For millennia, Zoroastrian fire worshippers traveled on pilgrimage to pray at temples built where methane seeping from deep underground caused flames to burst from the earth on the Absheron Peninsula near Baku, the capital of today’s Azerbaijan.

The Venetian merchant Marco Polo observed such mysterious fires and puddles of oil that bubbled or even gushed as fountains to the surface as he trekked along the Silk Road through the Caucasus Mountains in the 13th century.

In a travelogue written in 1298, The Travels of Marco Polo, he is said to have described: “Near the Georgian border there is a spring from which gushes a stream of oil in such abundance that a hundred ships may load here at once. This oil is not good to eat, but it is good for burning and as a salve for men and camels affected with itch or scab.”

He was referring to the Khanates of Azerbaijan, a part of the Persian Empire in Marco Polo’s time but absorbed in 1806 into the Russian Empire whose czars took an interest in financing early oil production—hand dug and exported on camel back. Its high paraffin content was valued for producing kerosene lamp oil and lubricants including cannon grease.

World’s First Mechanically Drilled Oil Well

As the Industrial Revolution swept from West to East in the mid-19th century, many of the innovations and business systems around which the modern oil and gas industry were soon to coalesce were tested in the ancient “Land of Fire.”

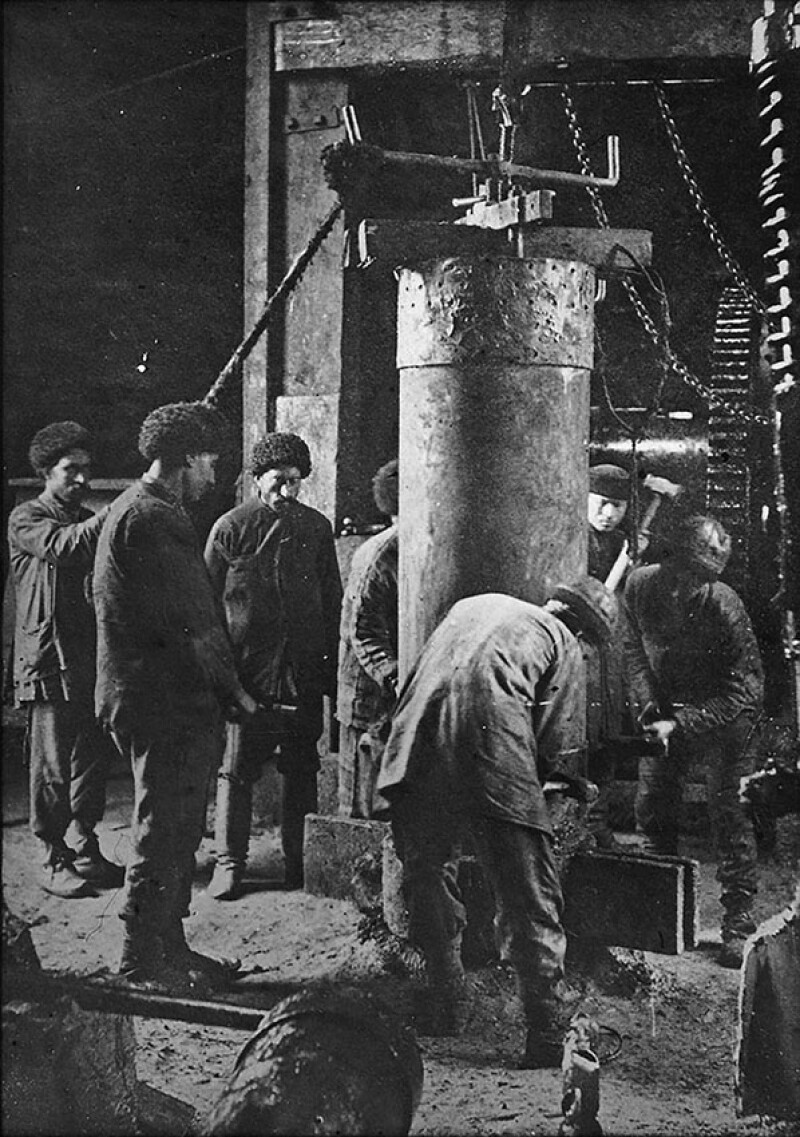

Czar Nicholas I (1825–1855) financed the world’s first mechanically drilled oil well in 1846 using a cable-tool percussion drilling method. A 21-m-deep (69 ft) exploration well was the result.

