The oil and gas industry is coming to terms with a cyber threat landscape that has expanded beyond data breaches and the theft of intellectual property. The latest battlefront is in the field where critical drilling and production assets are at risk of being disrupted or destroyed, thanks to their highly vulnerable control systems.

The industry has experienced only a few cases of these so-called cyber-to-physical attacks but the US Department of Homeland Security predicts that by 2018 cyber attacks against oil and gas infrastructure around the world will cost almost USD 1.9 billion. One of the most dire warnings comes from the multinational risk adviser and insurance firm Willis Group, which in 2014 reported that “a major energy catastrophe, on the same scale as Piper Alpha, Phillips Pasadena, Exxon Valdez, or Deepwater Horizon, could indeed be caused by a cyber attack.” The company noted in its report that insurance providers generally will not cover such events.

The concern over control systems has come to the forefront because of the widespread use of digital oilfield technology that began about 2 decades ago. Driven by significant gains in efficiency and production, companies eagerly moved to tether nearly every facet of operational networks to the Internet, either directly or through corporate networks. On the plus side, the industry gained invaluable real-time data, various operations became automated, and engineers working in office buildings could remotely control offshore operations.

But the computer hardware that makes all of this possible was never designed to be connected to the Internet. Known collectively as Industrial Control Systems (ICS), they were built to run in isolation and thus have no security measures that guard against run-of-the-mill malware, let alone a targeted cyber attack launched by a sophisticated hacker.

“Security was not important for anyone; what was important was to have those systems operational,” said Ayman Al Issa, chief technologist and senior adviser of industrial cyber security at Booz Allen Hamilton. He added, “Based on our experience, it is easy to attack those systems—it is easy to attack thousands of them.”

Al Issa explained that the control systems are used not only in the oil and gas industry but in nearly every industry and utility sector around the world. Recent attacks on control systems in Europe prove that the digital oil field is at risk. The long list of assets using these exposed control systems includes drilling rigs, subsea wellheads, flowmeters, production facilities, pipelines, and artificial lift installations.

The industry is working on multiple fronts to address vulnerabilities, but cybersecurity experts working in the industry say it will be years before adequate safeguards are in place. Until then, oil and gas companies must face the reality that the hacker community has the advantage.

Drilling Standards Coming

Siv Hilde Houmb, chief technology officer of the oil and gas cybersecurity firm Secure-NOK, confirmed that a hacker with remote access to a rig would have little difficulty manipulating its drilling controls or the dynamic positioning systems used to keep the rig directly above a subsea well.

“Since there isn’t any protection on the control systems, it’s sort of wide open and probably the biggest challenge the industry is facing over the next 5 years,” in terms of advancing automation in the oil field, she said. “In addition to that, you have a lot of people coming and going on the helicopters, a lot of engineers with laptops that are not necessarily completely updated with antivirus and malware protection. So it’s a little messy to be honest.”

To prevent attacks, the industry is moving to secure remote connections, she said. But it is the above-mentioned scenario with employees and contractors unwittingly initiating a non-targeted attack on a rig’s network that she and other cybersecurity experts say represents the highest risk and easiest way to harm a rig. There are a few known instances that highlight how crippling these events can be.

One highly publicized case involved a newbuild rig heading from South Korea to Brazil in 2010. It is believed that malware was introduced from a worker’s laptop and then spread throughout the rig’s various networks and control systems, including the blowout preventer computer. The rig was forced to shut down for 19 days until cybersecurity personnel, who had to be flown in, repaired the networks. There are other similar reports, including a drilling rig working offshore West Africa that found itself tilting to one side after being infected with malware.

In 2013, another offshore drilling rig operating in the Gulf of Mexico lost control of its dynamic positioning systems, forcing it to shut in the well and move off station. “What happened was that various operators on that [mobile offshore drilling unit] were using the very same systems to plug in their smart phones and other devices to access other materials on the Internet, which introduced malware and that resulted in a drive off,” said Paul Zukunft, a US Coast Guard commandant admiral.

To help drillers understand the wide spectrum of risks, Houmb is serving as the Cybersecurity Subcommittee Leader (part of the Advanced Rig Technology Committee) of the International Association of Drilling Contractors (IADC), where she and a committee of nearly 50 others have created the first set of cybersecurity guidelines for drilling assets. The guidelines focus on risk assessment and are expected to be published this month after more than a year of work. Houmb said with much of the research and analysis on best practices now complete, subsequent guidelines on how drillers can build more secure networks will come sooner. As guidelines and standards become available, it will be up to individual companies to incorporate them into their operations.

