When consulting, Quentin Fisher knows that it is often necessary to make million-dollar drilling decisions without the rock data needed to provide a definitive answer.

“During consultancy projects, I’ve also found that companies need to interpret production tests and make decisions, such as whether to abandon a well, drill a side track, etc. But they don’t have petrophysical property data to back up their decisions,” said Fisher, a professor at the University of Leeds in the UK.

The problem is that the required special core analysis is expensive and can take months, or even years, if the sample is from a tight gas field, where margins for economic success are often very slim. At the University “we were getting so much data we couldn’t handle it any longer,” which led to a long-term quest to create a computerized system to speed the search for other sources of data to fill in those gaps.

Fisher is the principal researcher on an 8-year-old project called PETGAS (Petrophysics of Tight Gas Sandstone Reservoirs), which aims to generate high-quality databases of the petrophysical properties of tight gas sandstones as well as computer software that helps identify features in the microstructure that are accurate indicators of hard-to-measure petrophysical properties.

It is a digital system that systemically seeks out data that experts in the field would have learned from long experience. “When you have been looking at these things for 20 years and have a massive amount of experience, you can look at the microstructure of samples and provide a reasonable estimate of key rock properties,” he said.

But the supply of such experienced eyes falls far short of the needs of the industry, which is increasingly focused on developing tight gas reservoirs in places such as Oman. High-volume drilling in low-permeability rock magnifies the risk that the well will never produce enough to justify the effort. Depressed global gas prices magnify the problem.

Oman is on Fisher’s mind because the joint industry project has added Petroleum Development Oman (PDO), the national oil company that is developing the huge tight gas resources there, as is BP, which was an early backer of PETGAS.

The project has not only created a computerized reservoir consultant, but as the project enters its third stage, it has created a set of tools to help appraisal teams seek out realistic petrophysical property analogs for reservoirs where laboratory measurements are not available.

These include:

- Software designed to quickly handle extremely large volumes of data in different formats, called the PETMiner, allowing users to quickly create displays to see if there is a correlation between data

- Extensive rock testing data based on cores from member companies, which include BG, Shell, and three European independents

- State-of-the-art testing equipment, including a unique mercury injection, which is capable of measuring capillary pressures at extremely high confining pressures (~650 MPa)

Details of the work done with data offer an inkling of the power of an experienced brain to sift through huge amounts of information in order to spot an analogous pattern.

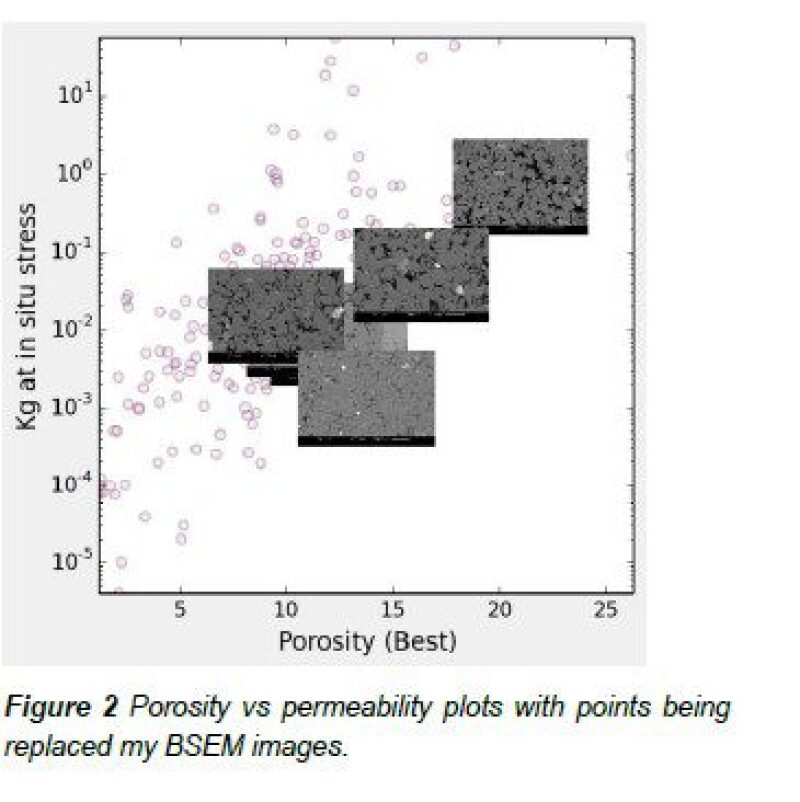

PETMiner data was initially sorted using Excel, but the rapidly rising volume of data forced a move to the use of Spotfire, a spreadsheet that can handle far more data. But even that fell short so PETGAS created a custom program. In addition to volume, it must be able to handle different formats of data to create displays that use data charts and images of the rock fabric obtained with electron microscopes and CT (computed tomography) scanners.

The group is currently developing a machine learning module for the software to recognize similarities in images, speeding the search for rock data likely to represent the reservoir in question. Often the goal is to identify a property that can be measured over a wide area based on a well log.

Exploration teams in the member companies are now able to use the tools the project has created, as are students at the University of Leeds.

A student “with a few hours of training created a really good rock classification system,” Fisher said, adding, “he came last week (to the University), and we have already got really good results.”