Realism and Pragmatism Have Indeed Won the Day

The narrative of our industry has recently shifted quite radically, leading to ebullient enthusiasm, optimism, revival, and, yes, even a sense of deserved vindication. The reasons behind these tailwind feelings were:

- Geopolitical volatility is reshaping international relations, trade, supply chains, and economic growth scenarios. This naturally affects energy demand expectations and hydrocarbon futures.

- The US is currently causing this volatility. In another aspect of its “exceptionalism,” with just over 4% of the world’s population, it produces about 20% of the world’s oil and 25% of its natural gas, contributes almost 13% of the world’s gross domestic product, and emits 14% of its greenhouse gases (GHG). The recent about-face in US trade and energy policies, including walking away from the UN Climate Change Conference and the Paris Agreement and mandating its oil and gas industry to “drill, baby, drill” had disruptive effects.

- Several European international oil companies had vowed to aggressively evolve into clean energy companies to the detriment of their hydrocarbon portfolios. Some have had to backtrack under shareholder pressure because their returns shrunk.

- As Daniel Yergin has observed, the energy transition is “troubled,” not delivering in required investment, results, and timing. A sobering rendezvous with reality challenges the feasibility of the aspirational “net-zero emissions by 2050” scenario, which is today looking more like a compass than an itinerary.

- Paradoxically, the artificial intelligence (AI) revolution that might help us reengineer our energy systems requires the mushrooming of huge data centers with an insatiable hunger for energy and cooling water. For example, their demand for power has been growing at a compound annual growth rate of 18% in the US and, according to the International Energy Agency, could treble globally in the next 5 years.

- While solar and wind reached record output in 2024, so did oil, gas, and even coal. As long as population and economies grow and compound on one another, energy demand will relentlessly grow, despite achievements in better energy efficiency.

- Energy security and affordability thus are outweighing sustainability, destabilizing the trilemma’s inherently challenging balancing act. We are not experiencing a transformative transition; it is more about addition than replacement. In fact, the word “transition” implies a radically different final state, while the ongoing process looks more like an evolution.

This Reality Check Was Necessary, but Is It sufficient?

Naturally, those upbeat oil and gas feelings became somewhat tempered when the US disrupted global trade, thus affecting global economic growth expectations. Consequently, oil prices immediately dropped below breakeven in some basins.

But, in any case, a reality check seemed overdue. Nonetheless, we must consider if “necessary” implies “sufficient.” Climate change will surely continue its acceleration spiral because it is indifferent to politics and electoral swings. So, this leads to the question: “And now what?”

Many respectable energy pundits bet their chips on ours being the quintessential innovation species, with an incredible history of finding cooperative solutions to a wide variety of complex problems, such as transporting huge stones over long distances to build tombs and sanctuaries, containing plagues and diseases, reducing poverty and hunger, and closing holes in the ozone layer. And now we have an incredibly powerful and shiny new wrench in our toolbox, AI.

AI is proving to be an enabler and catalyst of innovation and technological development, not only for chemistry, physics, and biology, but also for energy and mining. It has the potential to make our industry better by enhancing seismic interpretation and integrated modeling and improving exploration, development, drilling, completion, production, refining, and marketing.

Surely it also will enable the acceleration of the energy transition by progressing energy efficiencies; fast-tracking the technological development of renewable energy generation and storage; streamlining entangled supply chains; optimizing infrastructure and grid design, operation and integration; and helping decarbonize hard-to-abate industries (e.g., steel and other building materials; building heating, cooling, and maintenance; navigation; and package delivery).

While this may be true, these contributions, while valuable, remain partial. And, in any case, projecting our past innovation prowess and assuring ourselves that “we will figure it out somehow” provides scant comfort.

Why Hold the Course?

Our industry has been commendably responding to societal demands to mitigate climate change (and remain socially and commercially sustainable), by combining in varied degrees what we like to call the Three D’s: “Decarbonization” of its operations, processes and facilities; “Diversification” of its energy portfolios with renewable energies; and enabling these with a “Digital Transformation” (Fig. 1).

The following are strong reasons for mandating our industry to hold this evolutionary course:

- A record $1.2 trillion was invested globally on energy transition technologies in 2024 (39% just in China). This was 40% more than investment in oil and gas.

- The US elects a new administration every 4 years.

- An extended environment for lower oil prices, if it takes hold, provides an opportunity to invest in the Three D’s during a time of lower opportunity cost.

- The incorporation of climate and transition risks into credit ratings affects our cost of capital, particularly debt via medium- and long-term bonds.