Obsolete Systems

What makes control systems difficult to work with is that they were built to survive beyond 20 or 30 years, and many systems in place may have memory capacities of less than 2 MB. However, “You might find that the security solution needs 2 GB or 3 GB of memory, so you cannot bring the security solutions of today and install it in those old systems,” said Al Issa.

They are also running obsolete operating systems such as Windows XP. Microsoft stopped supporting and issuing malware patches for Windows XP in 2014, leaving it open to new attacks or even simple bugs that may cause a software failure. There are companies that will continue to provide technical support and custom security patches for Windows XP, but it is expensive and even this option brings new challenges. Replacing outdated control systems with newer ones built with more security features might seem like a good idea, but Al Issa said such a project would probably take most oil and gas companies 2 to 3 years to complete.

To work around these limitations, cybersecurity experts have proposed a number of ideas. Some are telling companies to establish cybersecurity centers to monitor performance anomalies in control system networks and detect when an unauthorized intruder might be affecting their stability. These centers could use low-cost devices called smart taps that would allow them to monitor traffic and install security devices without interrupting the control network. Another idea is to abandon off-the-shelf operating systems altogether and design specialized ones to address the unique needs of control systems.

Even as updates and patches become available for older control systems, companies must be selective in choosing which ones to accept. Cris DeWitt, a senior manager of cybersecurity engineering and analysis at the American Bureau of Shipping, said on a modern offshore drilling rig there are likely to be as many as 500 devices that manage up to 7,000 different sensors or data points. This network of systems is responsible for controlling everything from power management and propulsion to drilling and well control.

Taking the most critical systems offline every time a new software patch is released would represent a major safety risk. DeWitt explained that companies must consider if the introduction of a patch creates more problems with the system than the vulnerability it is seeking to address.

Aside from the power management systems, he added that the lack of sufficient redundancy in a typical control system does not allow for one to be taken out of service for an update. “The reason is that these systems were built to be unbelievably reliable,” he said. “We talk about rebooting our computer every week, but there are [control] systems out there that haven’t been rebooted in years.”

The Arrival of Stuxnet

In 2010, the cybersecurity community woke up to the news of a new type of malware called Stuxnet, the most sophisticated malware code ever seen at that time. Developed as a cyberweapon by the US and Israel, Stuxnet successfully disrupted Iran’s uranium enrichment program at its Natanz nuclear facility.

Stuxnet is thought to have been introduced into the nuclear facility’s network through a USB drive brought in by a worker. It then gained access to several thousand of the control systems running the enrichment centrifuges and commanded them to operate outside of their normal parameters, eventually destroying them. All the while, the displays on the operator’s computer screens showed that the centrifuges were performing normally. The malware even “phoned home” to tell its creators how it was doing.

Stuxnet has since been found to be lurking inside computer networks all across the world, including those belonging to oil and gas companies. Chevron announced that it found the malware on its systems but that it had not caused any harm. But when the code was made public, it became clear to everyone that the security technology for control systems was at least a decade behind what is used to protect corporate networks.

“The attack community paid a lot of attention to that code and learned a lot of lessons from it, and you are starting to see some of those techniques pop up in other places,” said Franklin Witter, a principal industry consultant for cybersecurity at the software analytics company SAS.

