The key to governing a late-life oil province like the North Sea is getting the balance right between initiatives to maximize recovery in late-life assets with the practicalities of planning for decommissioning. Fail on the first and oil is left in the ground that could have generated tax revenues. Fail on the second and decommissioning costs far more than necessary with the UK government covering roughly half of the cost. This is the challenge that the UK’s Oil and Gas Regulatory Authority is wrestling with.

An example of the planning challenge is the capacity of onshore yards in the UK for deconstruction work. Between 2017 and 2040, Westwood anticipates the removal of 261 fixed platforms in the UK, equating to 2.6 million tons. This will require a large amount of onshore infrastructure to ensure that projects are not delayed, potentially causing cost overruns or the use of yards outside of the UK with availability.

With the recent removal and subsequent delivery of the 24,000-tonne Brent Delta platform to a yard in Hartlepool and award of a deconstruction contract for the Buchan Alpha FPSS to Veolia’s Dales Voe facility in Scotland, the decommissioning industry in the UK is now very visibly underway—making open, industrywide, discussions vital.

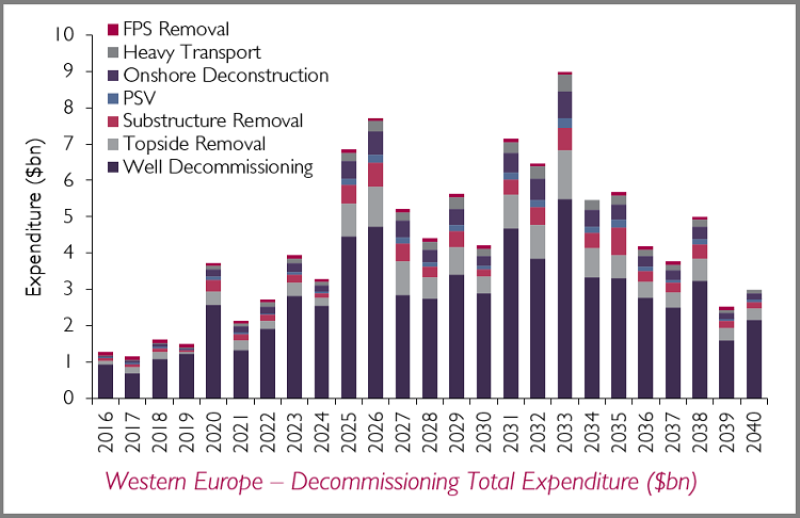

The mindset towards decommissioning is changing for the better with many operators setting up dedicated departments, and indeed several political parties making references to it in their recent UK election manifestos—a far cry from 2015, when decommissioning was not mentioned at all. The UK government will be liable for around half of the bill – equating to an estimated USD 28 billion between 2017 and 2040. Thus, they need to be actively involved in ensuring that overall costs are minimized while the value of decommissioning to the UK in contract awards and job creation is maximized.

On this they share a philosophy with operators with the managing director of Repsol stating that they were “pleased the decommissioning phase (of Buchan Alpha) will create further sustained value for the UK supply chain and additional employment.” This echoed sentiment at a recent East of England Energy Group event where representatives of Shell and Centrica confirmed that they planned to use UK yards wherever possible for decommissioning of platforms in the UK.

Time pressures for the building of new yards have been reduced somewhat, however, as the UK offshore sector has been more resilient than expected. Many fields that were forecast to be abandoned in the current price environment have continued to produce as OPEX costs offshore UK have fallen dramatically. The latest edition of Douglas Westwood’s World Offshore Maintenance, Modifications & Operations report forecasts that prices in 2017 are expected to be 25% lower than at peak in 2014. As a result, Westwood forecast that the majority of “decom” expenditure will come after 2025—providing enough time for the continued development of decommissioning yards across the UK.

Ensuring that the UK has the capacity for decommissioning will likely require government support, especially in the next few years where the business case for new yards will be weaker. The UK has already seen some commitment with the Scottish Government announcing a GBP 5 million Decommissioning Challenge Fund, specifically to ensure that the supply chain in Scotland benefits from decommissioning—including support for infrastructure upgrades and the developing of business cases for new yards. Following this, several party manifestos called for a deepwater port to be built specifically for decommissioning, demonstrating a commitment to ensuring that the UK maximizes the value of decommissioning to the UK economy.

The article was originally published on Douglas Westwood’s Westwood Insights. Reproduced with permission.