- Regarding equity capital, many large institutional investors and asset managers will continue to include environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations in their decisions (albeit perhaps tempered by substandard returns). Short-term, and in line with the current zeitgeist driven by the geopolitical disruption, ESG priorities may be eased for a while, but climate and social risks will not just go away. Despite creating cumbersome burdens for companies, mandates for consistent and comparable sustainability reporting may continue to take hold.

- The emergence of globally compatible carbon pricing schemes (e.g., cap and trade) and regulations restricting or taxing GHG emissions will continue to evolve.

- It may take just a couple of climate-driven disasters to reenergize social demands, increase policy risks, and augment the threats to our operating and social licenses.

- Oil and gas investors accept our industry’s idiosyncratic risks (commodity price volatility, geopolitical, geological, operational, socioenvironmental, regulatory, and political) because they are rewarded with higher returns. But what if we eventually reach peak hydrocarbon demand and our returns converge with those offered by renewable energies?

Models for Transformation

There is, naturally, a continuum on how different companies have been engaging in the Three D’s. Given the differing levels of enthusiasm displayed by some players, and because quite often climate debates resemble religious disputes, we have tried a classification via the following religiosity metaphor (with all due respect):

- Nominal Believers—They may be dragged to church on Christmas and Easter. They are true to their hydrocarbon roots but are evaluating emissions, implementing small operational improvements, and perhaps experimenting with a renewable energy pilot because it seems a prudent or strategic thing to do.

- Churchgoers—They attend services weekly. This class represents most of our member companies. They are keeping focus on their legacy hydrocarbon businesses but are actively seeking opportunities for decarbonization. They are modifying operations to reduce venting and flaring, monitoring, measuring, and eliminating methane leaks, and electrifying prime movers. Some are divesting from mature, marginal, or heavy-oil assets and attempting partial portfolio shifts to renewable energies (in more substantial scale than just pilots). Some are beginning to consider embedding decarbonization in decision-making and investment.

- Ordained Ministers—They have consecrated themselves to the transition. These European giants sacrificed their hydrocarbons at the altar by committing to harvesting existing reserves only, divesting from exploration projects and greenfield developments, aggressively investing in low-carbon solutions, and fully integrating decarbonization into their decision-making.

But, as ever, capital will follow profitability and profits drive pragmatism. We may have shareholders who are activists for mitigating climate change, but we have more shareholders who are activists of dividends and capital gains. As I mentioned above, several “ordained ministers” have had to abandon the altar and the pulpit, sit back in the “churchgoer” pews, and revisit their exploration and production growth opportunities.

Perhaps some went too far in their “spiritual” enthusiasm, but falling all the way back to agnosticism would be going too far in the other pendular direction. While few of us now believe that rapid societal decarbonization will happen, slower decarbonization is still a robust social mandate. What has changed is the pace of energy transition but not its direction. Globally reaching net-zero emissions, while extremely unlikely by 2050, is still a binding destination. But we need to attack emissions, not just cancel energy sources. Reductionist solutions to problems in complex systems usually create unintended consequences, such as hindering energy security.

Decarbonization of our legacy operations, processes, and facilities is an obvious mandate. In contrast, gradual portfolio diversification with renewables is strategic, but we must acknowledge that it is not easy to transition from selling molecules to selling electrons. They are based on two vastly different business models. Extracting global raw commodities with volatile prices and inherent exploration and exploitation risks receives commensurate returns. In contrast, electron manufacturing is less risky but offers lower margins from domestic regulated prices. The required evolution in our shareholder mindset requires acceptance of this new hybrid business model.

Consequently, the prudent corporate attitude may be that of reasoning believers. This implies setting ambitious yet achievable decarbonization targets; measuring and reporting emissions transparently; embedding decarbonization into policies and culture to gain middle management and employee engagement; affecting all value chain segments (from drilling and completion to refining and retailing); shifting to lower-carbon-intensity hydrocarbon assets via divestments and acquisitions; weighting more natural gas into their portfolios; investing in carbon capture and storage/carbon capture, use, and storage/direct air capture if commercially applicable; opening refineries to biological dietary supplements; and investing in renewable energies if it makes strategic or commercial sense.

We must also communicate this better. “We reduced our net GHG emissions by 15% this past year” is a much more powerful communication statement than “we will be carbon-neutral by year 2050” (a future CEO’s problem). One of the worst mistakes that we can make is to give a very skeptical public the appearance of greenwashing or kicking the can down the road.

Once carbon credit becomes properly priced and fungible with liquidity, some companies may keep the ones that they generate, buy them from others, or invest in offset activities that are credible and verifiable. Proper carbon market pricing will be the best deterrent for another form of subtler greenwashing: when it’s cheaper to buy carbon credits than to clean up one’s act.