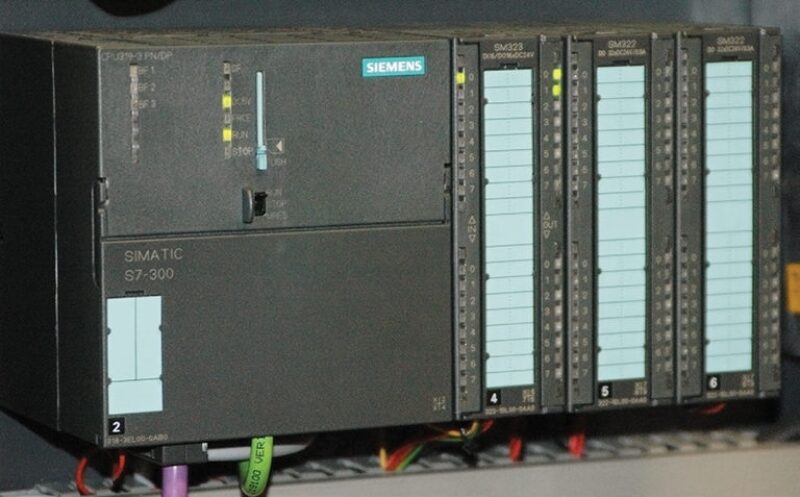

He added that with this newfound ability to infect industrial systems, hackers started a concerted research effort to understand how control systems can be manipulated. One of their most useful tools in this quest is a search engine called Shodan that lists almost every type of Internet-connected control system from traffic lights to the programmable logic controllers (PLCs) found on offshore rigs. The search engine also revealed that many control systems rely on easily defeated default passwords (e.g., 1234) and are accessible by anyone using a web browser.

While working at Symantec a couple of years ago, Witter reviewed the company’s annual war game that tested the vulnerability of control systems used in various oilfield applications. The exercise showed these control systems were using obsolete protocols no longer used in the corporate network space, he said.

“We were amazed at how little thought was put into the security of those devices,” he said. “I think there was just this assumption that these things will be put in an environment where an attacker could never get to them, and then all of a sudden people started connecting their SCADA [supervisory control and data acquisition] infrastructure and control infrastructures to the Internet, or into networks that were connected to the Internet, and not properly securing them.”

Before news of Stuxnet broke, what may be the first major control system attack caused an explosion of a crude oil pipeline owned and operated by a consortium of shareholders led by BP and the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan. The event took place in the Republic of Georgia in 2008 and was initially reported as a temporary disruption. Later, details emerged that indicated hackers gained access through an Internet connected security camera and then disabled safety measures before intentionally over-pressurizing the pipeline.

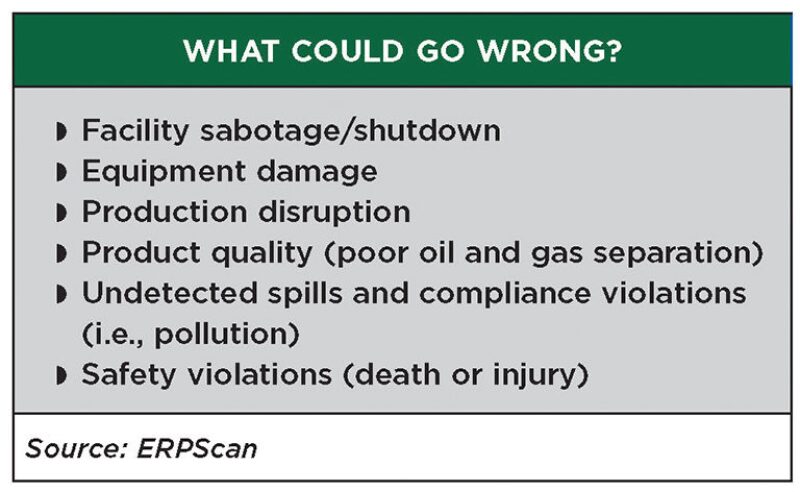

Study Reveals Risks Besides Control SystemsLast November, researchers from ERPScan, a firm specializing in SAP and Oracle systems, issued a report that analyzed risks not directly related to control systems that could disrupt an oil and gas company’s entire business. The researchers noted that 70 million B/D of oil is produced by companies using SAP technology, equivalent to about 75% of the world’s total output. Their findings focused on two specific examples of how hackers could infiltrate oilfield operations: fiscal metering and burner management systems. For burner systems, used for separation on offshore production facilities and in refineries, the researchers demonstrated how hackers could easily send operators false temperature or pressure data through an asset’s management software to cause an explosion. The metering exploits they described would allow hackers to launch a fraud attack that would involve sending out false information about the amount of oil a company is storing and transferring to a buyer. It suggested that a large enough attack would result in a global scandal and financial losses that could result in a company’s bankruptcy. “Imagine what would happen if a cyber criminal uploads a malware that dynamically changes oil stock figures for all oil and gas companies where SAP is implemented,” the researchers said. “In case of a successful attack, cyber criminals can control about 75% of total oil production.” |

