Editor’s Note: This is the first of a three-part series focusing on the contraction of the North American shale sector. Read Part II here.

Judgment day has arrived for companies of the oil shale boom and many are looking superfluous.

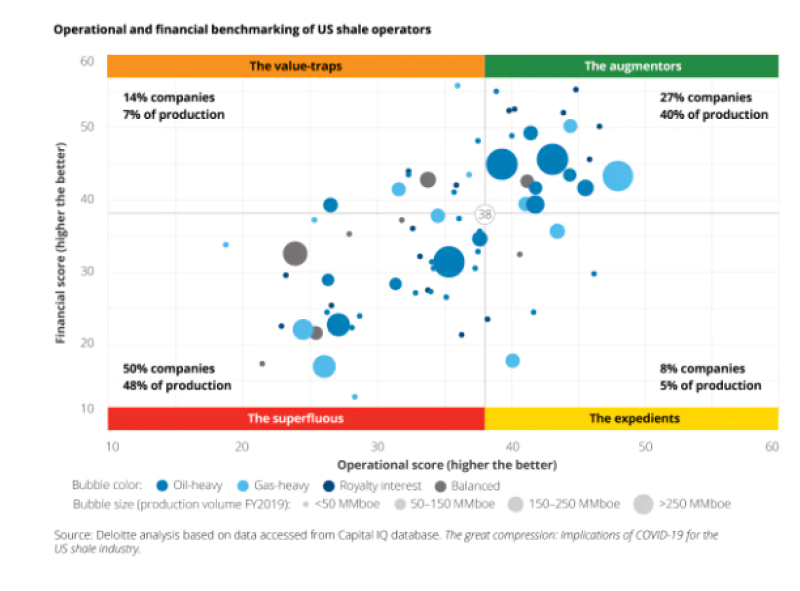

That is label used by Deloitte to describe 50% of the companies in its shale universe, representing nearly half the production.

The dictionary defines superfluous as more than is needed or wanted. The accounting firm describes them as “companies with a high-risk profile, making them unnecessary bets in the current environment.”

During the current deep funk in the oil business, these companies with low grades for financial strength and operational efficiency are in jeopardy.

“The grim financial position of many companies and weak economic outlook could trigger deep consolidation in the US shale industry,” Deloitte wrote in a recent report.

Note the use of the qualifier “could” in that sentence.

Half the companies in the shale business are considered superfluous because of weak financial and operational ratings, according to Deloitte. Source: Deloitte report

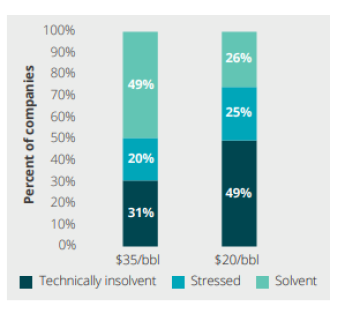

The accounting firm’s data deliver a clear warning—if oil prices remain around $35/bbl more than half the companies in the shale business are either technically insolvent or financially stressed. The pace of change will depend on how long those weak players can continue making payroll and paying the bills.

Bankers will play a critical role in the process based on their semiannual evaluations of how large a reserve-based loan an oil company can handle. Companies secure these loans with assets such as reserves (PV10) but the process also considers other debts owed, likely future oil prices, and other factors which may affect the company’s ability to repay the debt.

Those

reviews got tougher in April after the oil market crash inspired some deeply negative thinking. Based on past crashes, however, don’t expect a rapid response by bankers, whose options all come with significant downsides.

The simplest exit strategy is to force the borrower to sell its assets, but in the current market that is likely to yield dimes per dollar owed. Takeovers and mergers are not happening now in the oil business. And bankers are not in the business of trading stock for debt or repossessing oil assets and managing companies long term.

It is better to offer a stern warning and put off any action and hoping that oil prices and improved management will fix things.

In the industry, people call it “lend, extend, and pretend,” said Scott Sanderson, a partner of Deloitte. While he said the accounting firm’s analysis makes a strong case for consolidation, that hasn’t happened during previous downturns.

He said it is a fashionable argument to say this downturn is different. But so far there have been almost no acquisitions, and the number of bankruptcy filings is low considering the brutal state of oil markets.