This happened a decade before Edwin Drake added steam-engine power to a mechanical drill to put Titusville, Pennsylvania, on the map in 1859, as described in the Branobel History archives.

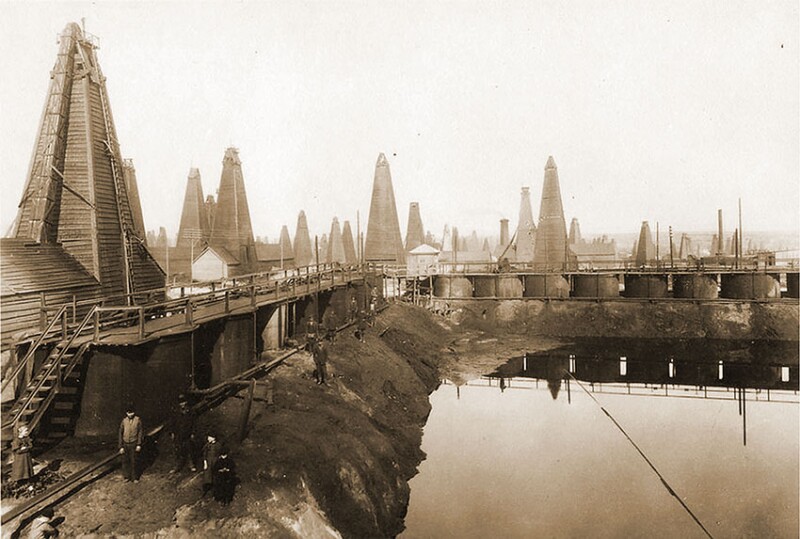

By 1871, with Nicholas’ son, the reformer Alexander II now on the Russian throne, boreholes had replaced buckets across the Bibi-Heybat and Balakhani oil fields.

The arrival from Sweden in the 1870s of Alfred Nobel’s brothers, Ludvig and Robert, brought a step change to Azerbaijan in terms of industrial innovation, construction, and logistics such that by 1900 Azerbaijan was producing 50% of the world’s oil, historical sources agree.

Alexander II had abolished the state monopoly on oil production in 1869, opening the door to foreign industrialists and their capital.

Robert Nobel obliged and opened the joint stock Branobel Co. in 1878 with a partner from a weapons plant in the Russian town of Izhevsk. He put down share capital of 3 million rubles ($30,000 in today’s money) to register Tovarishestvo Neftyanogo Proizvodstva Bratyev Nobel—in English, The Brothers Nobel Paraffin Production Company (aka Branobel).

The transformation of Baku’s oil fields into a capitalist production sector had begun in 1872 with the auction of 15 blocks in the Balakhani oil field and two blocks in Bibi-Heybat, according to a history prepared by Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Energy in 2020.

This drove a 340% growth in oil production between 1876 and 1882, from 24,000 to 816,000 tons, respectively, between those years. By 1894 Azerbaijan’s production equaled that of the US (5.55 million tons per year) though Baku’s fields were 20 times less productive, according to Branobel archivists.

Other Branobel firsts as recounted in the company archive include:

- The world’s first oil tanker, the steel-hulled Zoroaster, commissioned in 1877 transported Baku’s oil to European and Asian markets via the Baltic Sea and the Russian river system.

- First railway transport with tank wagons to deliver oil across the Russian Empire.

- First attempts to produce Caspian oil offshore.

- First diesel-powered ships. Russia’s Vandal and Sarmat river barges delivered oil and oil products from Azerbaijan to the empire’s domestic market.

