Halliburton’s acquisition of South Carolina-based startup Ometric earlier this decade was notable for a couple of reasons.

First, it represented an emerging trend of the oil and gas industry seeking out, modifying, and applying technologies from other industries. Second, it resulted in perhaps the only instance where dog food tech was applied to oil and gas operations.

Charged with nurturing a broad-minded approach to innovation within Halliburton has been Greg Powers, who has served as the oilfield service firm’s vice president of technology since 2010. Trained as a chemical engineer, he spent the first 30 years of his career working at companies such as GE, DuPont, and United Technologies. Halliburton brought him aboard for that reason.

Powers has since hired a new technology head for each of Halliburton’s 14 business units—all but two of whom came from outside the industry—including former colleagues from his previous employers, which he considers “companies of very high rigor” that place “a really big emphasis on innovation” and assure their products work reliably, attributes he wanted to emulate at Halliburton.

During 2010–14, Halliburton hired 2,000 people, the majority of whom were from outside of oil and gas and held master’s degrees or PhDs. Responding to complaints that he wasn’t hiring enough domain knowledge, Powers explained that “when you hire smart people who come from other industries, they bring a lot of new ideas. The [oil and gas] industry, as I viewed it, was stultified—I mean insulated and not very progressive.”

Halliburton requires its senior technical personnel to attend meetings of societies outside the industry such as the American Institute of Chemical Engineers, American Society of Mechanical Engineers, and Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

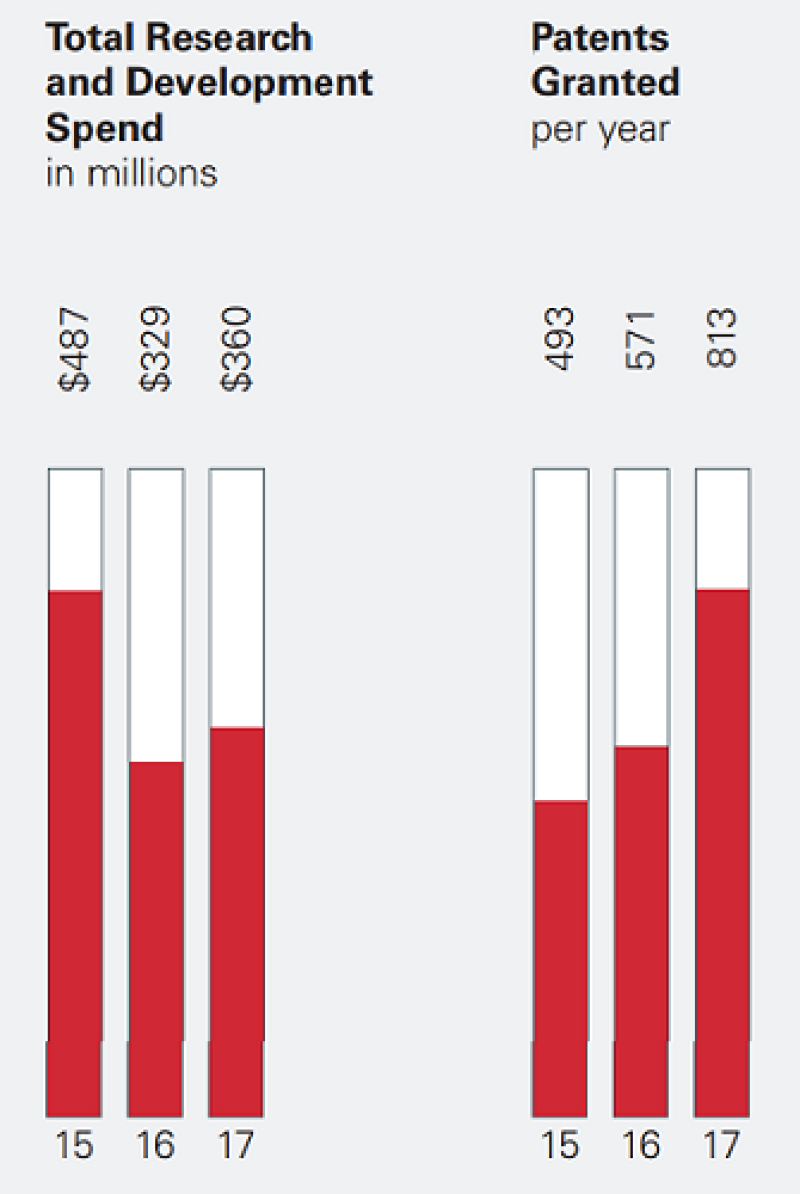

Results of the company’s internal transformation, he said, can be seen through the number of patents it has racked up in recent years. Its patent rate, a primary measure the company uses to gauge its progress in technological development, spiked 400% by the end of 2017 with 813 patents granted during the year, according to its sustainability report. That amounts to 1.4 patents granted for every $1 million spent on research and development.

“You’re talking about thousands of people who have to have this attitude and this belief that if we see something, no matter where it is, and we think it has value in our value proposition—lower the cost and increase productivity—we can try to make it relevant,” Powers said. He noted, however, that making technology from other industries relevant to the oil and gas industry requires time, effort, and millions of dollars on Halliburton’s behalf.

Prior to the addition of Ometric, Halliburton was looking for an expedited way of performing downhole fluid analysis, hoping to measure, in real-time, the constituents seeping from the reservoir at in-situ conditions right after a well was drilled. Commonly used samplers had been adept at determining the collectability of a downhole sample, but the operator would have to send those samples off to a lab and wait 2–3 months for thorough analysis.

Ometric had been spectroscopically measuring impurities in dog food using multivariate optical computing (MOC). Halliburton built on Ometric’s MOC approach to chemical analysis in 2013 by commercializing ICE Core, an integrated computational element service that uses more-versatile photometric detection inside the downhole sampler instead of laboratory spectroscopy and its accompanying bulky equipment.

With ICE Core, an optical sensor acts like a processing chip, performing analysis on fluid constituents inside the well. This results in immediate, more-complete information about the constituents present and fluid identification as the tool samples the reservoir.

In an example where hiring outside of oil and gas benefitted Halliburton, a polymer industry veteran developed a method of waterproofing resin for use in a well’s secondary annular barrier, a well integrity structural safeguard that was required after the 2010 Macondo well blowout. The company believed that adding resin to cement instead of using just base cement would provide a solution with better mechanical properties that’s adaptable to unique environments.

“In about a year and a half, we went from no polymer barriers to the beginnings of what’s now a huge suite of polymers mixed with cement, where we can tailor the thermal coefficient of expansion” along with “the brittleness and the flexibility” of those barriers, Powers said.

The company has also taken technology from the US Navy’s submarine program and applied it to its wireline business with its Acoustic Conformance Xaminer service, an acoustic analysis tool that detects, measures, and characterizes leaks and flow in or around the wellbore and behind pipe. This enables prevention of larger, problem leaks from occurring down the road.

“Different kinds of leaks make different kinds of sounds, and we’ve learned the ‘language of the whales’ so to speak—except it’s the language of leaks,” Powers said.