The Low-Hanging Fruit Is Also Urgently Needed

Of all decarbonization initiatives, the most logical and urgent are eliminating methane leaks and minimizing venting and flaring to what is essential for safety. We need to detect, measure directly and continually, and rapidly remedy leaks in valves, seals, tanks, ducts, and compressors. We must electrify where possible our operations and replace gas-driven pneumatic control valves. We do not need to wait for proper regulations, measures, and standards to address many of these.

Latin America and the Caribbean holds 8.1% of world population, produces roughly 10% of global oil and less than 5% of its gas. Despite emitting 6.9% of the world’s GHG and 5.1% of its CO2 and, furthermore, the fact that agriculture, deforestation and other land use dominating the region’s GHG emissions (not energy), the region emits 8–12% of the world’s methane (likely underestimated) and perpetrates 14% of its flare burning (which is not usually complete and some methane escapes). In brief, the region is doing disproportionally well with GHG emissions but disproportionally poorly with methane.

But we must also recognize that an estimated 40% of the region’s methane emissions are naturally occurring (e.g., wetlands, volcanos, seeps) and that, if we break down the anthropogenic 60% (e.g., livestock, industry, mining, garbage dumps, energy) our sector’s contribution is quite minor at 13% of these. Notwithstanding, our methane emissions are more easily controllable and abatable than, for example, those from livestock.

Moreover, given the fact that methane in our atmosphere is 80 times more harmful than CO2 over a 20-year period and 28 times more harmful over a 100-year period, controlling our methane emissions would make a tremendous difference in climate change mitigation. Furthermore, being a waste of a valuable product, a substantial proportion (some say about one half) of methane capture initiatives in our industry would pay for themselves; there is even a business case for doing the right thing.

Yes, We Must Proceed With Our Evolution

We must continue to supply hydrocarbons as the bedrock for energy security, but we also must continue to evolve and adapt to a global energy transition dictated by the need to mitigate climate change. The transition may be “troubled,” nonlinear, and slower than aspired to and more sensitive to supply and demand realities, complexities, uncertainties, and boundary conditions, but it is our ultimate destination because climate change proceeds undeterred.

We must be prudent, pragmatic, sensible, and sensitive both to shareholder and societal demands. We cannot preserve our social license, access opportunities, and attract talent if we don’t decarbonize, diversify, and practice and communicate effectively our socioenvironmental stewardship and robust governance (Fig. 2). We like to call this “360° Sustainability.”

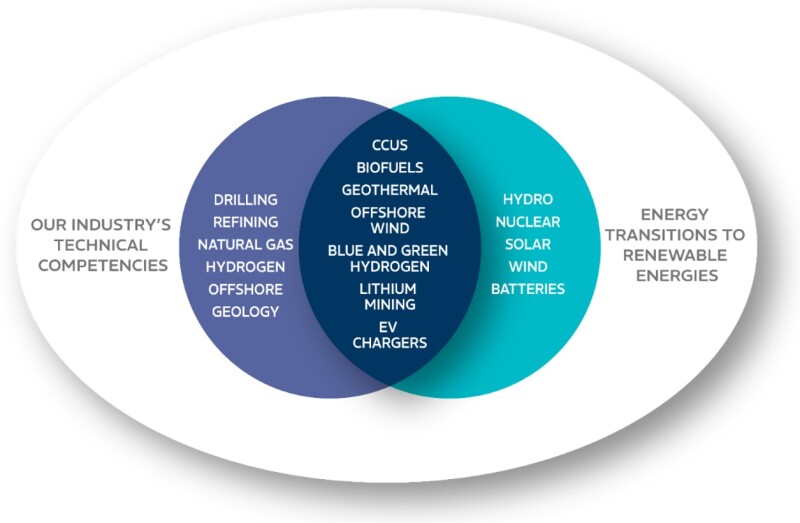

We have the technology to decarbonize our traditional businesses. Moreover, our legacy core competencies are leverageable to, for example, lithium subsurface mining, geothermal, biofuels, offshore wind, hydrogen, and retailing power to electric vehicles (EVs) (Fig. 3).

We have more than a century of technical innovation under our belt. We are veterans of resilience to price volatility, making decisions under uncertainty, dealing with heterogeneous stakeholders, and navigating geopolitical disruptions and local political cycles. We must be agents in this energy transformation endeavor. In Latin America and the Caribbean, oil and gas companies are already playing this role, focusing on producing more energy with less emissions.

This article reflects the views of Arpel’s Secretariat but does not necessarily reflect those of any of its member companies, who do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for any of its conclusions.