming months. For instance, Turner said it is possible that Total may try to rebid for leases in the North Platte field—where it holds a 40% working interest—rather than taking over operation of its holdings from Cobalt International Energy.

“I was convinced that Total would not want that to go out into the open market, that they would get a drillship out there and extended that lease, and perhaps even take over operation of that lease so that they didn’t get it out on the open market,” Turner said. “But—and I don’t know what the answer is—is it a risk they’re willing to take to let it go out on the open market, rebid, and get it at the lower royalty rate, which could add a lot of value to that project?”

Exceeding Expectations

Turner said that the discovery size of the Ballymore and Whale prospects are expected to be much larger than previously thought. Shell said in January that the Whale deepwater well encountered more than 1,400 net ft of oil-bearing pay. Evaluation was still ongoing at the time of this writing, but Turner said it would not be surprising to see 10 times more barrels than initially expected.

Ballymore faces a similar issue. Chevron, which holds a 60% working interest in Ballymore (Total holds the other 40%), said it encountered more than 670 net ft of oil pay with excellent reservoir and fluid characteristics. Though the company had not disclosed totals by early March, Turner said it is possible that Ballymore could be a 400 million bbl discovery. While this is not a bad problem for an operator to face, Turner said a larger-than-expected discovery may force Chevron to make a difficult decision with regards to development. The company may need to refurbish its Blind Faith platform to handle the additional production from Ballymore, or it may choose to build a new platform altogether.

“Now they have to go to work either refurbing the Blind Faith platform or even getting another platform out there,” Turner said. “It’s almost a bit of a headache in that the size of the discovery was so big that they have to change their plans a little bit.”

Turner said either option will be capital-intensive. He said that Blind Faith has enough life left to service the current field, but its capacity would need to be increased to take on Ballymore. Because it sits just 4 nautical miles away from the discovery, Turner said he thinks it makes more sense for Chevron to repurpose the platform. Ballymore will present some technical challenges, though: it is an ultrahigh-temperature field with a lot of tar, which may affect the efficacy of downhole tools.

Majors vs. Independents

The economics of deepwater GOM still heavily favor larger operators with the appetite to invest the capital required to develop a megaproject. However, Turner said smaller companies backed by private equity still have growth potential in the region. In January, LLOG began development drilling at the Buckskin Project in Keathley Canyon. A drillship will drill the initial two wells to about 29,000 ft, after which subsea facilities will be installed. First oil is expected in mid-2019, and the field is estimated to contain about 5 billion bbl of oil in place.

Buckskin is one of several LLOG projects coming up that will utilize subsea tieback systems. Its Claiborne development will tie back to the Coelacanth platform operated by Walter Oil and Gas. The LaFemme/Blue Wing Olive and Red Zinger developments will be tied back to LLOG’s Delta House platform. Crown and Anchor will tie back to the Anadarko-operated Marlin facility. All five developments are scheduled to begin production sometime this year. First oil at Claiborne is expected in mid-2018, production at Crown and Anchor will begin sometime in the next few months, and the other three are expected to start up in the second half of the year.

Turner put LLOG at the top end of the small independents making waves in the GOM, but he said Fieldwood Energy may jump ahead of LLOG following its $710 million purchase of Noble’s deepwater GOM assets in mid-February. The transaction includes Noble’s interest in six producing fields (Galapagos, Swordfish, Gunflint, Dantzler, Big Bend, and Ticonderoga) and all undeveloped leases, which Noble estimates will produce slightly more than 20,000 BOED in 2018. The transaction took place on the same day Fieldwood filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy as part of a plan to cut its debt in half. Since Noble’s producing fields are already developed, they will not require Fieldwood to invest significant amounts of capital. Turner said the Field-Noble transaction should boost Fieldwood’s production by 28%.

“For a company the size of Fieldwood and a company the size of LLOG, they still have growth prospects in the Gulf of Mexico in the tiebacks—those are the 20-million, 50-million barrel tieback opportunities. The capex on those is, let’s say, $200 to $450 million. That’s meaningful growth for those companies,” Turner said.

As large and small companies find their footing in the GOM, the mid-sized operators—which Turner defined as companies producing 100,000 to 500,000 BOPD—are looking for or have already found their exit strategies. Freeport-McMoRan’s foray into deepwater GOM was a key factor in the company’s 66% share price collapse from 2013 to 2016, and in September 2016 the company sold its assets in the area to Anadarko. Selling its GOM assets to Fieldwood will allow Noble to focus on its more profitable US onshore shale developments, as well as its holdings in the eastern Mediterranean. In a statement, Noble Chairman David L. Stover called the Fieldwood deal “the last major step in our portfolio transformation.”

Following the announcement of the sale, Noble’s price on the New York Stock Exchange jumped from $26.28 on 16 February to $29.12 on 20 February, a 10.8% difference. Turner called this a “clear indication” that the company’s investors are more bullish on shale than on deepwater GOM.

“Wall Street seems to be undervaluing deepwater Gulf of Mexico investment, but for the folks like LLOG and Fieldwood that are backed by private equity, they clearly have a different view than Wall Street,” Turner said.

Looking Ahead: Short-Term Peak?

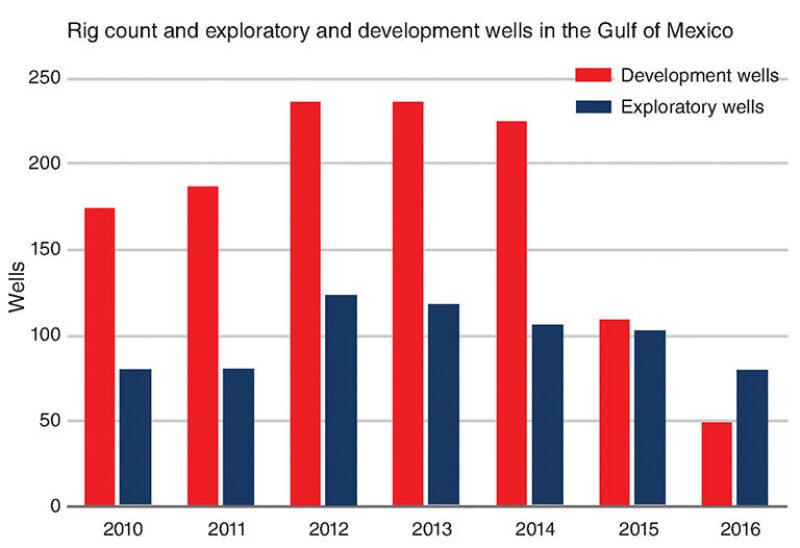

Despite the growth in production, the consultancy expects exploration activity to remain flat as operators continue to focus on conservative tiebacks that are typically lower-volume, lower-impact discoveries. Turner said that conventional deepwater fields cannot sustain current GOM production growth, and that increased investment in exploration and development, particularly in ultrahigh-pressure/high-temperature projects, will be critical to maintaining production levels in the near future. Without that, production levels may plateau after 2019.

Recent large discoveries may provide relief sooner rather than later. Turner said Shell may potentially fast-track Whale, possibly bringing it online in 6 years. Doing that would likely require the company to duplicate its efforts with Vito, in which a lot of contracting has been agreed upon prior to sanction. If this happens, Whale could spearhead another period of growth. Until then, however, GOM production will have to sustain itself on smaller volumes.

“That period between 2019 and 2023 is going to have be sustained—I’ll call it a bit of a plateau, maybe—with subsea tiebacks and maybe production from projects like Buckskin,” Turner said. “But until the really large volumes start coming back to the Gulf of Mexico, we may see 2019 as sort of a short-term peak.”