How Mr. Diesel Commercialized His Engine Using Baku’s Heavy Oil

As the story goes, a Swedish employee of the Nobel Company in Russia had seen an early version of Rudolf Diesel’s invention at an annual meeting of German engineers in the late 1890s. Back home in St. Petersburg, the employee, Anton Carlsund, suggested that Emanuel Nobel acquire the patent. Nobel ran Branobel after his father Ludvig Nobel died in 1888.

German experts had contested Diesel’s patent, asking if engines could be run at the high pressure envisioned. As Nobel and Diesel negotiated, a suggestion was made to experiment with heavy oils—likely made by Nobel when he realized the implications for his St. Petersburg factory and the heavy oil produced in Baku.

Quoting from the Branobel archive: “On February 16, 1898, Emanuel Nobel signed the contract with Diesel, paying 800,000 Marks. “The cool Swede is now more on fire than me for my engine,” Rudolf Diesel wrote to his wife. Of the 800,000 Marks, 600,000 was paid in cash and 200,000 Marks for shares in the newly established Russische Dieselmotor Co., Nürnberg.

This first engine was a 20-hp vertical engine with an A-shaped stand and with a crosshead connection to the connection rod and crank shaft. The machine was tested officially at the Technical Institute in St. Petersburg.

During this period of heavy industrialization, the Nobel brothers were hardly alone. The Rothschild’s Banking House in Paris had registered the Caspian Black Sea Co. in 1883 focused mainly on exporting Azerbaijan’s oil and oil products. The family’s banking structures loaned money to build the Transcaucasus Railway linking Baku with the Georgian Black Sea port of Batumi in 1883. They also financed construction of oil tank wagons.

As a result, the Rothschilds became the leading exporter of Russian kerosene by the end of the 1880s, Mir-Yusif Mir-Babayev, a professor at Azerbaijan Technical University in Baku, wrote in the spring 2018 edition of Visions of Azerbaijan magazine.

Their petroleum concession in Baku was so large that it quickly became the chief competitor of John D. Rockefeller’s company, Standard Oil, before they sold out their oil interests in 1912, according to the Rothschild family archive.

The nascent Royal Dutch Shell and Shell Transport and Trading companies cooperated with the Rothschilds and Nobels to further expand Russian crude and kerosene exports from the Absheron Peninsula, particularly to Asia, and further cut into Standard Oil’s monopoly.

World War, Civil War, Revolution, and Lenin’s NEP

The growth Azerbaijan’s oil industry experienced in the 19th century, war and ideology destroyed in the early 20th. Between the disruptions of World War I, the Russian Revolution, and civil war across the empire, Azerbaijan’s contribution to world production had by 1920 fallen to 15% while during the same period, US production was in first place globally.

The nascent Soviet Union needed help and so as Lenin unveiled his New Economic Policy (NEP), the virtues of profit were written into the Marxist vernacular and oil concessions were offered to foreign companies to draw investment, foreign workers, and the latest technologies to Baku.

One deal the Soviets struck in 1923 was with the International Barnsdall Corp., a US-based engineering firm, which brought “dozens of American engineers and technicians” to Baku while “introducing new technologies such as rotary drills necessary for the drilling of larger and deeper wells,” Jonathan H. Sicotte wrote in his dissertation.

A review of academic research on the NEP era concludes that the Barnsdall deal was less of a concession and more of a foreshadowing of Soviet trade practices to barter oil for western technology and training while retaining control of the assets. Royal Dutch Shell, whose assets in Baku had been nationalized, and Sinclair Oil negotiated for what would have been true oil concessions and near monopoly control of production. The Soviets said “no.”

Eventually Stalin would take the “go it alone” approach to building the USSR’s oil and gas industry in isolation. And so it went until the Soviet Union itself collapsed at the end of 1991.

Azerbaijan had declared its independence 4 months earlier in August 1991 after the failed coup in Moscow. It then endured its own political chaos, social upheaval, and a war with Armenia until Heydar Aliyev, a veteran of the KGB and the Soviet Politburo, took control in 1993 in a military coup of Azerbaijan’s own.

