Oil companies are eagerly hiring petroleum engineering graduates, but the steep falloff in petroleum research funding is forcing a shift to alternative energy work.

On the plus side, those connected with programs said most seniors have lined up jobs well in advance of graduation and some are getting multiple offers.

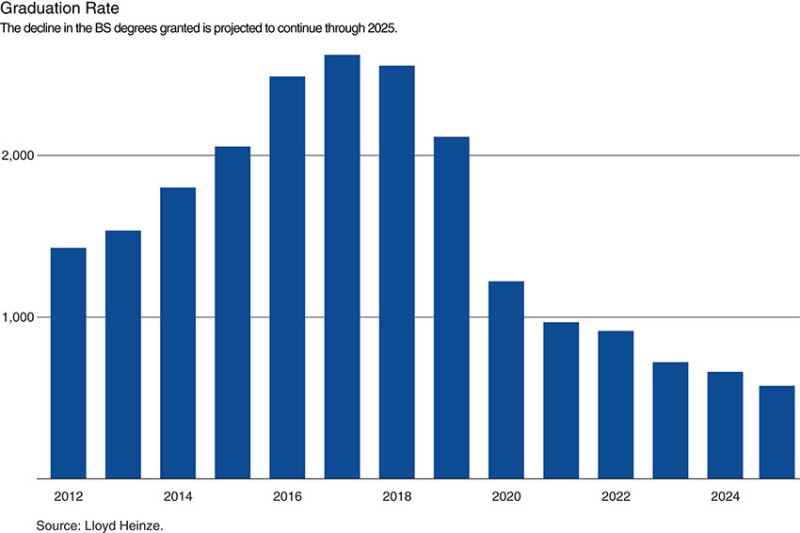

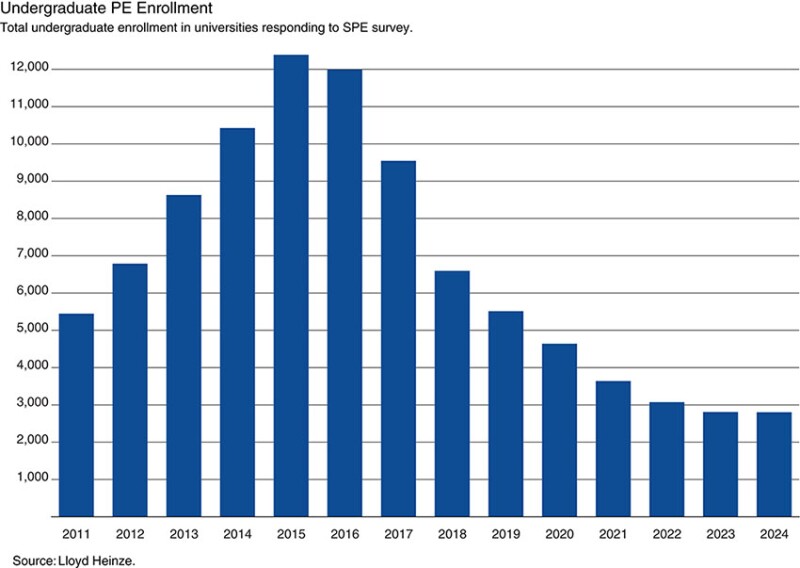

Companies are competing for a small pool of talent, with 660 seniors expected to graduate this year, down from a peak of 2,615 in 2017, according to the annual SPE survey of colleges with petroleum engineering programs by Lloyd Heinze, professor emeritus at Texas Tech, who predicts that number will drop to 572 in 2025 based on the number of juniors.

After that, enrollment looks likely to rise. There has been a 13% increase in the number of freshman and sophomore students, which is attributed to the strong demand for petroleum engineers.

“Probably word of mouth is seniors getting jobs, and junior and sophomore internships is a big factor in the rise,” Heinze said.

