With Europe facing winter gas shortages, North Africa’s role as an energy supplier is in the spotlight, particularly as Algeria’s 1 November closure of the Maghreb–Europe Gas Pipeline to Spain via Morocco further tightens volumes of gas that Europe can import.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects a 40% drop in Europe’s domestic gas production by 2025 outside of Norway, with the Netherlands and the UK accounting for more than 80% of that decrease.

The Netherlands is closing its Groningen field, source of almost half the country’s production in 2019 but also a cause of earthquakes. Its output will be cut by more than 50% to 3.9 Bcm in the year through October 2022, which will be the last year of regular production, according to the Dutch government. The UK cannot seem to offset declining North Sea production despite Total’s 2018 Glendronach discovery in the West of the Shetland Island area and its 2019 Glengorm discovery in the central North Sea with China’s CNOOC.

Norwegian production remains flat, averaging 120 Bcm per year over the next 5 years, the IEA reports.

And despite the energy policy voiced from Brussels that focuses mostly on renewables, few in the know dispute that gas is and will remain a critical component of the energy transition moving forward for transport, power generation, and as a feedstock to produce hydrogen.

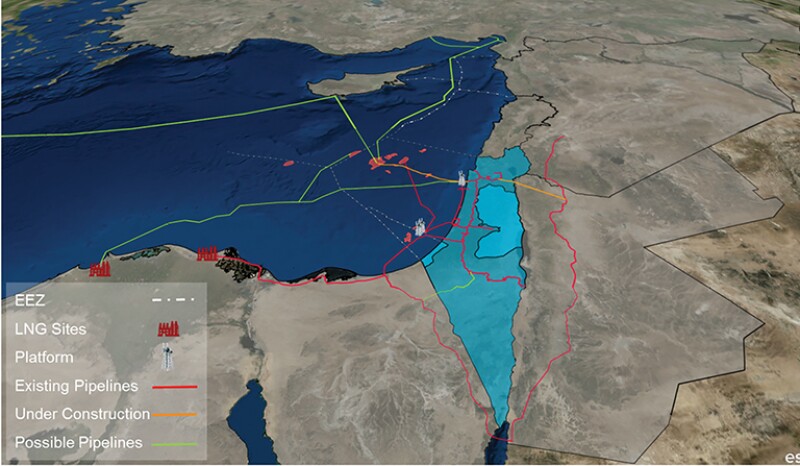

North Africa can provide gas—specifically from the Eastern Mediterranean where Egypt, Israel, Cyprus, and Greece are developing a world-class resource base while Cairo positions itself, buoyed by support from the EU and the US, as a regional hub for pipeline gas to Europe as well as LNG and electricity distribution between North Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.

North Africa’s Future Shifts From Sand to Deep Water

Eni is Egypt’s largest gas producer. The Italian major is active across the North African upstream, investing in new exploration in Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria, but its crown jewel is Egypt’s Zohr gas field in which it has a 50% operator interest and partners with Russia’s Rosneft (30%), BP (10%), and Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala Petroleum (10%).

The Zohr gas field is located in the Shorouk concession which Eni holds under a production-sharing agreement with Egypt. Situated 190 km north of Port Said, Zohr is Egypt’s largest-ever gas discovery and the largest-ever discovery in the Mediterranean Sea.

Eni brought Zohr’s gas on stream in record time, 2 years after the field’s initial discovery in 2015, according to the company’s website.

Production reached a targeted 2.7 Bcf/D in August 2019, nearly 5 months ahead of plan, due to the swift completion of eight land-based treatment units including those for sulfur removal, as well as the commissioning of three wells and a second 30-in., 216-km-long gas pipeline to join underwater production facilities to the land-based treatment plant, Eni reported.

Eni’s 2020 plan included drilling of two more production wells to boost gross capacity to 3,200 MMscf/D and the upgrading of subsea facilities and onshore treatment.

This year, Eni has also pursued an aggressive onshore exploration strategy in Egypt’s Western Desert when, at the same time, Shell has been moving out, selling its Western Desert assets in September to a consortium of independent operators.

In October, Eni announced new discoveries at its Meleiha and South West Meleiha concessions that would add more than 6,000 BOED to its gross production, according to the Italian major’s Agiba joint venture with the Egyptian General Petroleum Corp. (EGPC) that evaluates new resources.

Eni is building a new gas treatment plant to connect with Alexandria’s Western Desert Gas Complex. In the Nile Delta, Eni partners with BP.

Egypt aims to supply its own domestic gas needs while at the same time producing a gas surplus for export, both pipeline gas as well as LNG which the country currently produces at its Damietta LNG plant near Port Said at the mouth of the Suez Canal, and the Egypt Liquefied Natural Gas (ELNG) export terminal at Idku near Alexandria.