After centuries of having served the interests of three empires in succession—Persian, Russian, and Soviet—Azerbaijan was finally free to leverage its oil and gas largesse to its own benefit. As the Cold War ended, Baku pivoted to Turkey and set its sights west to Europe.

Back in the USSR, Azerbaijan Launches the Global Offshore Industry

Among the many firsts that Azerbaijan’s oil industry can claim, the one that most shaped the country’s future, not to mention the future of the global oil industry itself, was the discovery in 1949 of the Neft Dashlari (Azerbaijani for Oil Rocks) oil field.

An article in the September 2022 issue of the AAPG Explorer noted that at the time of its discovery, “Oil Rocks was considered the world’s largest offshore oil field, both in terms of reservoir volume and recoverable oil reserves.”

The Soviets designed special marine vessels to produce in open water up to 100 km offshore and built over the years from 1947 to 1949 Oil Rocks City—the world’s first offshore oil platform seated on wooden piles driven into the seabed, and decommissioned ships that were sunk to create artificial islands (another first in the industry).

Still producing, Oil Rocks supplies 70% of Azerbaijan’s domestic oil and gas demand, according to SOCAR. The historic Neft Dashlari complex is being joined to a new gas-processing platform fed by a subsea well in 500-km-deep water as part of today’s Absheron gas and gas condensate offshore project in which TotalEnergies and SOCAR each hold 35% stakes after ADNOC’s 30% farm-in a year ago.

The Soviet Union employed directional drilling at Neft Dashlari first before its use spread throughout the Caspian and to west Siberia. “Baku oilmen accelerated the process of development of the offshore fields by applying scientifically based schemes of artificial methods of maintaining (reservoir) pressure by flooding and other techniques,” SOCAR’s Vice President for Geology, Geophysics and Oil and Gas Field Development, Khoshbakht Yusifzade, wrote in Azerbaijan International’s Summer 1996 issue.

In a way, the Oil Rocks discovery wasn’t a surprise considering that first oil had technically flowed there 150 years earlier, but the technology needed to sustain production, let alone commercialize it, would take several generations to mature.

Scientists Knew Something Was Happening, They Just Didn’t Know What

In 1803, a Baku merchant, Haji Kasimbey Mansurbekov, produced oil from what is said to have been the world’s first offshore wells—two wells dug 18 m (59 ft) and 30 m (98 ft) from the coast in the bay off Bibi-Heybat village. In 1825 a storm destroyed the wells, and the merchant abandoned the project.

As of 1859, scientists had begun to study the area, curious about the black oily film that covered rocks in the shallows offshore Baku. In 1896 mining engineer and early pioneer in offshore oil production, Witold Zglenitsky, asked the Baku Mining Department to drill on land reclaimed in Bibi-Heybat Bay.

The Mining Department refused Zglenitsky’s project, however. His concept envisioned building a waterproof platform 4 m above sea level to enable oil to load into 200,000-ton (1.4 million‑bbl)-capacity barges in case of a gusher, the AAPG Explorer article detailed.

A land reclamation project followed in 1924 in hope of producing the field around Bibi‑Heybat Bay, and a decade later, mining engineer F. Rustambekov proposed methods to develop the Azerbaijan shelf at six potential exploration sites.

The “Contract of the Century” Kicks Off the Great Caspian Oil Sweepstakes of the 1990s

The dissolution of the USSR freed Azerbaijan of its colonial chains, giving it free reign to leverage its oil and gas wealth to its own benefit.

The most consequential event for post-Soviet Azerbaijan was the signing in September 1994 of the “Contract of the Century” which brought on a feeding frenzy among energy majors eager to pay hefty signing bonuses to obtain production sharing agreements (PSAs) to explore and hopefully produce any of a host of blocks that were put on auction at the time.

A consortium of 11 foreign oil companies from six countries together with SOCAR signed the PSA to develop the Azeri, Chirag, and Deepwater Gunashli oil fields (ACG): the US, UK, Russia, Norway, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia, plus a “who’s who” of global majors: BP, Amoco, Exxon, Unocal, Statoil, and Lukoil.