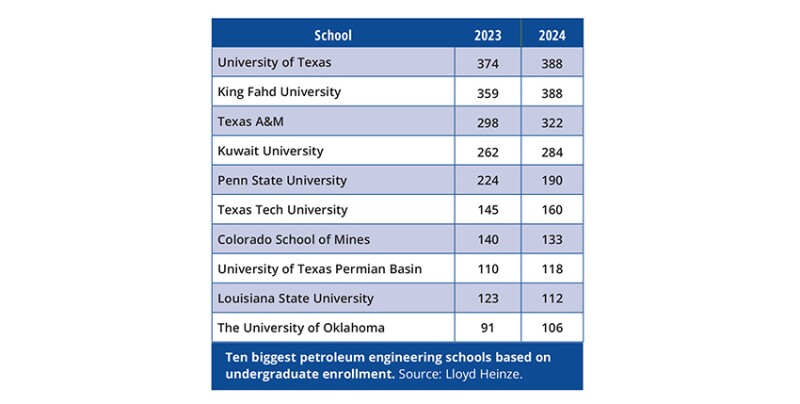

Another plus is that undergraduate enrollment is up at seven of the 10 largest programs surveyed in the US and the Middle East.

“Almost everyone is up,” said Mashhad Fahes, an associate professor at The University of Oklahoma (OU), who reports that nearly all those approaching graduation have jobs in hand, often with multiple job offers.

Internships were so widely available that OU had no takers for a summer program created to provide an alternative to paid internships a couple years back when those opportunities were scarce.

Similar evaluations of the job market were offered by sources from Texas A&M University and The University of Texas Permian Basin (UTPB). In all cases, the jobs were mostly in oil and gas exploration and production.

“They know that if they get a degree from our program, they can easily find a job in the area,” said Ahmed Kamel, an associate professor who is the department coordinator at UTPB.

UTPB, which now has more PE students than OU and LSU, draws a large percentage of its students from west Texas who have grown up around the oil business before enrolling, and Kamel said many are working in the industry while in college.

In addition to knowing the business, he said they offer another benefit: “Oil and gas companies want people from here who will stay here.”

The program, started in 2011 as part of the business school, is now part of UTPB’s College of Engineering offering degrees in mechanical, chemical, and civil engineering.

Its growth plan includes a petroleum engineering graduate program in the future, which will require increasing its research work. Kamel said that it currently has the research support it needs for teaching undergrads.

The Research Gap

Every year’s enrollment survey includes a chart showing the price of oil as of that year’s January. Heinze began doing that after the late Stephen Holditch, an influential professor from Texas A&M and 2002 SPE president, said there is a relationship between price and enrollment, and the PE survey results support that notion.

This year, the price of benchmark Brent crude has flirted with $100/bbl as oil demand has remained around 100 million B/D and OPEC+ has cut production. But in mid-November, Brent crude was trading at around $80/bbl. That is equivalent to $62 when inflation-adjusted based on the buying power of the dollar in 2014, when it last traded at $100/bbl.

The fact that companies are making money at that level is testimony to the cost cutting and technological advances made by the companies still in the business.

Industry research spending looms large because universities can no longer depend on the US government to fund oil and gas research.

“Two things are happening here,” said Johannes Alvarez, a Texas A&M graduate who serves on the university’s industry advisory committee.

The first is that the US Department of Energy stopped funding most exploration and production research unless it reduces the environmental impact of those activities and largely moved money into low-carbon energy sources and conservation.

The second is that since the price crash in 2014, research funding from oil companies is down.

While big companies like Alvarez’s employer, Chevron, have continued to support research, the number of companies backing that sort of work has shrunk due to consolidation such as the recent acquisitions of Pioneer Natural Resources by ExxonMobil, and Hess by Chevron.

Fahes is doing petroleum research aimed at explaining how low-salinity water injection can increase production in some instances. But others she works with have shifted to alternatives. For example, an OU researcher has gone from modeling asphaltene production to carbon dioxide injection analysis. Another is studying using fracturing to create geothermal heating systems.

Based on what she is seeing and hearing as a member of the SPE Education and Accreditation Committee, Fahes said a high percentage of the research done by US petroleum departments is not related to exploration and production.

Petroleum engineering faculty reported having trouble finding research funding in a recent global survey reported in a paper about how the energy transition is affecting petroleum engineering programs, for which Fahes was the lead author (SPE 215086).

On the plus side, the fact that those developing new energy sources are turning to petroleum engineering programs shows the value of drilling, fracturing, and reservoir expertise.

Fahes does not question the need for new energy sources, but fears that graduate students whose research is on alternatives to petroleum may be poorly prepared to solve oil and gas problems.

“We are feeling our identity slowly shifting,” Fahes said.

Heinze points out that roughly half of those teaching petroleum engineering are industry veterans who pass on what they have learned from experience. But, he said, finding research opportunities is a big problem for young professors looking to win tenure.

