A Barents Sea research expedition at the end of May located several subsea mud volcanos that may indicate hydrocarbon source rocks.

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate (NOD) on 6 June said the EXTREME24 expedition under the direction of UiT The Arctic University of Norway using the RV Kronprins Haakon research vessel proved 10 mud volcanos in water depths of 1,440–1,575 ft in the western Barents Sea. The discovery follows last year’s finding of the Borealis mud volcano in the same general area, which was part of the Awards in Predefined Areas 2023.

Rune Mattingsdal, a geologist with NOD, took part in the expedition from 24 to 31 May.

Mud volcanoes, typically associated with gas seeps, have the potential to provide information about subsurface petroleum systems, he told the Journal of Petroleum Technology. He said gas seeps are common in the Barents Sea but only two mud volcanoes had been proven in the area until this year’s expedition.

Because of the association of hydrocarbons with mud volcanoes, he said he believes the discoveries in the Barents Sea will be interesting to the industry.

Ola Anders Skauby, NOD’s director of communication, public relations, and emergency response, said the NOD is sharing the information in the hope that others will supplement the information with their own geological knowledge to better understand the potential for finding hydrocarbons in the region.

In 1990, Haakon Mosby, the first mud volcano, was discovered in the Barents Sea, and it was not until last year that Borealis was discovered.

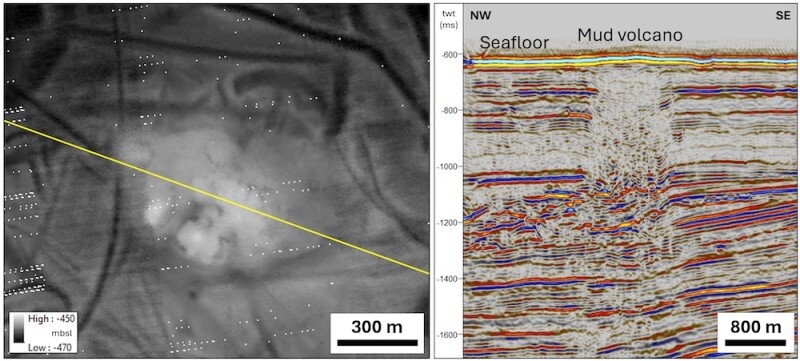

Mattingsdal called the Borealis mud volcano discovery “a bit of a surprise” but said understanding how Borealis appeared on seismic made it possible to find similar features in existing 2D and 3D seismic and then to map out other potential mud volcano locations (Fig. 1). A remotely operated vehicle (ROV) investigated the candidates and used multibeam echo sounding to verify the mud volcanoes.

Right: A seismic line through the mud volcano shows clear seismic indications of mud that comes up in a wide area under the mud volcano. The source of the mud appears to be shallow, no more than around 1,300 ft under the seabed.

There were more candidate mud volcanoes than discovered.

“We also got indications that there were more in the area of Borealis, but we were not able to explore,” he said.

A mud volcano is an accumulation of clay or other fine-grained material that has flowed out together with gas, water, and sometimes oil, either on the seabed or the Earth’s surface (Fig. 2).

“It’s a process driven by pressurized gas driving the mud up, and this mud is under-compacted compared to the overburden. That’s what’s making it possible for mud to come out to the surface at the seafloor in the case of a marine environment,” he said. “They are very widespread on land in some parts of the world.”

Mattingsdal studied onshore mud volcanoes in Azerbaijan last year, and he said those looked very similar to what the expedition saw with the ROV.

“In order to prove they are mud volcanoes, we need to show that the mud coming up is old, but we haven’t done that yet,” he said.

The ROV collected samples for geochemical and biostratigraphy testing, and preliminary results are expected in a few weeks, he added.

Geochemical test results will provide more information about the age of the mud, whether gas or other hydrocarbons are present in the sediment, and where those hydrocarbons might originate, he said. Biostratigraphy results will take more time, he said.

Next up is searching out more mud volcanoes.

“We’re pretty sure there are more out there,” Mattingsdal said.

The discovery of the mud volcanoes, taken alongside oil and gas seep studies, could indicate hydrocarbon prospectivity in the Barents Sea.

“We think there may be source rocks which are still not proven in this part of the Barents Sea, so finding mud volcanoes is a very good opportunity to get the samples needed for geochemical studies, which can tell us something about the subsurface without actually drilling into it,” he said.

He said he hopes someone in the industry finds the discovery of the mud volcanoes interesting and follows it up with their own exploration in the area.