Most of the other PSAs signed at this time failed as exploration drillers hit only dry holes or identified reserves that were insufficient or too complex to be declared commercial.

But ACG prospered, developed by the BP-led Azerbaijan International Operating Company (AIOC). Production peaked at 835,100 B/D in 2010, as described in OTC 25870 which details how engineers addressed geohazards unique to the area while planning the project’s development through 2015.

In the first decade after contract signing, AIOC upgraded an existing platform, installed seven new fixed platforms and three subsea well manifolds, laid approximately 1200 km of subsea in-field and pipelines to the Sangachal export terminal onshore, while drilling more than 160 appraisal and production wells, the paper’s authors noted.

In April 2024, BP as operator, produced first oil from its $6-billion Azeri Central East (ACE) facility as the nearly 30-year-old ACG development entered a new phase.

ACE is historic in that it represents ACG’s first new production since the 2014 startup of the West Chirag platform, but most significantly, the ACE production facility is the first BP-operated offshore platform controlled from onshore, in this case, from the Sangachal export terminal.

Oil production is down at ACG with average daily oil production having fallen to 363,000 B/D in 2023 from 415,400 in 2022. Bakhtiyar Aslanbayli, BP vice president for the Caspian region, communications and external affairs, told Russia’s Interfax news service in February that SOCAR is addressing the decline issue.

In an interview in March with the German website Caucasus Watch, John Roberts, a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center, suggested that while “the output of BP’s ACG is half of what it used to be,” gas exports could fill “some of this vacuum” because “condensate can be fed into oil pipelines to export as oil.”

Shah Deniz, Absheron, Gas, and Renewables—Formula for the Future

We turn now to the high-pressure Shah Deniz gas condensate field, BP’s largest-ever gas find, operated from two platforms in the Caspian Sea under a PSA signed in June 1996 that has since been extended to 2048.

BP holds an operating interest of 29.99% in Shah Deniz with partners including Turkey’s TPAO (19.0%), the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) (21.02%), Russia’s LUKOIL (19.99%), and the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) (10.0%).

The start of first gas from Shah Deniz’s Alpha platform in 2007 put Azerbaijan literally on the map as a gas exporter, with a capability to deliver gas to Georgia and Turkey via the South Caucasus Pipeline.

But the startup of Shah Deniz Phase 2 (Bravo platform) in 2018 topped up a whole new list of superlatives including: first subsea development in the Caspian Sea; largest subsea infrastructure operated by BP worldwide; and the point from which the 3500-km SGC pipeline network begins its journey to deliver Caspian gas to Europe.

In his interview in March, the Atlantic Council’s John Roberts raised doubts as to whether Azerbaijan could boost gas production enough to fill the SGC’s planned 10 Bcm per year capacity, noting that his own calculations suggest “we are not likely to see more than 5 Bcm per year added to Azerbaijani supply over the next 4 years or so.”

Azerbaijan says it is on track to fulfil an agreement to significantly boost its exports to the EU between now and 2027.

So how to plug that 5 Bcm per year gap? Why not reduce domestic consumption which, Roberts said, “brings us to renewables” and the question of whether Azerbaijan can tap into enough offshore wind power (and solar) to make more natural gas available for export.

The World Bank estimates that Azerbaijan could be producing 7 GW of power from Caspian Sea winds by 2040, and Baku is lining up partners to take the challenge seriously.

- Saudi-listed ACWA Power and SOCAR agreed in April 2024 to partner on green hydrogen production. ACWA is currently building a $345-million, 240-MW wind power plant in Azerbaijan’s Absheron-Khizi regions.

- TotalEnergies signed a Memorandum of Understanding in June 2023 to develop 500 MW of renewable wind, solar energies, and energy storage systems for Baku’s national grid.

- BP expects a final investment decision (FID) by year-end on the $200-million, 240-MW Shafag solar power plant situated near Jabrayil.

