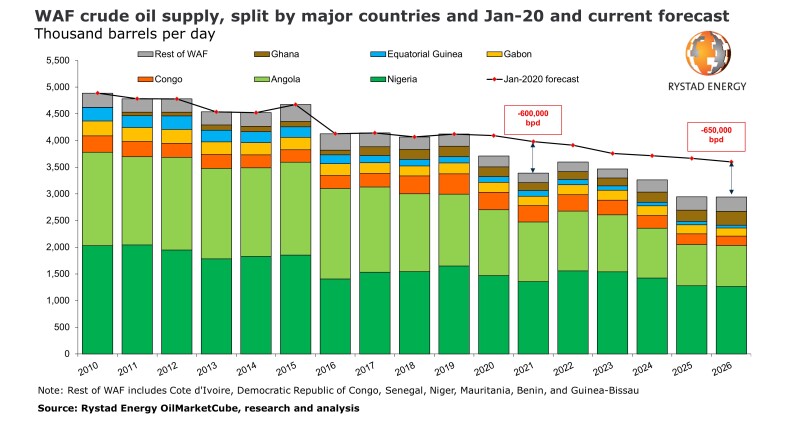

As global oil production comes back from last year’s COVID-19 crash, West Africa’s production continues to fall. Daily oil production output in the oil-rich region has dropped from 4.12 million B/D in 2019 to 3.71 million B/D last year to the current 3.39 million B/D, according to a report from Rystad, which does not see a comeback ahead.

“The structural upstream obstacles that West Africa faces are realities that are not going away in the short term,” said Nishant Bhushan, upstream analyst at Rystad Energy.

The reasons for this range from continued weak demand for jet fuel to underinvestment in its fields.

“Even if jet fuel makes a spectacular recovery and demand for light and medium sweet crude grades returns, Nigeria and Angola, as well as other neighbors in structural upstream decline, will not be in a position to supply the market.”

The past 2 years are part of a long-term production decline dating back to 2010. The two biggest producers in the region, Angola and Nigeria, experienced the largest part of the decline last year.

Before the pandemic, the energy data and consulting firm said things were looking up for West Africa. “The region was in line for more investment and activity. Last year’s low oil prices and the unstable market conditions that have continued into 2021 changed the outlook, however, as major operators decided to practice capital discipline and limit their investment exposure in regions including West Africa,” the report said.

The big production variable is oilfield investment to address “rapid declines at mature fields due to a lack of infill drilling, postponement of final investment decisions that were originally planned for 2020 and 2021, a lack of investment in oil and pipeline infrastructure which leads to frequent production shut-ins (prevalent in Nigeria), and civil unrest caused by militia groups.”

Based on Rystad’s estimate, the region is producing well below its OPEC+ quota of 4.2 million B/D set in May 2020. The organization is feeling pressure for greater increases in its production quotas, which it again ignored during its ministerial meeting on 4 November. The quotas set in the monthly meetings are of little concern to West African members of the group because, Rystad projects, their total production will remain below 4 million B/D through 2026.

On the plus side, Nigeria’s production is expected to rise by 65,000–75,000 B/D over the next 2 years due to some marginal fields coming on line and expansions in some others. After that, Rystad said declines are expected to resume.

In Angola it expects production of high-quality light, sweet oil to drop by 300,000 B/D, a 30% decline from this year. The trend is the same for lower-production countries. Equatorial Guinea’s output is down 60% since 2010 and Gabon’s is off 30%.

For Africa’s largest energy producer, pushing up oil and gas production is a priority. With its recently enacted Petroleum Industry Act overhauling oil regulation, taxation, and royalty rules, Nigeria hopes to spur investment that will push its production up significantly. For example, the percentage paid on royalties is reduced on lower-production fields and also is reduced at lower oil prices, according to a summary from the accounting firm EY.

"The intent [of the Act] is to really transform the industry for us to be able to attract the required investment into oil and gas," explained Adewale Ajayi, a partner at KPMG in Lagos.

At the same time, the president of Nigeria, who is attending the COP26 meeting in Glasgow, was among the leaders of energy-exporting countries exporters promising net-zero emissions by 2060. That promise came with a qualification—to reach that goal, Nigeria needs “adequate and sustained technical and financial support,” CNN reported.

Meeting that pledge will require a total economic transformation. The recent International Energy Agency report showed the economies of Nigeria and Angola are as dependent on oil as Saudi Arabia and Iraq.

Pressure to drastically reduce carbon emissions is changing the ways of the major oil companies such as Total, Shell, BP, ExxonMobil, and Chevron that have long played a dominant role in the offshore oil fields that made West Africa a major oil exporter. They are all facing pressure from investors to reduce investment in oil and gas.

The incentive to develop the high-quality crude off West Africa has also been reduced by the surge of light crude from US shale plays. Oil exports from Nigeria and Angola to the US have dropped by more than 90% since 2010 due to the flood of lower-cost ultralight oil from US shale plays, according to data from the US Energy Information Administration.