The oil and gas industry is technical and challenging. Because the technical issues are dealt with by humans, we also face social, psychological, and cognitive issues which are frequently as challenging. In this regular column, we address the softer side of engineering. Decision theory will be one of the recurring themes of the column.

Thousands of books and innumerable magazine articles have been written about decision making. In the majority of them, the subject is how to choose the best from among alternatives based on decision criteria or objectives. In real life decisions, the alternatives and objectives are not usually specified. In a real decision, we usually must set the objectives and identify the alternatives. Little is written about how to do that. An exception is Ralph Keeney’s work on value-focused thinking.

I read Keeney’s book, Value-Focused Thinking, about a decade ago and have been a fan ever since. His insights have changed the way I approach decision making. I’m excited to have him share his insights with you in this column.

—Howard Duhon, GATE, Oil and Gas Facilities Editorial Board

Why bother to make decisions? Decisions produce worry and anxiety as well as expose any lack of information or knowledge. Decisions require time and effort. You might regret your choice. Why not just avoid making decisions? Responses such as “you have to make decisions” don’t recognize the opportunity that decisions offer. The only way that leaders and engineers in the oil and gas industry can have a purposeful influence on anything is through their decisions. Without decisions, one must simply follow a path through life laid out by others and caused by circumstances beyond your control.

Most of us do not simply want influence; rather, we want specific influence to make something better or as good as it can be. This requires a clear understanding of the values that are the basis for what defines “better” in any specific situation. Values indicate why we care about making a decision and focus our efforts on achieving our purpose.

Standard approaches to help decision makers do not begin with values. Rather, once a decision problem has been recognized, decision makers begin by identifying alternatives that will solve it. After a candidate alternative, or perhaps a set of alternative options, has been identified, only then do decision makers implicitly introduce their values by contemplating the pros and cons of the alternative. These standard decision-making approaches involve what I refer to as alternative-focused thinking. It is backward because it tries to solve a problem with an alternative before clearly understanding what one hopes to achieve by solving it.

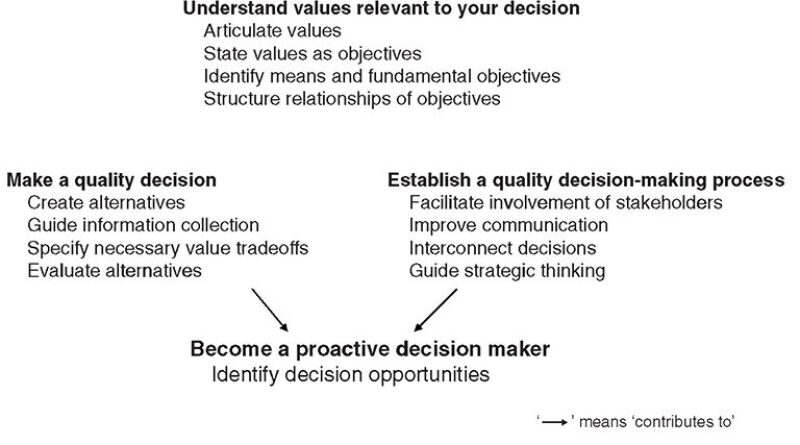

The alternative approach for thinking about decisions is value-focused thinking. With value-focused thinking, the initial thinking in any decision situation is about values, meaning anything that you really care about in this decision situation. Identifying and understanding the full set of values relevant to any major decision form the basis for conducting all aspects of a quality decision process and for informed decision making. Fig. 1 lists the aspects of the value-focused decision-making process.

Understanding the Values Relevant to Your Decision

Any major decision problem has many relevant important values. If an oil pipeline is desired from Location A to Location B, high-level values would include economic costs, environmental effects, socioeconomic effects, health and safety, and accidents. Each of these values could have numerous components. Some specific environmental values include the effects on water quality and effects on plants and animals and their habitats. Health and safety values would be categorized by whether they affect workers or the public; occur during construction or during subsequent operations; and carry risks for injury, illness, or death.

Clarity about the meaning and specific relevance of each value is important. This is achieved in two steps: (1) converting each value to an objective and (2) organizing the objectives into means and fundamental objectives and specifying their relationships.

A fundamental objective is something that is important to you in and of itself, such as life and health. A means objective is important only if it helps you achieve one of your fundamental objectives.