“It is not an issue writing papers, not an issue teaching; it is getting research dollars,” he said.

These universities are still home to significant oil and gas research centers. These joint-industry efforts are often built on the reputation of high‑profile professors.

Many of those are nearing retirement age, which often means the end of their research group, Fahes said.

At Texas A&M, Alvarez worked with David Schechter, a professor who ran a lab that evaluated chemicals for enhanced oil recovery (EOR).

The work related to laboratory testing methods to match chemicals with reservoir conditions was reported in Alvarez’s PhD thesis, which led to a job as an EOR and CO2 advisor for Chevron.

This year he delivered a paper on successful EOR testing in the Permian by Chevron where the EOR chemical screening method developed at Chevron was used to identify chemicals which proved effective in the field (URTeC 3870505).

A year ago, Schechter retired from Texas A&M where he’d worked for nearly 23 years. He now is the vice president of reservoir engineering for EOR ETC.

Geo-Engineering Major?

A transition to a world with a growing number of energy sources that require the expertise of petroleum engineers is likely a long-term advantage for petroleum engineering programs and prospective students worried about the future of oil companies.

But this shift to something labeled “geo-engineering” hits a hot button for many SPE members—it leads to talk about changing petroleum engineering department names.

Based on the petroleum engineering department survey, that’s coming.

While 75% of those surveyed said fossil fuels will continue to matter in the energy mix and 57% see the energy transition as a threat to petroleum engineering education, 80% see this transition as an opportunity to change things.

Those changes may well include the department’s name. Nearly half the respondents said departments should consider a name change, and “40% believe the name will change within 10 years.”

The survey showed that views on the future of oil use and the politics related to that volatile issue vary widely.

In Europe—where a rapid transition away from fossil fuels is a priority—the responses were overwhelmingly in favor of changing the name of the degree. Those in the US generally saw strong fossil fuel demand for decades ahead, reducing the need for a name change. Responses from the Middle East were in between.

In his international travels, Heinze has seen wide variations in PE education and has worked to expand the survey to reflect those.

The ranking of the top five undergraduate programs shows he has had some success in expanding the survey.

The University of Texas-Austin is followed by King Fahd University—which was number 1 last year—followed by Texas A&M and Kuwait University. But international names are limited because the survey was created to track US institutions accredited by ABET, which required enrollment reporting.

“I am hoping for a little more participation from outside the US,” Heinze said. He acknowledged that the current sample “is biased on the US programs, with a few Middle Eastern programs.”

That has long been a goal of his. Now he is working to pass that challenge on to someone else. Heinze said this is his last survey. He is working on recruiting someone to take on the job he has done since the early 1990s, when the SPE Education and Accreditation Committee discontinued publishing a book on petroleum engineering programs because of limited sales.

His immediate goal is to keep the survey going. The hard part of gathering the data is finding a person in the petroleum engineering department willing to do the digging needed to collect the data for the survey.

Longer term, he sees changes. Heinze recognizes that creating a global survey likely requires a group of SPE members with personal connections to significant training grounds in their part of the world.

Creating a consistent global survey will be a challenge. There are wide variations in programs. The US petroleum engineering model has made inroads in some parts of the world, particularly in the Middle East where many of the administrators and faculty went to school in the US. But some programs do not even use the label “petroleum engineer.”

The rationale for doing the work needed to gather education data is that it provides a leading indicator of the numbers of students and the skills sets possessed by professionals who play a critical role in the oil business and, increasingly, other sources of energy.

Fahes, who championed the energy transition survey, would like future surveys to answer other questions such as the number of women in petroleum engineering programs and how many graduate students are involved in oil and gas research.

The effort needed to track petroleum engineering programs globally would be significant, but Fahes said it could be an essential asset during a period of change.

“We need the data itself. If right now we do not watch the curve, we may be too late to fix it,” she said.

For Further Reading

SPE 215086 The Impact of the Energy Transition on Petroleum Engineering Departments: The Faculty Perspective by M. Fahes, The University of Oklahoma; R. Hosein, The University of the West Indies; and G. Zeynalov, Baku Higher Oil School, et al.

Maintaining Petroleum Engineering Education To Support the Energy Mix of the Future by M. Fahes, The University of Oklahoma; R. Hosein, The University of the West Indies; and G. Zeynalov, Baku Higher Oil School, et al., JPT.