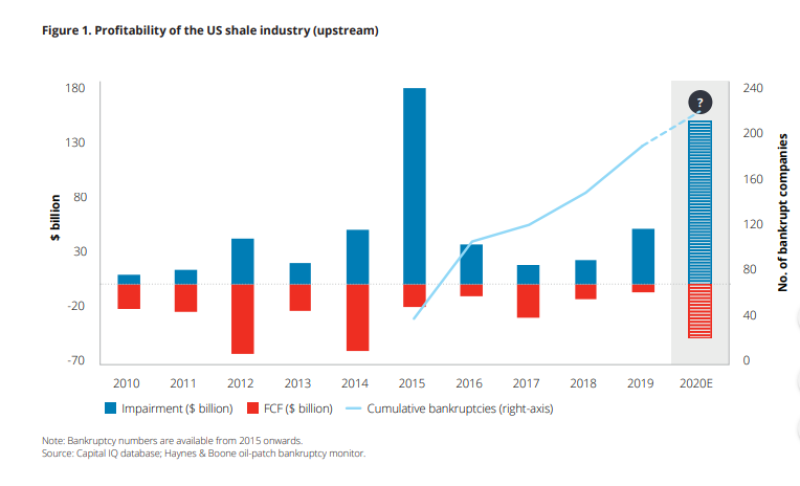

During the first half of the year 18 oil companies filed for bankruptcy protection, which is well behind the pace in 2016, when 70 cases were filed, according to the Oil Patch Bankruptcy Monitor compiled by Haynes and Boone.

But the pessimistic outlook of those who responded to other surveys by the law firm suggest the weeding out process has quietly begun.

Early Results

The outlook for the oil business changed in a day in March. Do not look for a rush to file for bankruptcy.

The peak in bankruptcies after the 2014 price crash was in 2016. The lag this time could be shorter. The recent filing by Chesapeake helped double the value of the money owed by companies that filed during the first half of 2020 to more than $20 billion.

Haynes and Boone said, “It is reasonable to expect that a substantial number of producers will continue to seek protection from creditors in bankruptcy.” And that will include some big names.

Charlie Beckham, a Haynes and Boone bankruptcy partner, predicted, “There are some big fish headed for the spillways.”

Big companies like Chesapeake will get the attention, but there are also a lot of small fish out there that could be forced to file by the time of their next big payment due.

One thing that is different about this crash compared to the last one is creditors are not as willing to negotiate deals to reduce debts with everybody.

One of those companies was Templar Energy, which was sold at a bankruptcy hearing in mid-July.

The Chapter 11 case was filed on 1 June in Delaware, but a declaration of facts from its Chief Executive Officer Brian Simmons described how its debt crisis began a year ago when the value of assets it put up to secure a bank loan was cut to less than what it owed, which ultimately led to a deal with creditors to sell off all its assets.

This spring, many shale companies likely got similar notices as lenders expecting oil prices to remain lower for much longer cut the value of assets, according to the Haynes & Boone survey.

During the last downturn, Templar was one of many shale companies that cut a deal with lenders. Templar reduced its debt by $1.4 billion in 2016.

“There was a wave of Chapter 11 filings following the last downturn and most of them ended up restructuring, often relaunching with the same management team,” said Andrew Dittmar, senior mergers and acquisitions analyst with Enverus. This time “some of the creditors appear to be a bit more skeptical on recapitalizing these guys and turning them loose,” he said.

Tough Options

Templar’s creditors are so skeptical of its ability to become a successful operator, they pushed for a sale that recently generated 20 cents per dollar owed.

Not an attractive outcome, but the alternatives require committing money and time to turning around a company whose value has been sinking for years. It is not alone.

“Recent filings especially appear to be resulting in more proposed 363 sales,” said Dittmar, referring to the section of the bankruptcy code covering asset sales to settle debt claims.

“The rise in proposed sales may indicate fewer debtholders are willing to work a restructuring deal to take equity and would prefer an exit, even if that involves a sale into a challenging market,” he said.

Templar is one of three private-equity-backed companies involved in bankruptcy sales, along with Gavilan Resources (in partnership with Blackstone)and Sable Permian Resources–The Energy and Minerals Group.

Oil shale companies have been a black hole for cash for investors whose money allowed shale producers to massively increase production. But many of those borrowers never generated sufficient cash flow to drill the wells needed to sustain that production, much less reward investors.

Over the past decade, negative cash flow in the companies tracked by Deloitte totaled $300 billion, resulting in $450 billion worth of impairments—writedowns of investments and loans—and nearly 200 bankruptcies.

The relationship between big investors and shale producers has broken down, based on anonymous comments in a recent survey of industry experts by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

“Access to capital and our bank group's willingness to extend our access to credit in our reserve-based loan remains our greatest risk and challenge,” said one, adding that his company was a financially strong, low-cost producer.

Another simply asked: “Is oil and gas private equity over?”

The “Great Compression” described by Deloitte certainly looks possible, though it will take some time.

A looming question is what will happen to the wells. In the past, there was a market for bargain-priced producing wells. But buyers need to consider that companies in the extraneous category also get low grades for operational skills such as drilling, fracturing, and producing those wells. And more wells will be needed to sustain that production.

“They are scared off by the constant churn of capital required to maintain production,” Sanderson said.