To clarify the meanings of any value and to place all values in a common format, each value can be represented as an objective using a verb and an object. As examples, an objective for the value “water quality of an aquifer” might be “avoid pollution of the aquifer.” Specific objectives concerning socioeconomic effects might be “provide jobs in specific regions” and “minimize disruption of communities.” The objectives that specify concerns about accidents might include “follow authorized safety procedures, ensure quality construction, and minimize future operations accidents.” Following authorized safety procedures is a means to ensure quality construction, which is a means to minimize operations accidents. Minimizing operations accidents is also a means objective that may influence fundamental objectives such as “minimize loss of life” and “avoid environmental damage,” as well as the means objective of “maximize uptime of the pipeline,” which itself is a means to “minimize repair costs” and “maximize revenue.” Objectives concerning the loss of life, environmental damage, costs, and revenue are some of the fundamental objectives for a pipeline decision. Means objectives are important for their effects on the achievement of the fundamental objectives. The fundamental objectives are those relevant to directly evaluate alternatives. It is important to recognize that means objectives should not be included in the evaluation along with the fundamental objectives because this would constitute double counting.

Identifying relevant values for a decision is not a simple task. If more than one individual is involved in the decision process, each should separately provide relevant values. The combination of each individual’s recognized values will create a more complete set of values than any individual set. When a group collective tries to develop values, members tend to anchor on one another’s thoughts in the discussion, and the range of values provided is narrower.

Values cannot be articulated by only asking individuals to write down their values for an important decision. Research has shown that people typically list only half of the relevant values on decisions that are important to them or their organizations and the importance to them of the values that they fail to identify is of the same magnitude as those that they initially recognize.

To help an individual create a more complete set of values, a process of interrelated steps can stimulate deeper thought about what one cares about in a decision. Step 1 is to create a wish list of everything that one hopes to achieve by facing a particular decision. When you think you are done with such a list, which often occurs in less than 15 minutes, you definitely are not done.

Step 2 is to challenge yourself and double the number of values on your list by thinking more broadly and more deeply. This doubling can be done if you take this challenge seriously.

Step 3 is to stimulate additional values by using each of several relevant components of decisions (alternatives, consequences, goals, constraints, strategic values, and generic values). Consider an alternative, real or hypothetical, and then ask yourself what is good or bad about it. Each response might uncover a previously unrecognized value relevant to your decision problem. Thinking about the consequences of your eventual choice also suggests important values. Goals and constraints are a particular type of statement of relevant values. Strategic values and concepts mentioned in mission or vision statements offer important clues to values. Examples such as “employees are our greatest asset,” “customers are the boss,” “provide shareholders with superior returns,” “diversity,” or “teamwork” may suggest more specific values relevant to any decision. Generic values are essentially categories, such as those listed earlier (economics, socioeconomics, environmental effects, health and safety, accidents) that also can be probed in deeper detail for values relevant to a specific decision.

In Step 4, separately for each of the values already identified, ask yourself, “Why do I care about this value, what do I mean by it, and is this part of a more general value?” This process helps

uncover and suggest more potential values and helps recognize dependencies among them.

This process can be somewhat tedious and challenging for an individual to conduct on his or her own. It typically goes more smoothly and is much more interesting and illuminating and yields better results when it is facilitated by someone experienced in using the process. One method, therefore, is to involve an interviewing analyst, whose job it is to help search through the individual decision maker’s mind in a one-on-one discussion to ask probing questions and get all of the relevant values written down and organized. Once the values are organized, they can be reviewed by the individual for any appropriate modifications. Typically, the submitted result that identifies all values as objectives and relates all the means objectives to the fundamental objectives gives the individual the feeling that they now understand their decision problem much better than before.

This process works particularly well when there are multiple parties whose values are relevant to a decision. These parties may be in different departments of an organization or they may include external stakeholders such as communities or states influenced by the potential alternatives, environmental groups, and partner organizations. Values are gathered from each relevant party as described and then are combined. This process naturally generates some objectives that compete with each other, but that is the nature of any complex decision. Once inferior decision alternatives are eliminated, one can almost always achieve better performance on one objective by accepting less performance on another. A specific example is that you can always pay more to make something safer or better, so value tradeoffs must be made when making decisions.

Make a Quality Decision

The best alternative that can be chosen in any decision can obviously be no better than the best alternative being considered. So, if you use a process that can create just one alternative that is better than the previous best alternative, the contribution is significant. Because the reason for considering alternatives is to achieve one’s objectives, using those objectives to stimulate more thought about possible alternatives is fruitful. For each of the listed means and fundamental objectives, ask separately what one could do that would improve performance on that single objective. Collectively, the responses to all these questions will provide useful information to create new alternatives or improve existing alternatives.