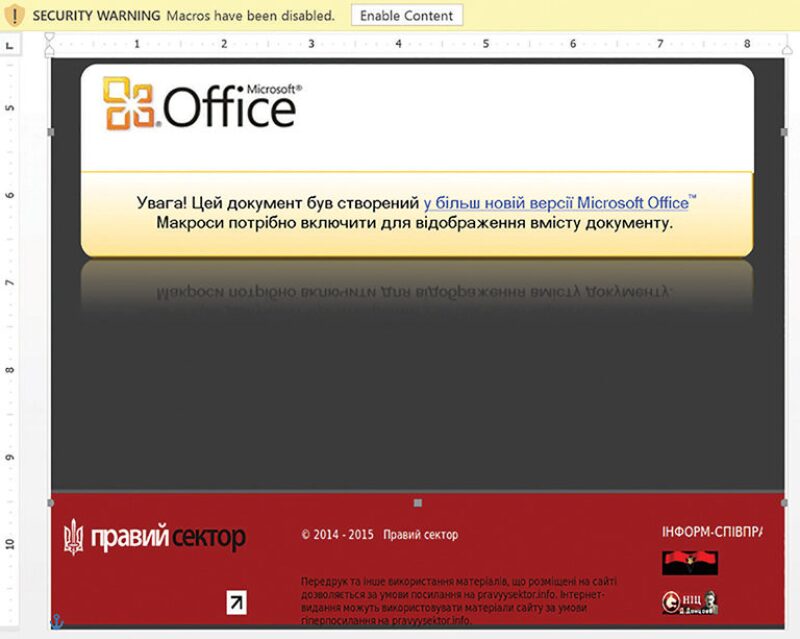

The most recent control system attack happened in December in Ukraine. Officials said a highly sophisticated attack caused a blackout that affected an estimated 800,000 people. Barak Perelman, cofounder and chief executive officer of the control system-security firm Indegy, said upstream companies should be paying close attention to the Ukraine event.

“The industrial controllers, the ones that are managing drillers, are the same industrial controllers that also manage the turbines in a refinery and generators in a power plant,” he said. “It is the same equipment, so the same hacking technology—the same malware technology—is needed in order to hack into the upstream industry.”

It is believed that the attack began when a utility employee opened an email containing a Microsoft Word file that appeared to be sent from a Ukrainian political party. The malware, named Black Energy, then moved laterally through the utility’s corporate network and into the control system and operational network. Once it found its targets, a series of ICS units used to run turbines, it allowed the hackers to cause circuit breakers to trip.

The hackers also flooded customer service phone lines using a distributed denial of service attack to delay any realization by the operators that their systems were down. Both the Georgian pipeline explosion and the Ukrainian blackout have been linked to Russian hackers who may have been acting upon the country’s geopolitical interests.

Raising Awareness

As awareness of cyber threats builds throughout the industry, major oil and gas companies are bringing more security and information technology analysts into the board room. Perelman said he has seen this change take place among his clients over the past year and that it demonstrates how executives are starting to fall into line.

“If no one in the organization is in a position that both cares about cybersecurity and can tell or ask industrial engineers to do something, then there is no way to move forward with securing the [control system] networks. It is a necessity,” he said.

Many still say that oil and gas companies need to step up efforts to work together and share information, especially regarding the threat of control system attacks. “Collaboration is a difficult problem,” said Philip Hurlston, the leader of the oil and gas special interest group at InfraGard in Houston, a not-for-profit organization funded by the US Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The group bills itself as a “partnership for protection” that opens the lines of communication between the agency and industries the government considers to be responsible for the country’s critical infrastructure.

Hurlston said oil and gas companies are reluctant to disclose cyber attacks because it would likely invite negative attention from the media, investors, and regulators. “Very little of it makes the news in terms of hearing about attacks in the industry, but these companies are constantly targeted and really do struggle to stay ahead of the game,” he said.

To encourage industry stakeholders to provide threat intelligence, InfraGard members can report attacks anonymously, which then allows the FBI to warn other companies that may suffer from the same attacks. So far, this concept appears to be taking hold. Membership in the organization’s Houston oil and gas group has grown from about 20 to almost 350 in just over 2 years and there are several other oil and gas groups across the country.

SPE Cybersecurity EffortsThis month, SPE will be hosting a symposium on Cybersecurity and Business Resilience for the Oil and Gas Industry. To be held in Dubai from 29–31 March, the symposium will address the range of cyber challenges facing oil and gas companies and how different organizations are managing their efforts. Additionally, the SPE Digital Energy Technical Section (DETS) has established a Cyber Security Committee to further the industry’s ability to protect intellectual property and assets. The committee serves as a collaborative forum for the following areas:

|