- In 2023, SOCAR partnered with Masdar, the UAE’s clean energy company, to develop three major solar and wind projects in Azerbaijan with a combined capacity of 1GW.

- SOCAR also agreed with Masdar and ACWA Power to develop 500 MW of renewable energy in the Nakhchivan region of Azerbaijan.

- ACWA is also eyeing construction of a 1-GW onshore wind power plant, a 1.5-GW offshore wind power plant, and various hydrogen projects in Azerbaijan.

So, have hydrocarbons had their day in the “Land of Fire” which conceived the modern oil and gas industry 2 centuries ago? Hardly.

While Equinor may be selling its Azerbaijani assets, the UAE, which hosted COP28 and now passes the gavel to Azerbaijan, has picked up a 30% stake in the Absheron gas and condensate field. Hungary’s state-owned energy conglomerate MVM is buying a 5% stake in Shah Deniz gas, building on its 2020 purchases of Chevron’s stakes in BP’s ACG oil project and the BTC (Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan) export pipeline.

Azerbaijan’s Trend news agency reports that SOCAR, TotalEnergies, and ADNOC will decide by year-end 2024 or early 2025 on declaring FID on Phase 2 of the Absheron gas project, which would raise production to 5.5 Bcm per year for export to Europe.

Absheron Phase 1 went onstream in September 2023 with 1.5 Bcm per year that is currently sold on Azerbaijan’s domestic market.

For Further Reading

The Pivotal Role of Azerbaijan Oil and Baku by J. Bahramov and H. Hasanov, A.A. Bakikhanov History Institute.

Baku: Violence, Identity and Oil, 1905–1927 by Jonathan H. Sicotte. Dissertation.

Royal Dutch Shell: A Brief History by Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum.

The Rothschild Pages of Azerbaijan’s Oil History.

The Rothschild Archive’s Website.

OTC 25870 ACG Field Geohazards Management: Unwinding the Past, Securing the Future by A.W. Hill and G.A. Wood, BP America, et al.

SPE 177400 Understanding a Complex Overburden To Deliver Safe and Productive Wells at the Giant Shah Deniz Gas-Condensate Field, Offshore Azerbaijan by G.R. Price, D. Hall, and K. Kaiser, et al., BP Exploration (Caspian Sea) Ltd.

SPE 219287 Fault Pattern and Structure Configuration of Absheron Sill, South Caspian Basin, New Insight From High-Quality OBN Seismic by X. Dengyi, L. Rouis, and L. Xiaoliang, et al.

Discovering Lost History in the Ashes of the Soviet Collapse

It was American Thanksgiving 1992 and less than a year after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. William Courtney had arrived as the first US Ambassador to the newly independent state of Kazakhstan.

He decided to host Thanksgiving dinner and invite the entire American community in Almaty—all 20 of us—or were we fewer? Let’s just say we all fitted around one rather large oval table at what was then the best hotel in Kazakhstan—the communist party hotel.

The new chef was a Texan from San Antonio, and he did his best to transform chickens from the local market and a sort of red berry sauce that passed for cranberry into a meal fit for pilgrims. Afterall, that’s what we were, pilgrims who had journeyed long distances to some sacred place.

The conversation was riveting—journalists, entrepreneurs, diplomats, adventurers, all children of the Cold War crystal balling the future.

I was in town as both journalist and entrepreneur hoping to launch a business news service on behalf of a so-called investor (with no money) who had recruited three gullible freelance journalists—including myself—from Kiev in Ukraine.

After covering Ukraine’s independence vote, wading in the Dnieper River, skirting the roadblock at the entrance to Chernobyl while living in a communal apartment on Karl Marx Street in downtown Kiev, Kazakhstan sounded exotic if not foreboding.

But back to Thanksgiving dinner 1992 in Almaty.

Ambassador Courtney and US Deputy Chief of Mission Jackson McDonald bantered about how global politics might be reordered in the wake of the Soviet collapse and one comment has stuck with me to this day some 30 years later—pay attention, they told us, to where the Caspian and Central Asian states might pivot.