For some decisions, a great deal of time and money is spent collecting information, some of which turns out to be of little or no use. To help avoid such unanticipated circumstances, the set of fundamental objectives for a decision characterizes all the information that could be useful. It is not useful to collect information that does not help indicate how well each of the alternatives measures up in terms of achieving those fundamental objectives. If the objectives are prioritized, the information of most relevance helps describe effects in terms of the higher priority objectives. Such information may lead to a conclusion that some alternatives are definitely inferior, so no more information need be collected for those. This could save both money and valuable time.

Setting logically sound priorities among objectives requires the decision makers to explicitly make value tradeoffs about the relative value of specified amounts of achievement on one objective vs. specified amounts of achievement on another objective. These value tradeoffs help address difficult but unavoidable issues such as, “Is it worth USD 30 million to reduce the likelihood of a particular offshore platform failure from 2 in 1,000 to 1 in 1,000 annually?”

A consistent set of value tradeoffs, together with a description of how each alternative measures up in terms of each objective, provides the basis for evaluating alternatives. With this information, one can proceed with a qualitative but systematic evaluation or construct a quantitative model to assist in evaluating the alternatives. An advantage of a quantitative model is that it allows one to perform sensitivity analyses and answer numerous “what if” questions relatively easily and quickly. In any case, it should be recognized that a quantitative analysis provides insights for making the decision; it does not make a decision. Only people, using information and insights from thinking and analysis, can make decisions.

Guiding a Quality Decision‑Making Process

Numerous major decisions in organizations in the oil and gas industry encounter setbacks because the interests of certain stakeholders were not accounted for adequately or they did not appear to be accounted for in the decision-making process. Why do these stakeholders care? Analogous to the case with decision makers, they care because of their values. Hence, a natural and appropriate place to include their interests is in articulating values relevant to the decision. If environmental or community stakeholders care about potential degradation of an aquifer near a proposed pipeline route, have them articulate their concerns and ideas to avoid or minimize the problem. If commercial fishermen in a region are concerned about possible damage to a fishery that might result from offshore development, obtain their values and understand their concerns. The intent is to eventually make a decision that is better for all relevant parties and, in

doing so, avoid long expensive delays or foiled projects.

Communication with all relevant parties—stakeholders, regulatory authorities, shareholders, and the public—can be much easier if you know the values of each. Then your communication can be focused to address their concerns. For a major decision in an organization, financial, engineering, public relations, regulatory, and legal departments may be involved and have particular concerns different from each other. Each of these concerns should be articulated as values and appropriately considered in any decision-making process. This promotes teamwork, enhances collective understanding, and saves time in addition to allowing better decisions to emerge.

Many major decisions in an organization will tend to have similar high-level objectives. The economics and health and safety concerns will often be the same in many major decisions. The details of environmental and social concerns will likely differ but be similar in relevance in various decisions. The value tradeoffs represent organizational values and can be consistently used across various decisions.

The fact that many values are common for organizational decisions suggests the usefulness of clearly understanding the strategic values of the organization. These essentially specify what the organization wishes to achieve by being in business. These values should remain quite stable over time and provide a basis to identify more specific values for any decision worthy of thought being contemplated by the organization. In this way, specifying their strategic values offers the top management a common-sense and logical way to guide all decisions made within the organization and to empower all employees so they can make decisions consistent with company values.

Becoming a Proactive Decision Maker

Who should be making your decisions? Clearly, you should. So who should be controlling the decisions that you face? Obviously, you should; but, what does this operationally mean? Decisions will occur beyond your control that you will have to deal with by making related decisions. Naturally, these will be reactive decisions because they address problems that have already occurred.

To be proactive, you must create your own decision problems and set out to address them. I prefer to think of these as decision opportunities rather than decision problems. Because the only way for you to purposefully influence anything is by your decisions, you must recognize useful opportunities and make the decision to address them. A logical basis for creating decision opportunities is to use your values. Decision opportunities may be created from the organization’s strategic values or from more specific values related to specific concerns. Thinking about your values, you might define a decision opportunity to make offshore facilities safe from terrorist attacks, to lower the political risks of your organization’s oil supply, or to enhance the quality and timing of information relevant to critical decisions that is available to executive officers.

Choosing to create and address decision opportunities might put you in a position where some undesirable decision problems do not occur in the future. This is best illustrated by an analogy. If an unfit and unhealthy individual recognizes the decision opportunity to improve fitness and health, he or she will have to make decisions about exercise and eating and perhaps about drinking and smoking. These may be tough decisions, but they are a lot more appealing than a future decision problem of where to get a triple bypass next week or, worse yet, forced decisions by others about handling the deceased person’s estate.