Undergraduate education in petroleum engineering (PE) has survived the latest downturn in the industry, and enrollment has started to show an uptick in numbers. However, a different trend is evident in graduate training and academic research: the number of researchers being trained in oil and gas topics is drastically dropping.

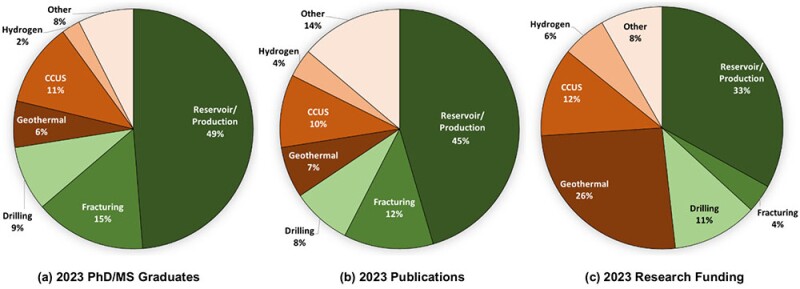

The story can be summarized in Fig. 1. Funding trends in PE departments have been shifting away from oil and gas research. These shifts require large investments in skill-building, expertise, and laboratory infrastructure, which makes it much harder to reverse the trend. Consequently, the shift may permanently alter the identity of PE departments, something that will not impact only graduate education but could alter the overall identity of these departments and the workforce they train.

The data shared in Fig. 1c shows that more than 50% of the 2023 research awards, which will fund graduate students earning degrees between 2025 and 2026, are going to be invested in geothermal, carbon management, hydrogen, emissions, and other topics that do not support improving oil and gas resource extraction.

While 73% of the 2023 MSc and PhD graduates still studied oil and gas topics around reservoir, production, fracturing, and drilling, as shown in Fig. 1a, this number is expected to drop to under 50% for 2026 graduates. Fig. 1b reveals the accelerated trend of this transition, where only 65% of the publications generated from these departments in 2023 covered oil and gas topics. Under 60% of the 2024 and 2025 graduates who published in 2023 are building expertise in oil and gas research and development.

The team collected data to study the trends over the past 10 years. It included over $137 million in external research funding and over 1,900 thesis/dissertations, in addition to over 1,100 publications in 2023. More details about these numbers can be found in SPE 220735.

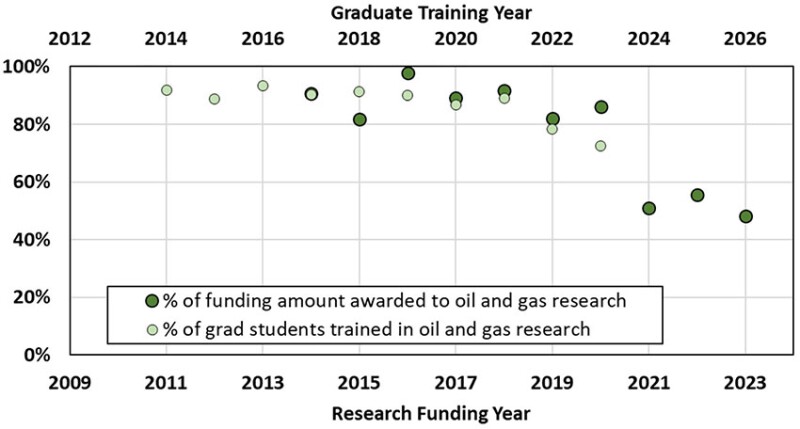

The trends in graduate training and research funding over the past 10 years are shown in Fig. 2, where the axis for graduate training is shifted by 3 years to account for the lag between the date funding was received and the graduation date for the students it supported.

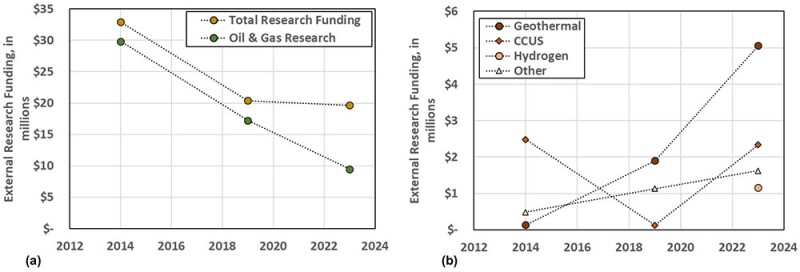

When looking at numbers rather than percentages (Fig. 3), oil and gas research funding to four of the major PE departments in the US dropped from $30 million in 2014 to under $10 million in 2023 as shown in Fig. 3a. Funding in these departments now hovers at around $20 million, where the gap was filled by transitioning to the study of sustainable geoenergy topics relating to carbon and hydrogen storage and the extraction of geothermal energy, as shown in Fig. 3b.