They were right, and while Kazakhstan pivoted in multiple directions—Russia, China and the West—to balance those three behemoths; Azerbaijan turned to Turkey, a natural fit culturally and linguistically, that has positioned Baku as a supplier of oil and gas to Europe.

On my first trip to Baku in 1994 I didn’t just smell the crude oil in the air, I could taste it as the taxi (always a Soviet Fiat-style Lada with no meter) sped through the Bibi-Heybat oil fields enroute from the airport and a moonscape with rusty pump jacks pumping came into focus.

To the right, were red tiled roofs of what looked like houses in a suburban subdivision you might find in Europe or North America—an odd sight considering the usual Soviet grey block architecture everywhere else.

Though it might have been an urban myth, the driver explained that the houses had been built for foreign managers who produced the fields before the Russian Revolution.

Ahead as we approached the outskirts of Baku was the Ateshgah fire temple built in the 17th and 18th Centuries for Hindu, Sikh, and Zoroastrian worship. The secret of their god of fire: natural gas which the Soviets piped in after natural seeps stopped flowing in the 1960s—having a fire temple was still good for tourism.

I was one of a dedicated group of energy journalists who visited Baku while on the Caspian exhibition circuit which included Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan around the time that Azerbaijan’s President Heydar Aliyev announced “The Contract of the Century” with a literal “Who’s Who” of international partners at that first major oil and gas exhibition in Baku.

The PSA between Azerbaijan’s state oil company SOCAR and a consortium of 11 foreign oil companies from six countries aimed to develop the Azeri, Chirag, and Deepwater Gunashli oil fields (ACG) in Azerbaijan’s sector of the Caspian Sea.

On the Sidelines of History, We Did Have Our Fun

While today’s HSE managers would faint at the thought, we once talked a Soviet helicopter pilot to take us out over the Caspian to buzz the production platform at the ACG project area.

The rusty chopper in desperate need of a new paint job stayed airborne miraculously as we strained against our seatbelts when a crew member threw open the side door and the pilot banked to give us a clear view as he circled the platform. One disappointment: we failed to get permission to land—I wonder why?

In Baku the newly built Hyatt was the only “real” hotel in terms of most tastes but only The Wall Street Journal or CNN could afford it and those of us with the trade media were often freelancers without a travel budget.

I stayed on the 14th floor of the Absheron—a Soviet disaster area overlooking Independence Square where riots and a massacre had occurred 4 years earlier.

The Absheron had a secret. With ownership of everything up for grabs everywhere in the post-Soviet world, the Absheron had been divided between its employees who controlled individual floors like private fiefdoms.

The fellow who created the profit center on the 14th floor knew how to please foreigners on meager budgets. He tidied things up, did some painting and most importantly replaced the burned-out light bulbs. He bought new curtains and hired an English-speaking receptionist, aka the cashier, who took only hard currency and only in cash.

As for recreation, who needed a tour guide? Ask any enterprising driver out to make a few bucks with a dilapidated Lada and you would be whisked around for an afternoon to visit the Dashgil mud volcanos and marvel at Paleolithic petroglyphs at nearby Gobustan.

Note: My foot (and leg with it) slipped into one of those mud volcanos once and thankfully my cab hire acted before the rest of me followed. A more scientific exploration of the inner workings of Azerbaijan’s mud volcanos can be found here.

Finally, let’s not forget the Yanar Dag 10-meter-long wall of fire that has been erupting from methane seeps for decades outside of Baku. Another enterprising entrepreneur opened a café a safe distance across from the flames where modern day fire worshipers sip tea while contemplating the methane emitting natural wonder.

It will be a different world when international guests gather in Baku for COP29 to plan the next industrial revolution 30 years after Azerbaijan rose like a phoenix from the ashes of the Soviet collapse. There will be fun but it will be far tamer.

For Further Reading

OTC 15120 Seismic Interpretation and Classification of Mud Volcanoes of the South Caspian Basin, Offshore Azerbaijan by M.Z. Yusiifov, P.D. Rabinowitz, Texas A&M University.