While media have focused largely on the significance of delivering East Med gas to Europe, it is worth noting that Egypt may easily offer LNG buyers in Asia attractive netback pricing considering that Cairo controls the state-owned Suez Canal Authority.

Egypt Scores LNG Export Record as Israeli Gas Flows

In October, Egypt’s LNG exports hit their highest monthly figure in 12 years according to the Middle East Economic Survey (MEES). Citing statistics from the commodity data platform Kpler (kpler.com), MEES noted that Egypt’s LNG exports had skyrocketed to 830,000 tons in October from an August low of 220,000 tons.

Egypt had announced an immediate halt in September of its own gas supplies to the ELNG export terminal and a cessation of supply by year end to the Damietta LNG plant with intent to redirect surplus gas exports to Lebanon via the Arab Gas Pipeline.

But never a vote against LNG, the move appeared to signal that Egypt is confident that gas owned by foreign partners in the deepwater Zohr field can continue to keep the country’s LNG processing facilities on track, along with the record volumes that Israel has been exporting to Egypt from the deepwater gas and gas condensate Leviathan field offshore Haifa—Israel’s largest energy project.

After demand for Leviathan gas rose an unanticipated 6% in the first half of 2021, Chevron, which has a 39.66% operating interest, moved up plans to 2022 to drill a fifth production well to boost production.

Chevron delivered first gas from Leviathan in 2019 and ramped up production in 2020 to an average of 242 MMcf/D. Leviathan and the nearby Tamar gas field also operated by Chevron (25% interest) supply 70% of Israel’s electricity. Tamar saw an average 173 MMcf/D in natural gas production in 2020.

In the downstream, Eni holds a 50% stake in the 7.56-Bcm-capacity Damietta plant as part of what it calls an “integrated development strategy” to create synergies across the value chain and build flexibility into how it manages its upstream and downstream assets.

Egyptian interests hold the remaining 50% in Damietta, which resumed operations in February after 8 years of dormancy because of an ownership dispute; meanwhile, near Alexandria and the Western Desert gas processing facility, Shell and Malaysia’s Petronas operate the ELNG export terminal with a two-train LNG production capacity of 7.2 mtpa, according to Shell. Its other partners include France’s Engie (Gas de Suez), Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company (EGAS), and the EGPC.

Desert Sun and Wind Bodes Well for North African Renewables

Eni’s value chain reaches into green energy as well. In July 2021 it signed an agreement with the Egyptian Electricity Holding Company (EEHC) and EGAS to assess possible projects to produce green hydrogen, using electricity generated from renewables, and blue hydrogen, by storing CO2 in depleted natural gas fields.

Discoveries in the East Med have brought out a synergistic spirit of cooperation among Egypt, Israel, Cyprus, and Greece. It seems to be morphing into a regional market in which Egypt will play the role of hub for the production and distribution of various different energy resources.

The EU and the US have been promoting an East Med Offshore Gas Pipeline project to channel East Med gas resources from Israel and Egypt via Cyprus to Greece and then beyond to Italy.

In October, Egypt and Greece clinched a deal to build an EU-backed EuroAfrica Interconnector subsea system of high-voltage direct current cables via Cyprus to bring renewable energy from North Africa with the first link from Egypt to Cyprus envisioned for 2022.

Given its desert conditions, North Africa is a natural fit for the development of solar power and wind facilities, something that Egypt is embracing as a core strength as it plans to leverage its own ability to produce power from renewable sources while also lining up interconnection agreements with Jordan, Libya, Sudan, and most recently, Saudi Arabia.

To the west, however, North Africa remains very much in crisis. While international companies continue to explore and support local operations, political turmoil continues to reign such as the recent political dispute between Algeria and Morocco over the western Sahara that now threatens the Iberian Peninsula with an ever-greater gas shortage than Europe is already anticipating.

The office of Algeria’s President Abdelmadjid Tebboune ordered its state oil and gas company, Sonatrach, not to renew its contract with Morocco’s Office for Electricity and Energy when it expired on 1 November.

Algeria subsequently halted gas supplies to Morocco through the Maghreb-Europe pipeline which crosses the Mediterranean into Spain at the Straits of Gibraltar. Algeria provides two-thirds of the Iberian Peninsula’s gas and will supply Spain directly through the MedGaz pipeline which enters the sea from Algerian soil.

MedGaz, however, lacks the capacity to make up for what Spain loses when one line is shut down. Algeria plans to boost capacity from the current 8 Bcm throughput that MedGaz carries annually to 10.5 Bcm.

Spain’s state-owned gas utility Enagas stated in various news reports that it has enough gas to last for 40 days and meanwhile, Algiers pledged to cover any shortfalls with LNG from Algeria’s Skikda plant.