University Research Is Critical for Future Energy Needs

The academic community in PE departments has always been engaged in conversations, internally as well as with industry partners, regarding the future of PE education. The focus of these conversations has been mostly on the training of the PE workforce of the future. The consensus from both the academic and industry representatives has been that the growth in the use of renewable energy constitutes an energy expansion rather than an energy transition, and that there is still a need, at least for decades to come, to continue supplying a workforce trained in PE.

These conversations rarely address the dimension of graduate education and training. The absence of conversations around research and graduate education trends within industry advisory boards and academic/industry collaboration venues may be due to the misconception that undergraduate education is independent from graduate education, and that research funding is a luxury rather than a necessity.

University research is important for training the next generation of educators and industry researchers. The PhD students of today become the faculty and innovators of tomorrow. Changes in the graduate education and research landscapes in academic departments have a direct impact on the undergraduate education opportunities and on the development of the future oil and gas workforce.

Securing the Required Funding To Support PE Programs

Maintaining the PE degree requires an infusion of research funding that supports oil and gas topics in academic departments. However, there are external constraints that prevent both the government as well as the industry partners from being able to invest in that trend. While programs supported by the US Department of Energy used to fund academic research in the core oil and gas research areas in the past, the government is currently bound by Executive Order 14008 on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad, Sec. 209, Fossil Fuel Subsidies, which prevents some of the research money from funding traditional oil and gas development research.

Accordingly, one may think that if the industry needs PE degrees to be maintained for decades to come, they should be able to pick up the tab. If companies operating in the US commit even a small amount of funding each year to support oil and gas academic research, this could generate a lifeline that would allow PE departments to maintain their role in supporting the oil and gas workforce needs.

In such a scenario, geoenergy and renewable topics would still be explored by PE departments, except without the risk of abandoning and eliminating oil and gas research. This scenario, however, has its own challenges.

The oil and gas industry is also working within external constraints on where it can invest its R&D and venture capital funds. Whether it is driven by the need to hedge against the future trends in energy transition, or the need to be aligned with the wishes of stakeholders, oil and gas companies are transitioning their investments away from supporting oil and gas research as they navigate through a changing energy landscape.

PE Departments Are at a Crossroads

In a 2022 survey published in 2023 (SPE 215086), faculty reported that it is too soon to change the name of the petroleum engineering degree. The academic community has been in agreement that we need to maintain a focus on core PE education, and supplement that education with technical electives covering emerging topics such as data analytics, sustainability, and geoenergy.

However, the accelerating transition in research funding invites the need to revisit that conversation. The problem highlighted by interrogating the research numbers is not something that can be deferred much longer to wait and see how the energy expansion fares in the next 5 to 10 years.

The histories of nuclear and mining engineering present a live example of how such changing trends can have a significant impact on the industry and can at times reach a breaking point that is very hard to reverse. In 2022, nuclear technology contributed to only 4.3% of the world’s energy need, a drop from close to 9% in 2002. This decrease in the importance of nuclear technology is related to a decline in enrollment of students, aging and retirement of faculty and experts, the lack of public support and awareness, the competition with other energy sources, and the continuous changes in safety and regulatory standards (Townsend et al. 2022). The very same sentence could be said about the petroleum industry and PE education.

For universities to continue to supply the workforce needed to find, develop, and produce the increasingly more challenging oil and gas fields, they are going to need research funding. There is an evident misalignment between the messaging around the need to graduate more petroleum engineers over the next few decades, and the divestment in sustaining and funding oil and gas academic research and graduate education.

Left without any intervention, the current trend is going to have a direct impact on the topics being discussed in the classroom, as well as the future supply of faculty members trained in oil and gas topics and the supply of researchers to be hired by the research and development sector in the oil and gas industry and government laboratories.

If we truly believe that the oil and gas industry is here to stay as a significant part of the energy mix of the future, then it is critical to act now if we want to correct course. Alternatively, if we believe that what we are bracing for is an energy transition rather than an energy expansion, and that the era of fossil fuels is indeed winding down where a PE‑trained workforce does not need to be sustained beyond the next 20 years, then we seem to be on the right course that was dictated by the natural transition away from funding oil and gas research in academic petroleum engineering departments.

Takeaways

Funding for oil and gas research in PE departments has dropped by around 70% over the past 10 years. If this trend is not altered, it will have important and long-lasting impacts on the petroleum industry. The academic and industry community must discuss the impact of these trends and whether they align with the expectations around the needs over the next 3 to 4 decades. Misalignment between the trends and needs will need to be addressed by implementing strategies to sustain reliable funding for innovation, research, and training in oil and gas topics.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the various members of the Petroleum Engineering Department Heads Association (PEDHA) and the academic community that contributed time and effort in collecting and sharing the relevant data that made this work possible. We also appreciate the role of SPE and, in particular, the SPE Education and Accreditation Committee (EAC), the planning committee for the “Petroleum Engineering SPE/PEDHA Workshop: Fueling the Future: Petroleum Engineering Industry/Education in a New Era,” and especially SPE staff Mahesh Jayaraman and Tamela Claborn for their support.

For any questions or comments regarding this article, please contact Mashhad Fahes at mashhad.fahes@ou.edu.

For Further Reading

SPE 220735 Trends in Academic Research and Graduate Education in Petroleum Engineering Programs by M. Fahes, The University of Oklahoma; E.W. Al-Shalabi, Khalifa University of Science and Technology KU; and T. Hoffman, Montana Tech.

SPE 215086 The Impact of the Energy Transition on Petroleum Engineering Departments: The Faculty Perspective by M. Fahes, The University of Oklahoma; R. Hosein, The University of West Indies; G. Zeynalov, Baku Higher Oil School; D. Karasalihovic Sedlar, University of Zagreb; M. Srivastava, Abu Dhabi National Oil Company; G.S. Swindell, Consultant; N.C. Kokkinos, International Hellenic University; and G.P. Whillhite, The University of Kansas.

World Nuclear Energy Status Report 2022.

Nuclear Engineering Workforce in the United States by L.W.Townsend, University of Tennessee; L. Brady, Nuclear Energy Institute; J. Lindegard, American Nuclear Society; H.L. Hall, University of Tennessee; E. McAndrew-Benavides, Electric Power Research Institute; and J. W. Poston, Texas A&M University. J Appl Clin Med Phys.

Mashhad Fahes is an associate professor at the Mewbourne School of Petroleum and Geological Engineering at the University of Oklahoma. She grew up in Lebanon and holds a B.Sc. degree in physics (2002) from the Lebanese University. She then transitioned to studying the application of physics in solving problems related to flow in porous media, earning a PhD degree in petroleum engineering in 2006 from Imperial College. Her current work spans research in enhanced oil recovery, interfacial science, geothermal energy extraction, academic culture, STEM education, and energy solutions.

Emad Al Shalabi is an associate chair and associate professor of petroleum engineering at Khalifa University of Science and Technology in Abu Dhabi. He holds a PhD degree in petroleum engineering from The University of Texas at Austin. His research interests are focused on EOR, geological gas storage, reservoir modeling, and AI/ML. He has coauthored more than 180 scientific papers. He serves as an executive editor for the SPE Journal and is a recipient of several regional and international SPE awards. He is a registered professional engineer in Texas, an ABET program evaluator, and a professional SPE member since 2006.

Todd Hoffman is a professor and department head for the petroleum engineering department at Montana Tech. He teaches classes on reservoir simulation, EOR, and unconventional reservoirs. Hoffman holds a BS degree in petroleum engineering from Montana Tech and MS and PhD degrees in petroleum engineering from Stanford University.

Kemal Anbarci is the general manager of Venture Capital at Chevron Technology Ventures, a position he has held since 2013. He has been with Chevron for over 30 years and held a variety of engineering, technology management, and commercial roles within the company. He sits on several portfolio company boards as observer and shareholder representative. He received his MS in operations research and MS and PhD degrees in petroleum and natural gas engineering from Pennsylvania State University and an MBA from University of California, Irvine. He holds a BS degree in petroleum engineering from Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey.

Vanessa Nuñez-López is the director of advanced remediation technologies in the Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management at the US Department of Energy. Previously, she was a research scientist at The University of Texas at Austin’s Gulf Coast Carbon Center where she served as principal investigator for several carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) projects. She was also a senior reservoir engineer at Chevron’s Energy Technology Company and an assistant professor at Universidad Central de Venezuela.

Birol Dindoruk is AADE Endowed Professor of petroleum engineering and chemical and biomolecular engineering at University of Houston. Previously he was the chief scientist of reservoir physics and the principal technical expert of reservoir engineering at Shell. He was elected as a member of the NAE for his significant theoretical and practical contributions to EOR and CO2 sequestration in 2017. He has 28 years of industrial experience, holds a BSc degree in petroleum engineering from Technical University of Istanbul, an MSc degree in petroleum engineering from The University of Alabama, a PhD in petroleum engineering and mathematics from Stanford University, and an MBA from University of Houston.